If you’re old enough to remember the fax machine, you may not have seen one for many years, unless you happen to work in the NHS. Last year, the Royal College of Surgeons revealed that more than 8,000 fax machines were owned by NHS trusts, and described it as “ludicrous” that so many trusts were still using the “archaic” machines for communications and transmitting patient data.

In the rest of our daily lives, we are used to digital technology, whether we’re checking our bank accounts from our smartphones or making bookings online. When it comes to NHS technology, Don Redding, director of policy for National Voices, a coalition of health and social care charities, says there’s a clear need for improvement.

It’s actually easier to secure electronic information than it is to secure papers lying on the table

“We believe frustration is growing that the NHS can’t do basic things that other technology-enabled industries can do, such as keeping you informed of the progress of a request or joining up your customer information all in one place. The consequences of these things are very real,” he says.

There is a commitment to improve NHS technology, which has the potential to transform patients’ lives by giving them more involvement in their own healthcare. It could allow clinicians instant access to information to help them look after their patients more effectively and improve diagnosis, as well as helping to plan services and evaluate policy decisions.

How digital technology can bring real healthcare benefits

There are wider benefits for health research where access to national patient data has the capacity to inform advances in understanding diseases, to help in the development of new treatments and prevention of illness.

When it comes to NHS technology, GPs have been ahead of the game on digital systems. A doctor from Devon was the first GP to use a computer in consultations in 1970 and by 1975 a nearby health centre became the world’s first paperless general practice. Today many of us book GP appointments or put in repeat prescription requests online or on our phones.

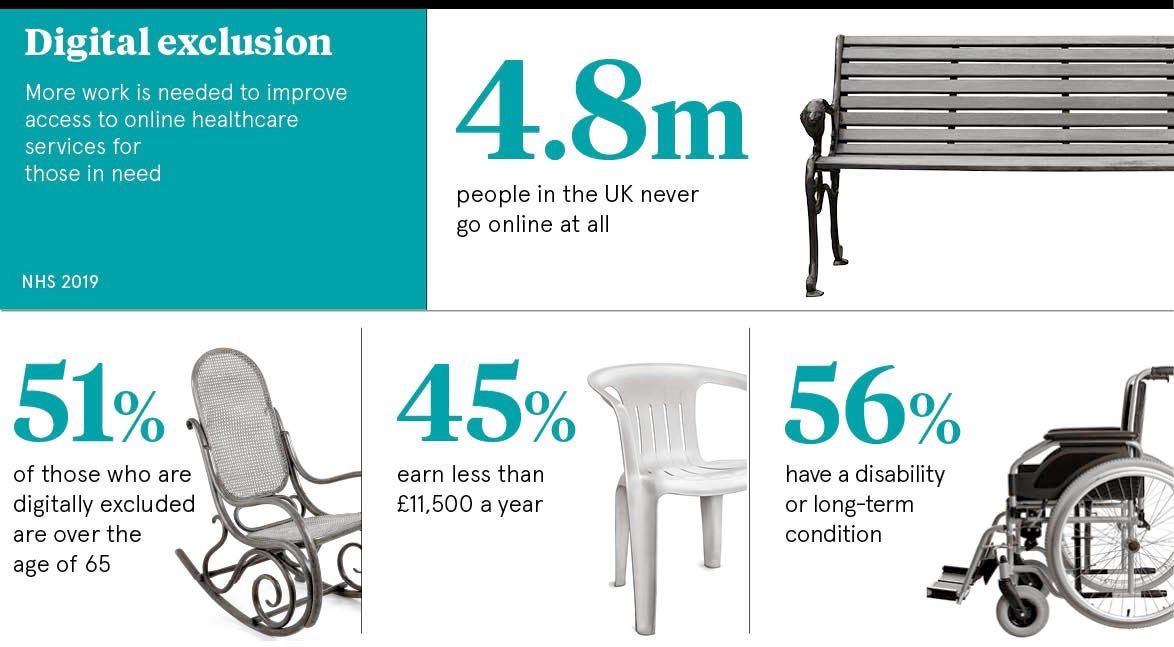

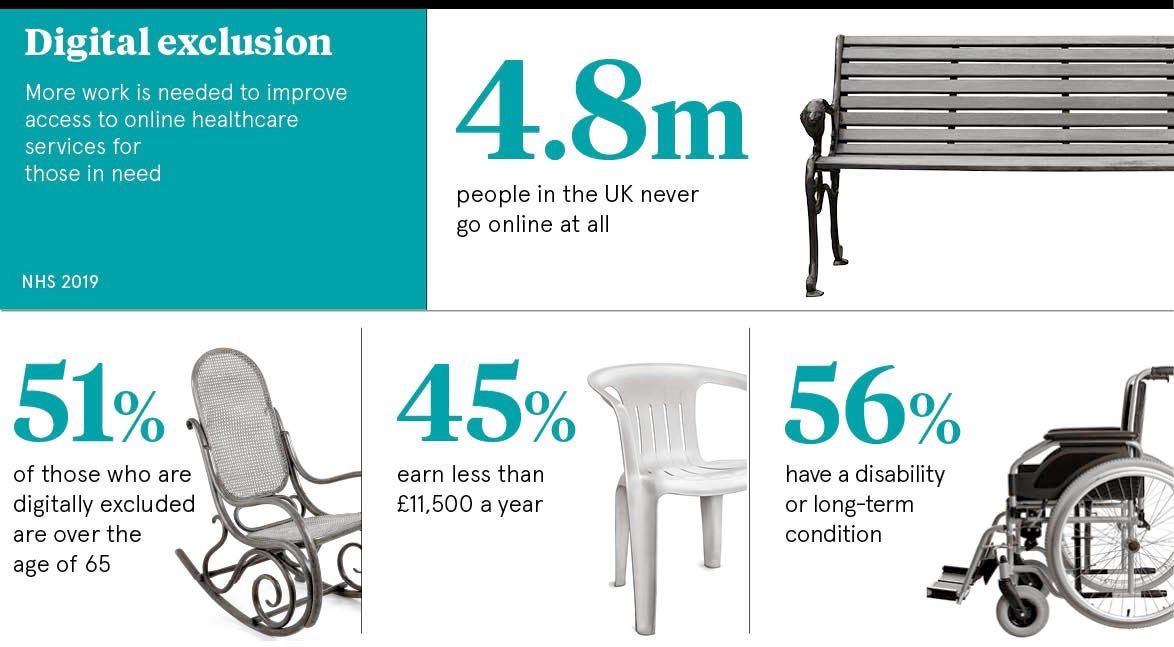

Some patient groups, for example the elderly or those on low incomes, may not be able to benefit from digitalisation if they do not have easy access to the internet or smartphones. Harry Evans, a researcher at the King’s Fund, believes that designing systems with these groups in mind could present an opportunity to offer better care. For example, there have been computerised pilot schemes reaching out to rough sleepers to engage them in digital healthcare using tablets and others teaching older people how to use technology.

As Mr Evans explains: “If you do things at a population level, you risk cutting out some groups. These risks can be mitigated though and there is a lot of evidence about how to design technology specifically to appeal to those people. If we believe technology is important, why don’t we use it to improve care for the groups we’ve struggled to reach?”

Will patient data be safe in a digital NHS?

It may sound positive, but there are concerns about how secure patient data might be in an entirely digital NHS. This is information about people’s most intimate and personal details, and keeping it safe is vital. Just two years ago, in May 2017, a global WannaCry malware attack affected nearly 600 GP practices and at least 80 NHS trusts, leading to thousands of cancelled appointments and operations. Many NHS staff were unable to access computers and equipment such as MRI scanners and devices for testing blood and tissue samples.

A Healthwatch poll last year found that more than half of those who were aware of the WannaCry attack said it had made them less confident in the ability of the NHS to protect their data. Despite this, a clear majority were happy for the NHS to use their information to help improve treatment for others and still had trust in NHS technology.

National Voices’ Mr Redding says it’s all about patients being kept in the picture and involved in decision-making. “What people don’t want is for our information to be shared without our knowledge and consent, and without an understanding of how it will be used,” he sys. “We need clear systems of consent and data protection. But actually, like most regulation, people just need to know that it is in place and that they can trust their NHS with their information.”

Going digital could actually lead to greater data security

Of course, patient data does not have to be online to be vulnerable. In 2017, it was revealed that more than 700,000 NHS paper documents had gone missing, including letters about tests, treatment plans and cancer diagnoses.

Mr Evans at the King’s Fund says the real risks for patients with digital technology may not be about the security of patient data. “It’s actually easier to secure electronic information than it is to secure papers lying on the table, but it’s not difficult to lock systems down in the way that we saw happening. That does have the potential to impact patient care in a way that previously didn’t happen. The NHS wasn’t ready for it and has to be prepared,” he says.

The future has to be about careful preparation and finding technology that can bring together the wide range of systems used in healthcare. But it is also crucial to work with patients and medical staff to find solutions clinicians can use easily and which bring clear benefits to those they care for.

How digital technology can bring real healthcare benefits