Businesses have long generated data with nearly every operation, but until recently employee behaviour was not automatically tracked.

The opportunity to improve productivity has changed practice. Using monitoring technology, companies are discovering which parts of the office work well, what times staff are active and where people congregate.

Positives

There are, of course, some substantial benefits. Workplaces may no longer have wasted space and better collaboration is possible, with data prompting the design of light, airy breakout environments. With the Health and Safety Executive noting that 45 per cent of sick days result from stress, there is also a huge potential for healthier workplaces.

Smart technology suppliers are battling to sell the latest room-monitoring cameras, heat identifiers and sensors linked to the internet of things. One company to do this is Enlightened, which attaches micro-sensors to PCs, lights and room fittings to detect motion. Meanwhile, furniture business Haworth claims sensors can inform room adjustments throughout the day to suit different teams.

Jamie Purser, category manager at Currys PC World Business, says: “Having full oversight of what’s happening across the organisation is hugely important. With more information, businesses are better able to refine and amend working practices, ensuring staff have the right set-up to work as effectively as possible.”

Office creators, such as Ohio-based BHDP Architecture, track device movement and use camera systems to play a part in design. But Brady Mick, design and change management strategist at the company, cautions strongly against applying technology alone, as it ignores “what is human about people at work”, including people’s experience, character, quality of interaction and time thinking.

“Monitors are most often used to measure use of a seat in a workplace,” he notes. “As this measurement value is quantity and not quality, it does not discern human behaviour beyond the act of sitting.”

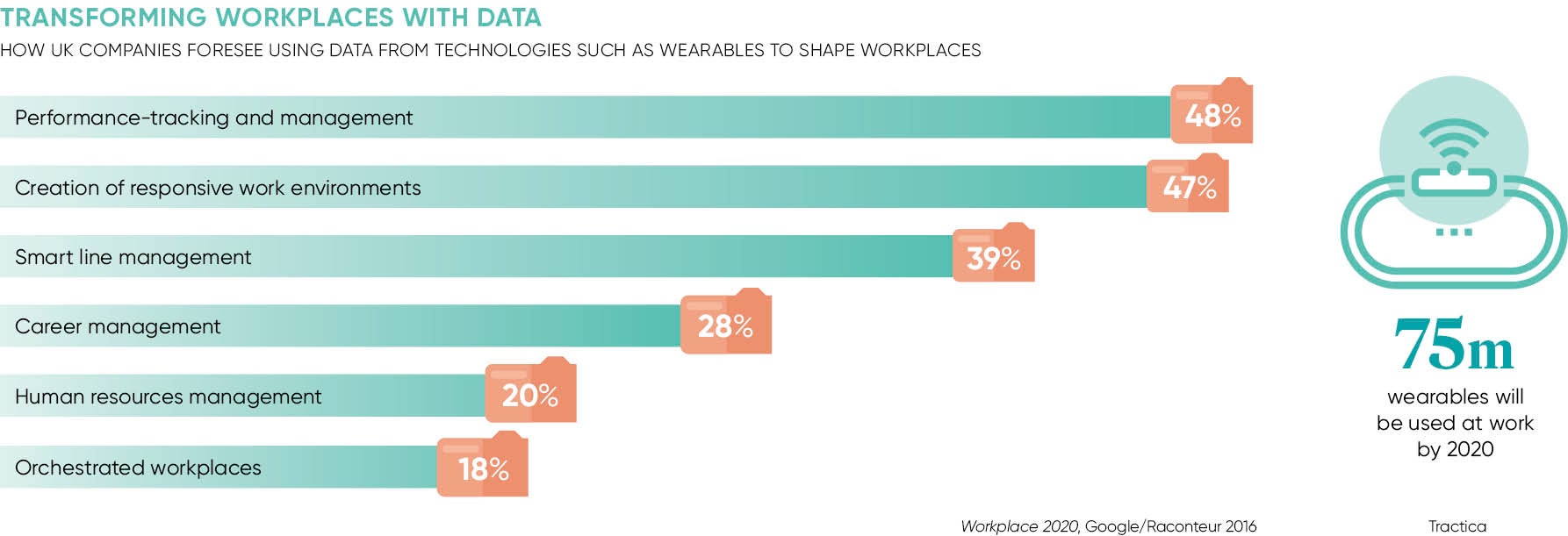

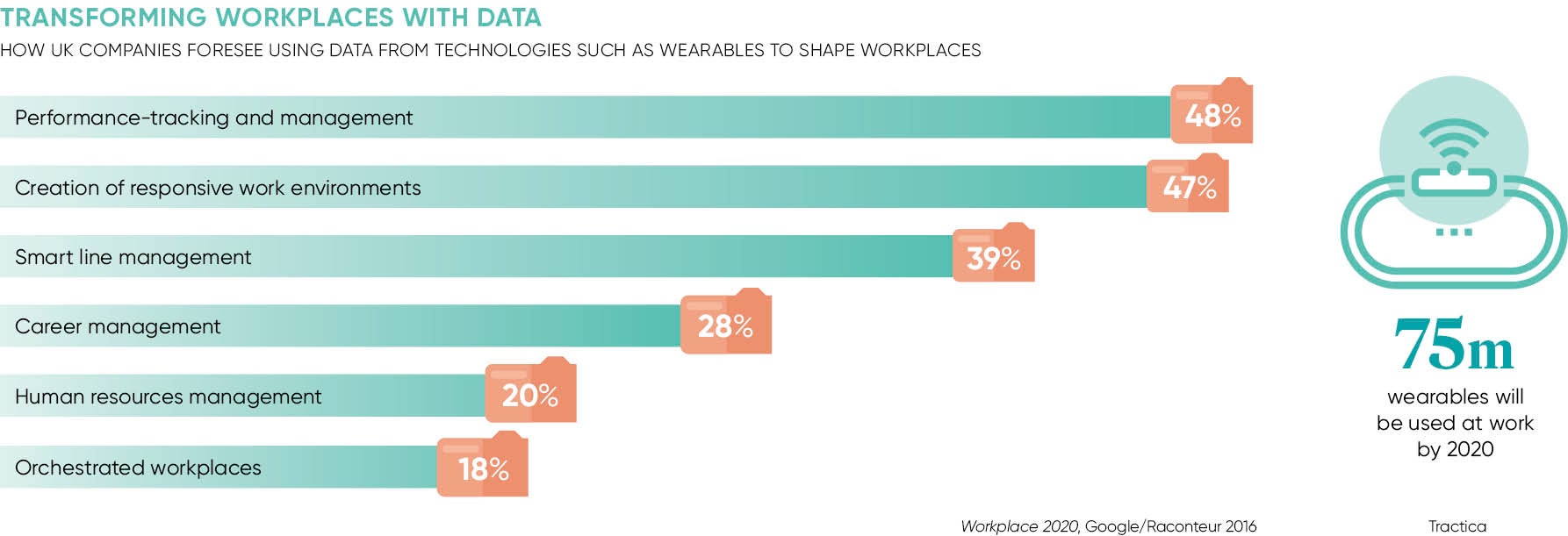

For many businesses, this knowledge gap is prompting the adoption of wearable tracking. The proliferation of consumer fit bands and smartwatches offers new opportunities here, and research firm Tractica estimates that by 2020 more than 75 million wearables will be used at work.

It is hard to imagine a manager who would not consider such monitoring to improve productivity

Some companies are even adding competition to fitness tracking, according to Mr Purser, “with staff encouraged to stay active and compete with other colleagues to complete the most steps”.

As the devices become evermore intelligent, so does monitoring. “Future devices will help companies to monitor stress through heart rate, respiration and sleep,” says Neil Shah, author of the 10 Step Stress Solution. “We know that stress and lack of sleep can affect productivity greatly.”

Mr Shah, whose organisation, Stress Management Society, has worked with companies such as British Airways and Shell, explains: “If we can go into a business and demonstrate stress is costing, say, £2.1 million per year through staff turnover, productivity loss, absenteeism and accidents, it’s a no-brainer. We can show that investing £50,000 on wellbeing can take out 30 or 40 per cent of that cost.” Companies often make the investment in green spaces, sit-stand desks or meditation rooms.

Micro wearables firm Humanyze, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology spinoff, is using its wearable monitoring to show interaction quality. Humanyze people analytics teams equip staff badges with sensors that track interactions, location and posture, and measure tone and speed of conversation.

Ben Waber, chief executive, explains that instead of using “error-prone” surveys and interviews, companies can now “understand how employees actually communicate, collaborate and work”. He adds that the data informs “everything from workplace design to team structure, to training programmes”. Companies ranging from oil field giants to Deloitte and Bank of America have used the technology.

Employee endorsement

It is hard to imagine a manager who would not consider such monitoring to improve productivity. But the implications for employees are concerning as many feel digital monitoring means a lack of humanity from management; programmes must be led by staff.

“The most important thing to consider is involving employees in any process of instituting cameras and sensors,” says Todd Thibodeaux, president and chief executive of US IT industry association CompTIA. “Before the devices can do any good, employees have to trust they are being used for the right reasons.”

Representative employee teams should be involved from the outset, says Mr Thibodeaux, and the benefits, such as a better workplace, must be demonstrable. “There is a ‘big brother’ aspect to all forms of sensors and monitoring, and if employees feel they have not only a say but a vested interest, programmes will be a lot more successful,” he says.

Trust has to be established from the top down. “It must be easy to see management being monitored themselves and for staff to choose participation,” adds Mr Shah.

Finally, laws must be written to protect staff. Dr Waber says monitoring privacy needs to be part of regulation, “namely that all behavioural data collection should be opt in, [and that] only non-individual and anonymous data should be provided to an employer, not recording communication content”.

There is enormous potential for monitoring to improve office design and the technology’s adoption is as good as inevitable. But trust, choice, safeguarding and team involvement are essential if any such programme is to be beneficial.

Positives