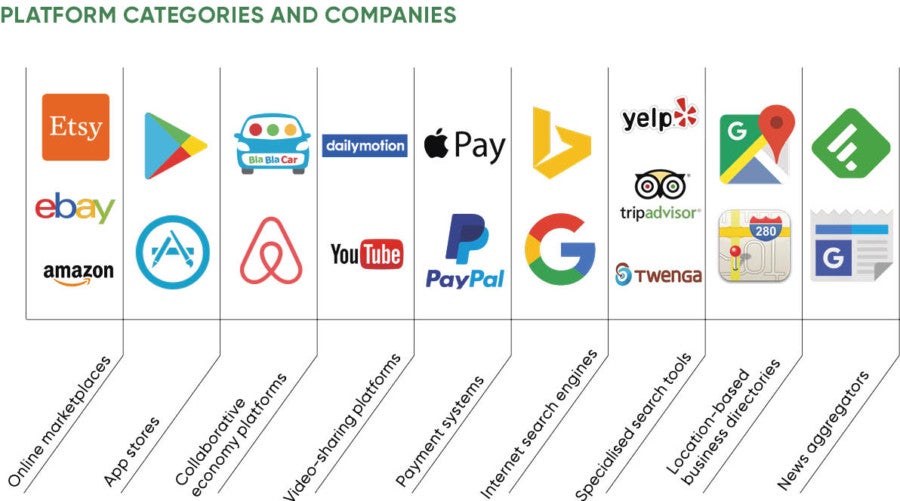

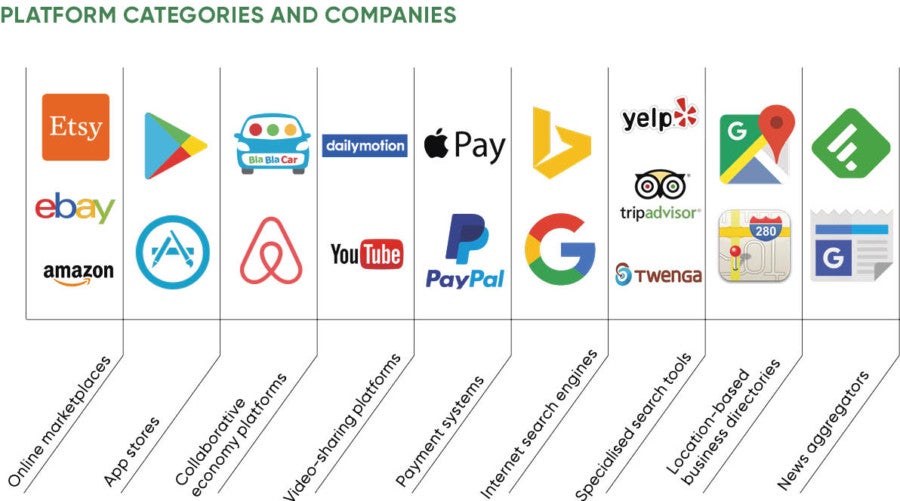

The platform economy has transformed our world in a few short years. Online marketplaces are storming market after market, connecting buyers and sellers, and taking the friction out of commerce.

With a few thumb strokes on a smartphone, a cornucopia of goods and services becomes available from Google, Amazon, iTunes and other platforms such as Uber, Airbnb and Hotels.com.

This age of the platform has changed the way businesses think about innovation. “It is really polarising once you get into this platform mentality,” says Lorenzo Wood, chief innovation officer at marketing and technology agency DigitasLBi. “We talk to clients about what they’re doing and this phrase ‘become a platform’ keeps coming up. The advantages of platforms are huge because you have lots of control, though equally you need big scale and market share and lots of service support to achieve it,” he says.

Only platforms which bring together vast numbers of providers and consumers offer massive and increasing returns on investment. The providers, from Uber drivers and hotel chains to Spotify artists and resellers, risk getting squeezed. They face massive competition on the platforms, pay a proportion of their revenue to the platform owners and are obliged to give them access to their data.

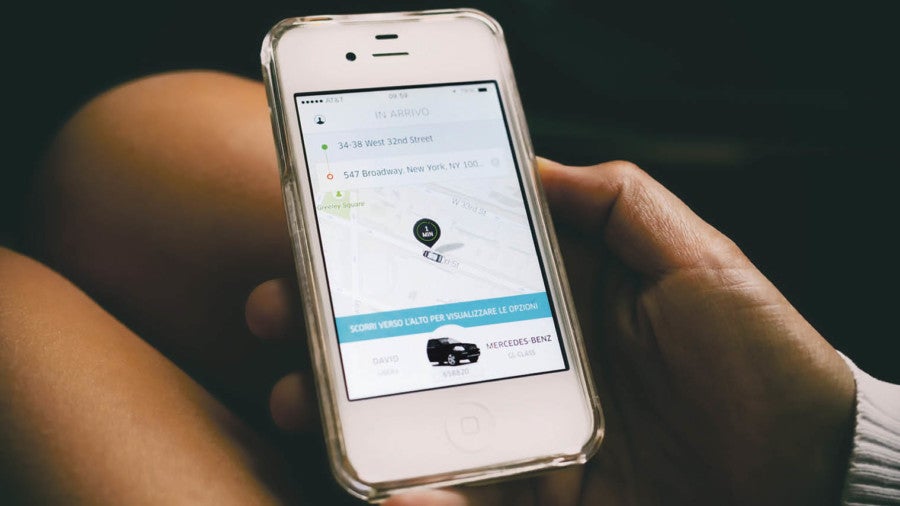

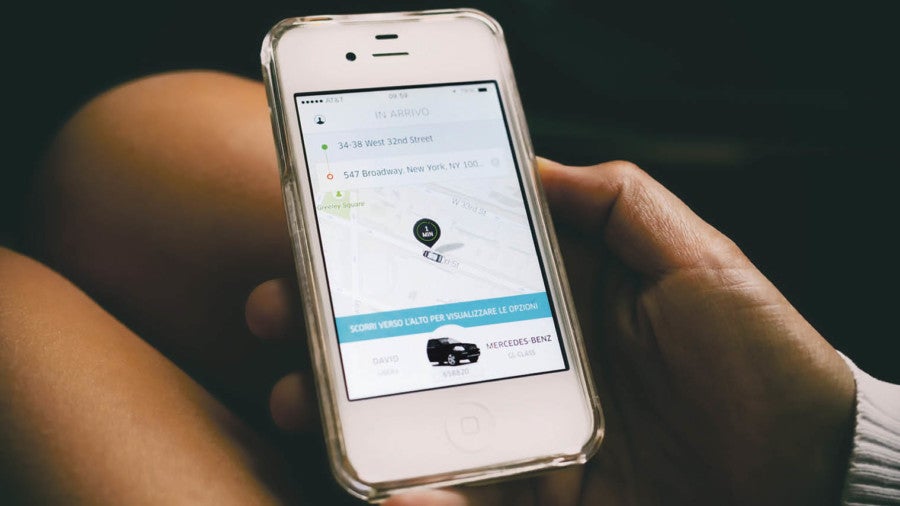

Uber is one company whose business model is dependent on the Google Maps API

But there are opportunities for those willing to work under the shadows cast by the platform giants. New eco-structures of business opportunity are being created with benefits for small and medium-sized businesses. Independent restaurants are boosting sales through home delivery platforms such as Deliveroo, while art platform Etsy connects millions of buyers with independent artists.

Hotels.com president Johan Svanstrom says that online travel agents (OTAs), such as Hotels.com, platforms which unite travelers with empty hotel rooms, bring huge benefits to both sides of the equation.

“It is clear to me that OTAs play an important role for users and partners alike, otherwise the OTAs simply wouldn’t have grown to this size. It’s value creation 101,” he says. He points to research from Phocuswright showing that OTAs such as Hotels.com contributed around $99 billion of worldwide hotel reservations in 2016.

“Any individual OTA doesn’t have more than a small minority market share globally and several large hotel companies are of a similar size. That means there will be a lot of continued competition and marketing, while investment in technology is soaring,” he says, adding that in 2016 Hotels.com parent company Expedia spent $1 billion on technology. This investment potentially benefits hotels, which can make use of innovations such as revenue management tools, guest communications platforms and flight package booking engines.

You are not a platform unless you are part of the value chain

“Market forces set the value of distribution costs on the OTA platforms, and that value is naturally related to all that reach, development and investment done by the OTAs,” says Mr Svanstrom.

“In other words, we can help to power the industry in many ways and that smarter demand generation leads to more customers for hotels. Who can argue against the win-win opportunity here?”

Meanwhile, Dominic Preston, partner in the technology group at Grant Thornton, says platforms are redefining the relationships between buyers and consumers.

But he warns that some of the mega-platforms have the capacity to dominate markets. Once they assume a powerful position, they can hike rates and further squeeze the content providers. While there may be regulatory levers against the vast size of the platforms, Mr Preston adds that “there is a kind of self-correction in the world” as executives leave these organisations to form new disruptive platforms to challenge the established giants.

GET CONNECTED

Companies need to adapt their strategies to the platform economy and make sure they are connected to as many platforms as possible. Essential ingredients of the platform economy are application programming interfaces (APIs), a type of software which allows providers to plug their services into the platforms. For instance, APIs allows Uber to plug into the Google Maps platform and enable platforms to receive online payments from customers.

Ross Mason, founder of MuleSoft which helps businesses with their APIs, says: “The way companies drive competitive advantage is not the applications that they run, but the way they can connect, compose and recompose their digital assets and capabilities into new products and services.”

He says the modern economy is based on the idea of value chains. “Instead of vertically owning everything end to end, you are now plugging in to different pieces of the value chain through APIs to deliver a new product or service to the consumer. That is critical to the platform economy because you are not a platform unless you are part of the value chain.”

Mr Mason gives the example of Atom Bank, a startup which offers mobile banking. It has worked with MuleSoft to use APIs to connect into the various steps of offering a mortgage. It can handle a mortgage application “in a matter of minutes”. This involves talking to more than 30 different systems such as credit ratings agencies, using APIs. This shows how APIs help services morph into platforms.

He says there is a winner-takes-all mentality in the platform economy: “The second player is far behind.”

Entrepreneurs creating new business models don’t necessarily need to be the next Amazon. Finding ways to plug their services into the eco-system of platforms, as Atom Bank has done, is another route to success. Simply being a provider on someone else’s platform can be positive for smaller businesses in particular. But the phrase ringing loudly in every entrepreneur’s ears these days is, “Be the platform not the product.”

GET CONNECTED