Gamified learning apps may be the face of e-learning for smartphone users in rich countries, but that is far from the extent of this powerful new trend. Countries all over the world are making the most of easy-access educational content to bolster the school experience for children who are eager to learn.

Uganda in East Africa is known for its love of tea, national parks and wildlife conservation. It is also a poor country where, according to the World Bank, the average person takes home just $170 a year. The poorest of its citizens live in vast rural areas, where obtaining an education means contending with overflowing classrooms and embattled teachers who cannot rely on the training or equipment that helps their colleagues in more developed nations.

Yet increasingly, whether sponsored by the Ugandan government, NGOs or provided by private businesses, e-learning is starting to break down these barriers.

One startup providing a successful e-learning solution in Uganda is the Walking School Bus, led by founder and chief executive Aaron Friedland. With his team, Mr Friedland has built a literacy app called SiMBi, which helps children in Uganda learn to read by providing them with recordings of students in developed countries reading out loud.

E-learning is about diminishing the gap between rich and poor by democratising the education experience

“SiMBi works like this,” he explains. “A student [in a developed country] will log on to the app and see a piece of content that they can read. They choose what they want to read, press record and start reading out loud. Later, when a student in Uganda presses play, they hear the voice and read the content simultaneously.”

The inspiration for SiMBi, Mr Friedland says, came from a family trip to Uganda during his first year of university. Initially focusing on just getting children to school via his Walking School Bus project, he was dumbfounded at the way distance served as a barrier to children’s education. It wasn’t until he got to the schools and sat through a few lessons that he realised where the real challenge lay.

“The classrooms are just not set up in a way to teach properly,” he says. “Teachers aren’t qualified to teach English, even though it’s their national language curriculum. Teachers will clap out sentences for children to repeat; you start to see huge issues in teachers’ abilities.”

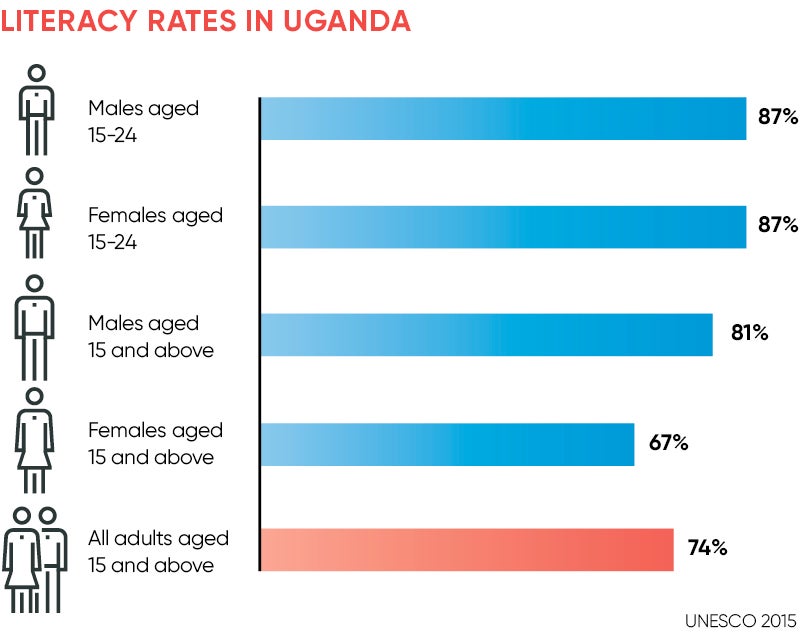

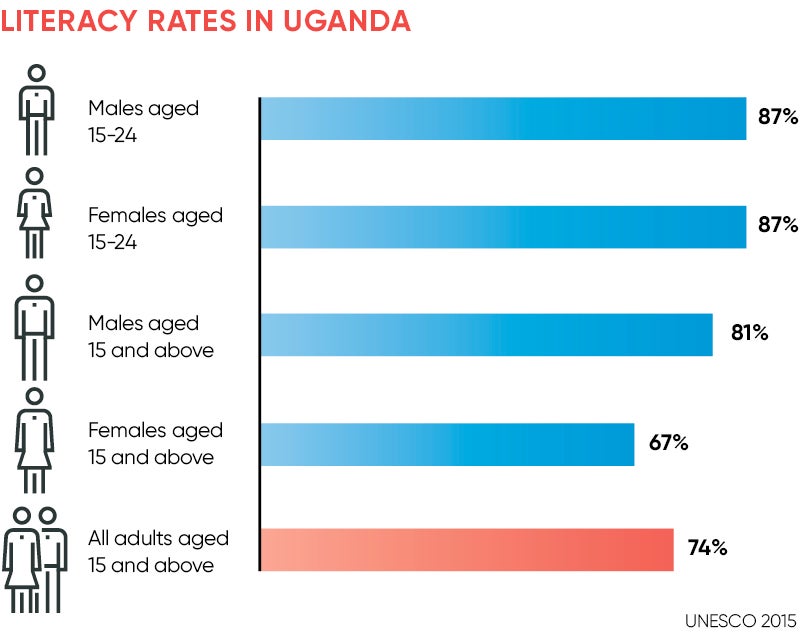

Literacy rates in Uganda are improving, but the country is not close to having a fully literate population. As of 2010, the most recent figures published by children’s rights and development agency Unicef, Uganda had a literacy rate of 73 per cent. For young Ugandans, aged between 15 and 24, this increased to 87 per cent. However, in both instances, the literacy rate for girls and women was lower than that of men and boys.

For Fabrice Musoni, an e-learning and international development specialist who has worked with Unicef in Uganda, e-learning is about diminishing the gap between rich and poor by democratising the education experience. Ms Musoni, who is based in Kampala, Uganda’s capital, says that the strides made by e-learning are beginning to challenge the way people think about education in African countries.

She says: “If you look at e-learning as democratising education, as providing access to high-quality educational content that children in the UK or in the United States have, especially in science and technology, to a child in a remote area in northern Uganda, or who lives near a refugee centre, e-learning has a massive potential to diminish the gap [between rich and poor] so students in Uganda can have access to quality educational content.”

Recently, the government of Uganda provided computers, with dedicated computer labs, to more than 1,000 state schools. Ms Musoni says that previously, without e-learning applications, these computers might have been left to gather dust. Now the trend is becoming more popular throughout the country, it is providing impetus to teachers and students to get to grips with the technology, helping build not just literacy, but also digital skills at the same time.

One challenge facing e-learning, however, is overcoming conservative views and convincing parents that the internet can be a tool for good. “One impact of e-learning,” Ms Musoni says, “has been to make people aware that technology is a tool that can be used for good. There is a lot of technophobia. Uganda is a very conservative and very religious country, so there are some subjects which are off limits.”

While Ms Musoni acknowledges that connectivity is problematic in parts of the country, the Walking School Bus overcame these problems by using Raspberry Pi micro-computers to build SiMBi classrooms.

What we understand is that literacy is the number one for academic success

Mr Friedland says: “With SiMBi classrooms, we use these micro-computers that have been pre-loaded with 64 gigabytes of educational content. The computers create their own internet servers and broadcast all of this content to all the computers in the classroom. So you’ve got students in Uganda learning from Khan Academy and all these other amazing resources.”

E-learning isn’t just helping students, either. A $2-million grant awarded by the Google Foundation to US charity RTI International is helping to provide schools and teachers with training and help in schools across the country. Sarah Pouzevara, a senior education research analyst at RTI International, explains that the tablets give teachers prompts to use lesson plans and boost the effectiveness of class activity.

However, Ms Pouzevara believes that e-learning and education still have quite some way to go before they reach levels seen in other countries. “I think for Uganda it’s still pretty far off,” she says. “They’re lucky to have chairs to sit on, desks to use. If every child gets a book, that’s already pretty good. There are huge classes and it starts to become daycare instead of a classroom.”

Still, for Mr Friedland, boosting literacy with e-learning represents the greatest possible return on investment. “I don’t like to see people doing projects with good intentions, but that aren’t particularly well thought out,” he says. “With SiMBi, we found that students using our app were becoming significantly better readers. My hope is that we can deploy holistic economic development projects that yield a very high return on investment. What we understand is that literacy is the number one for academic success.”