Out with the old, in with the new. The idiom may be trite, but it is the most apt of descriptions for the digital revolution that it is sweeping all before it. Innovation continues apace, transforming the media and entertainment landscape with a rapidity that surprises even those who like to cast themselves as digital revolutionaries.

Old media, or legacy media, are losing audiences by the day. As those terms suggest, there is little sympathy by new media enthusiasts for platforms they now regard as existing beyond their sell-by date.

Declining ad revenues

Newspapers, the ones printed on newsprint, are the most obvious victims. Overall sales of the national titles are falling at a rate of about 10 per cent a year while regional dailies are declining faster. Local papers, which initially bucked the downward trend, have also seen their sales tumble over the past decade.

Yet the digital audience for newspaper content has increased to levels that far exceed the numbers they enjoyed at newsprint’s circulation zenith in the 1960s.

Editors happily point to the millions of people who access their websites. By contrast, their owners and commercial managers sadly point to the financial reality: advertising revenue, the lifeblood of newspapers for more than 150 years, is taking flight.

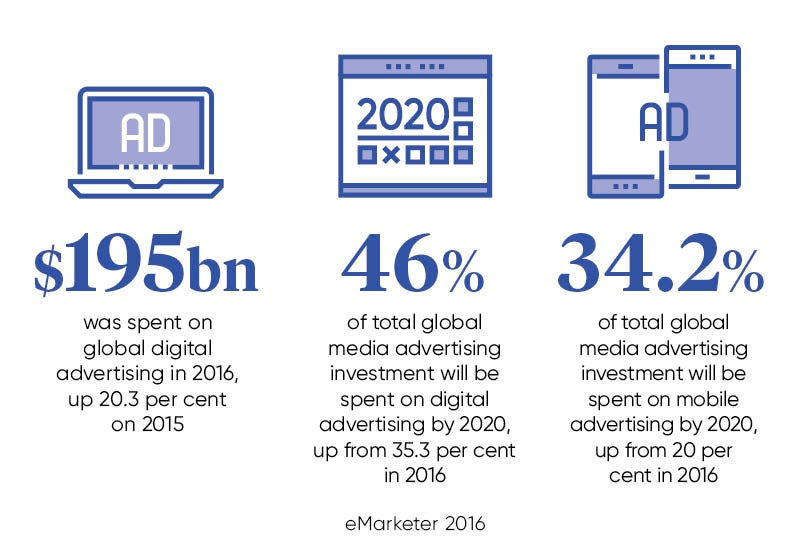

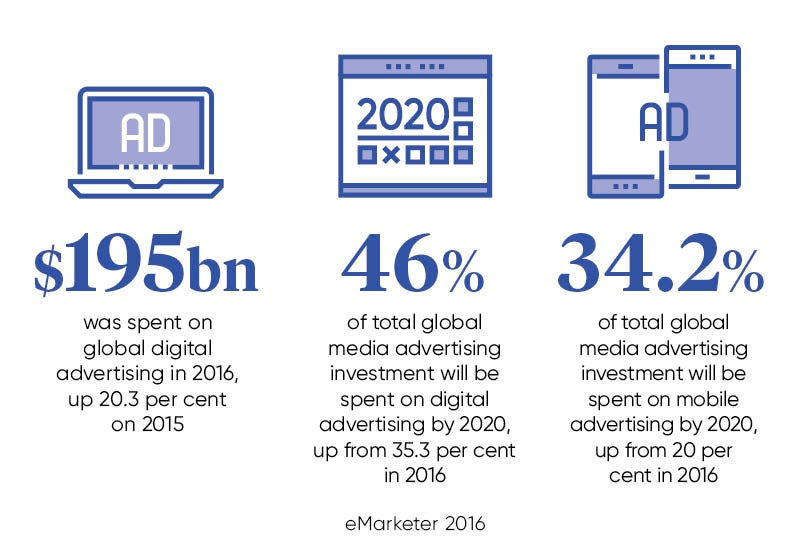

In the jargon of the newspaper trade, newsprint pounds have been replaced by digital pennies. Monetising content has proved more difficult than first appeared because advertisers and their media-buying agencies prefer to seek consumers through social media and, of course, the internet behemoth that is Google.

Their reasoning for the switch from traditional advertising outlets to online alternatives is understandable. In this increasingly connected world, it is easy to track and measure performance. The data is easily available and enables advertisers to target consumers more efficiently, and cheaply, than ever before. They can guarantee that their goods and services reach the right people.

This facility is one of the major reasons for the recent prediction by PwC that the UK media and entertainment sector will grow at a rate of 3 per cent a year, making it worth £68.2 billion by 2020.

Mobile-first publishing

The other key factor is all about the increasing use of a single platform: mobile. Hand-held digital devices are so user-friendly. People scan them throughout the day, for news, entertainment and information.

On train journeys, they watch films and TV series. At bus stops, they reel through their Facebook listings. In the office, they catch up on breaking news. Nor are they passive consumers because they take their own pictures and shoot their own videos, uploading them to a favoured site within seconds.

This is the dynamic environment of unmediated media. Call it the democratisation of publishing. Users take part in an unending series of conversations in which people pass each other links. Sharing is one of the clearest ways to discover what people like and want.

One significant set of user recommendations involves TV and movie content. It often results in instantaneous online viewing, a phenomenon that is gradually replacing TV-set viewing.

According to PwC, the enduring love for television and film output is likely to account for more than 35 per cent of consumer spending on media and entertainment in 2020. It believes TV will be the fastest growing digital sector, with advertising revenues growing at 19.6 per cent a year.

Although all is not lost for established companies, the direction of travel is clear

As with the clicks that betray people’s advertising choices, their habitual watching of TV programmes and movies reveal their desires and enable the entertainment industry to provide personalised experiences.

Schedules are no longer relevant because time-shifting is common. On-demand viewing is growing in popularity, especially with the increase in programme production by Netflix, Amazon Prime and Sky TV.

These new entrants have invested money in quality programming and, in so doing, have challenged the monopolies previously enjoyed by the former terrestrial TV companies. Other audience-building initiatives, such as the promotion of box sets of old series, have also been welcomed by viewers.

Consumers are driving this inexorable progress towards a digital-only world where there is no such thing as the status quo. Seemingly aware of living through a period of permanent change, they are adept at adopting new developments in mobile hardware.

Seeking what amounts to real-time instant gratification, they eagerly seize every tablet and smartphone innovation, thereby boosting mobile penetration towards an expected 90 per cent in three years’ time.

The future

In this new media landscape, with its persistent disruption of traditional providers of news and entertainment, there are, inevitably, winners and losers. Jonah Peretti, chief executive of BuzzFeed, would surely argue that he is among the former.

His company lays claim to an audience of more than half a billion people across a range of platforms and he says revenue, which totalled $167 million in 2015, grew by more than 65 per cent last year. And that followed six years of double-digit revenue growth.

As impressive as that sounds, it pales by comparison with Facebook’s 2016 revenue of $27.6 billion and Google’s $74.5 billion. These hugely profitable enterprises have been the major disrupters, wrecking the advertising-dependent business models of the media companies they have supplanted.

Although it does not mean that all is lost for established companies, the direction of travel is clear. No wonder so many chief executives across established media and entertainment are pessimistic about the prospects for their businesses.

They are caught in a bind. Although they know they must adapt or die, they are acutely aware of the financial problem it presents. Digital invention involves a level of investment, including the probable hiring of new staff, that threatens the bottom line for companies already finding it difficult to sustain profitability.

Nor, of course, is there any certainty that any such commitment will result in success. Better instead to manage decline and cede the ground to the digital disrupters?

Declining ad revenues