As the retail sector becomes increasingly polarised between providing consumers with either functional or emotional shopping activities, the future of the high street will progressively be based on experiences and the personalised services generally provided by smaller stores.

Tim Greenhalgh, chairman and chief creative officer at retail and brand consultancy Fitch, explains: “The future of shopping is not retail. The future of shopping is experience. Things were already in motion here before COVID, but they’ve now been accelerated and brought to the fore.”

In his view, retail has now become transactional, whether a purchase takes place via a mobile phone, online or in store. Shopping, on the other hand, is all about service, which is being driven by several key trends. These include a growing move to buy both locally and more sustainably, and the appeal of the more human approach offered by smaller, independent shops.

The future of shopping is not retail. The future of shopping is experience

As a result, says Greenhalgh, he is already seeing evidence of big-box retail starting to follow the lead of the independent sector and embrace the idea of having a “local presence rather than just a smaller format shop in a local environment”. In other words, it is about curating and stocking local products and brands, while also “working harder to ensure staff are the face of the brand” and create ongoing relationships with their customers, he says.

“They’re starting to realise that just having shops with shelves is the old retail, while the new shopping is about service and making it real,” Greenhalgh explains.

The retail status quo, disrupted

At the same time, although many of the big brands may have been dabbling with ecommerce for a while, the pandemic has inevitably accelerated their move online, forcing them to seek new revenue streams as the usual footfall to physical stores has been curtailed.

According to Moira Clark, professor of strategic marketing at Henley Business School, this situation is opening up opportunities for smaller online retailers as supply disruption has meant consumers have bought elsewhere, liked what they’ve seen and may not go back. “COVID has been a loyalty disruptor,” she says.

But there have been other impacts too, says Connie Nam, founder and chief executive of jewellery brand Astrid & Miyu. On the one hand, for direct-to-consumer (D2C) and challenger brands, selling online was once a much cheaper option than setting up a physical store due to the cost of high street rents and business rates.

Because big brands with deeper pockets are now strengthening their presence online though, the steadily rising cost of online marketing means many smaller brands are being priced out, says Nam.

To make matters worse, Larisa Dumitru, head of ecommerce at advertising and marketing agency Ogilvy UK, points out: “What was once the playground of digitally native brands has become a more cluttered space, where everyone is trying to increase their share of audience attention.”

The impact of falling rental prices

On the other hand, high street rents are starting to fall due to a range of factors, including social distancing and chains either closing stores or going bust.

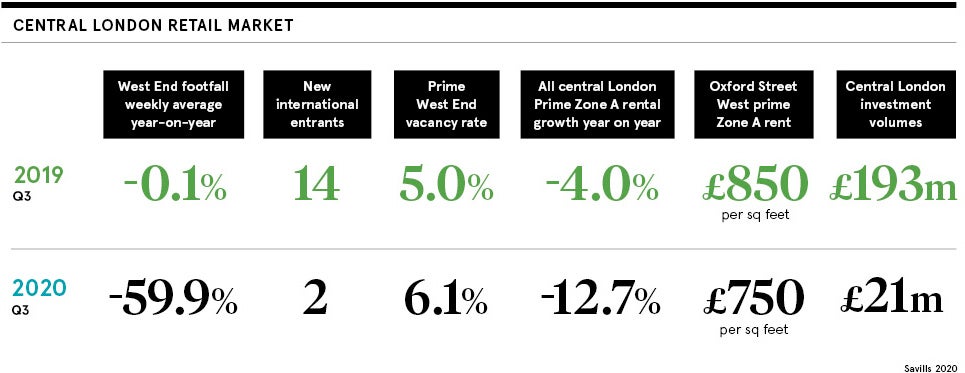

In London, for example, estate agency Savills has reported the biggest drop ever in rentals across prime central-London sites, with a 12.9 per cent fall year on year. Land Commercial Surveyors, meanwhile, forecasts post-pandemic rents could plummet by as much as 50 per cent.

As a result, Nam expects to see growing numbers of D2C and challenger brands trying their luck on the high street. While this trend is already making its presence felt in the United States, it is much more early stages in the UK. “But I can predict confidently it will happen,” she says.

“Landlords are starting to understand D2C retailers bring more traffic as we have a dedicated online following that will come to our offline store and that drives up the overall value of the street,” Nam explains.

She has just negotiated a new rental agreement with a landlord in London’s Westbourne Grove. Despite being an unaffordable location in the past, the fee is now based on turnover rather than being a traditional fixed-cost arrangement.

Creating an omnichannel experience

Dumitru likewise expects to see “more and more D2C brands testing the offline waters”. While she believes retail partnerships, such as those offered by Showfields in New York, which in a reimagining of the traditional department store enables digitally native brands to interact with customers in an offline setting for a monthly membership fee, will flourish, there could well, in the short-term at least, also be a growing appetite among D2C businesses to open high street pop-up stores.

Should they prove successful, these offline spaces could then turn into a more permanent fixture, while managing to stay true to their identity and the values that helped them grow in the first place,

says Dumitru.

A positive example of this mixed approach, she believes, is the French D2C clothing label Sézane. Its London store has a similar aesthetic to the firm’s Instagram feed, holds carefully curated stock and enables shoppers to collect their orders or return items. Dumitru describes it as “truly chic omnichannel execution”.

Other so-called experience trends include concept stores, which were first pioneered by fashion designer Mary Quant in the 1950s and the rather newer “campfire” communities, such as The People’s Supermarket in Holborn, London. The supermarket, which sells locally and ethically sourced produce, acts as a community hub staffed by volunteers who work for four hours a month in exchange for a discount on their shopping bill.

Ultimately, what this all means is, despite widespread prophecies of doom, “the high street isn’t going anywhere soon”, says Dumitru. Instead it will increasingly morph and change into a place where people interact with and experience brands rather than simply undertake a transaction. In this context: “D2C brands will enhance the high street, but there’ll also be traditional brands that will adapt and flourish too,” she concludes.

As the retail sector becomes increasingly polarised between providing consumers with either functional or emotional shopping activities, the future of the high street will progressively be based on experiences and the personalised services generally provided by smaller stores.

Tim Greenhalgh, chairman and chief creative officer at retail and brand consultancy Fitch, explains: “The future of shopping is not retail. The future of shopping is experience. Things were already in motion here before COVID, but they’ve now been accelerated and brought to the fore.”

In his view, retail has now become transactional, whether a purchase takes place via a mobile phone, online or in store. Shopping, on the other hand, is all about service, which is being driven by several key trends. These include a growing move to buy both locally and more sustainably, and the appeal of the more human approach offered by smaller, independent shops.