Getting the IT right has become fundamental to avoiding failed mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

“There are a lot more digital interactions today and therefore a lot more vulnerabilities,” says Sukand Ramachandran, partner at Boston Consulting Group.

A cautionary tale unfolded this year in banking. Between 2004 and 2013, Banco Sabadell had managed to acquire and integrate seven banks, as well as Lloyds Banking Group’s Spanish business, into its operations.

How Sabadell and TSB got it wrong

When it bought TSB from Lloyds in 2015, the UK parent bank provided a £450-million “dowry” fund to facilitate the three-year project to move TSB’s customers on to a version of Sabadell’s Proteo system. Once complete the integration was expected to save £160 million a year.

Yet on April 22 this year, following the migration of 1.3 billion records, its customers reported a host of major glitches. Online banking customers were locked out of accounts or even saw the accounts of other users. The ensuing problems cost TSB’s chief executive Paul Pester his job.

Resolving these issues has added an extra £176.4 million of post-migration costs to the TSB deal, including compensation, additional resources required, and the foregoing of income as a result of waived overdraft fees and interest charges.

TSB’s board has commissioned an independent review, to be led by Slaughter & May, to determine what went wrong, while the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) are also investigating.

In addition, the PRA, FCA and Bank of England have opened a consultation about bank IT resilience which closes on October 5. The public will certainly need reassurance about the risks that future deals pose. Although failed mergers and acquisitions are rare in the industry, there is a track record of ineffective integration.

Unilever: how to avoid failed mergers and acquisitions

In banking, as in other sectors, parties to a deal are inevitably better informed at the end of the transaction than they are at the start. Any ability to gain knowledge earlier in the process is an advantage. Once committed and with momentum building, there is the risk that stepping back seems harder than continuing.

“When Unilever acquired Alberto Culver in 2010, rather than decide on the target and then commission a big four consultancy to check their decision was a good one, which is standard practice, they started by building a performance model using third-party data to construct a rich picture of their market,” says Simon Bittlestone, chief executive of financial analytics firm Metapraxis.

“That allowed them to not only see whether Alberto Culver was the right target, but also to go out and look at 15 other targets and assess which of those might be right for acquisition.”

Taking this approach is not easy. Competitors do not share information and to build quantitative models pre-transaction requires reliable information. If a business can take the publicly available data such as financial results and apply third-party data, it is possible to build scenario planning in which the business impact of different decisions can be more easily understood, before commitments are made.

“The combination of getting the right data and the right technology to run ‘what-if’ scenarios is hugely powerful,” says Mr Bittlestone. “That also allows the business to shortcut the decision process, making calls in a shorter period of time based on real data.”

Vital to include key team members in early M&A discussions

Equally, a key to managing the operational risk of technology integration will be the point at which the technology of the other side is understood. For example, Santander tried to acquire the Williams & Glyn branch network from Lloyds Banking Group, but in 2012, when the complexity of unpicking the existing technology became too much, it had to halt the process, one of the few failed mergers and acquisitions in banking on record.

“The buyer looks at the drivers of value – revenue synergies, cost synergies, any optimisation of risk across the two books,” says Mr Ramachandran. But questions to ask include are you getting new clients or new capabilities and how robust are the new capabilities?

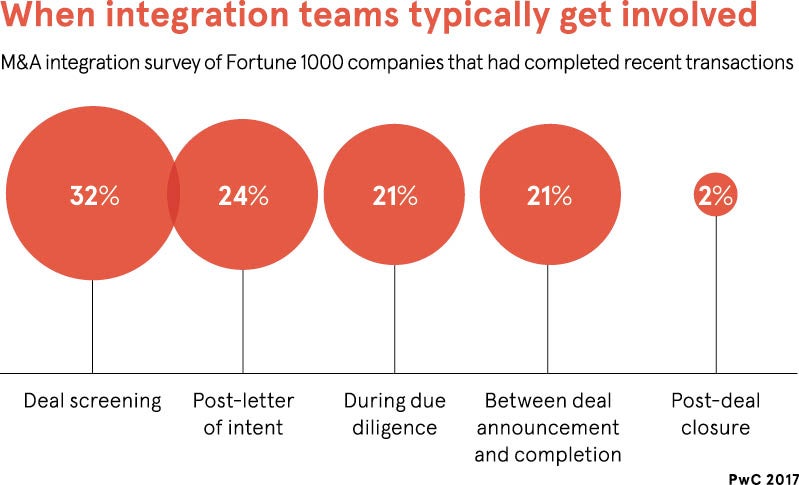

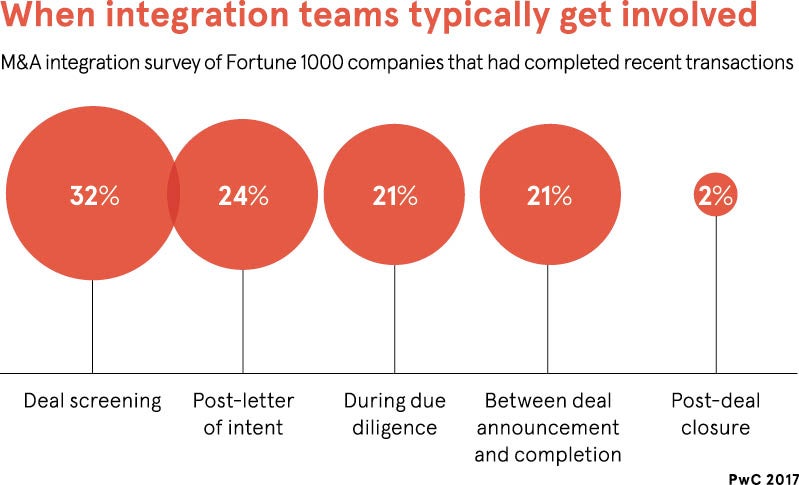

The IT team should be involved very early in M&A deals

“When an acquisition target talks to the potential buyers, they will talk more about the opportunities,” he says. “Where a platform is supporting growth, they will say what it can handle, but more often than not it will focus on customers and revenues, not systems.”

If those discussions do not involve team members with a real understanding of the systems and how they work, the bank will inevitably incur costs further down the road.

Failed mergers and acquisitions can be avoid with better testing and planning

“The IT team should be involved very early in M&A deals,” says Jan Verplancke, former global chief information officer of Standard Chartered Bank. “When we engaged in acquisitions at Standard Chartered, I was involved from day one. You have to be part of the team that goes and looks at the documents; part of that is to look at the data architecture and the systems architecture.”

Once the systems have been reviewed, the firm then has to ask which platform it will use. It may migrate one entity’s clients on to the other platform or run both platforms in parallel.

“There is the purist view of taking best-of-breed platforms then linking them up versus leaving them all and carrying duplication,” says Mr Ramachandran. “We would say neither. Find the clusters that work together and connect up the clusters. It’s like in football, you want the best sets of players in defence, midfield and attack who work together, not the best individual players thrown together. That team structure is the model for systems.”

Mr Verplanck concludes: “Maybe banks should have beta testing, as IT firms do, when they transition a group of customers with close supervisions. It would allow banks to move as fast as the customers would like without the banks becoming a target if something goes wrong.”

How Sabadell and TSB got it wrong

Unilever: how to avoid failed mergers and acquisitions