Elizabeth Warren is a US politician and the woman most likely to run against President Donald Trump in 2020. Earlier this month, she attempted to discredit Trump’s pick for attorney general by reading a letter from Martin Luther King’s widow. Barred from continuing to do so from the floor of the Senate, she took to Facebook Live instead. To date, the video has registered more than 12.5 million views.

Senator Warren’s actions are the new normal. New because live streaming via a mobile device is a relatively recent phenomenon. Normal because for two decades the internet has been democratising the tools of mass communication. Live video is just the latest way to reach large audiences unmediated.

The dominance of Facebook Live

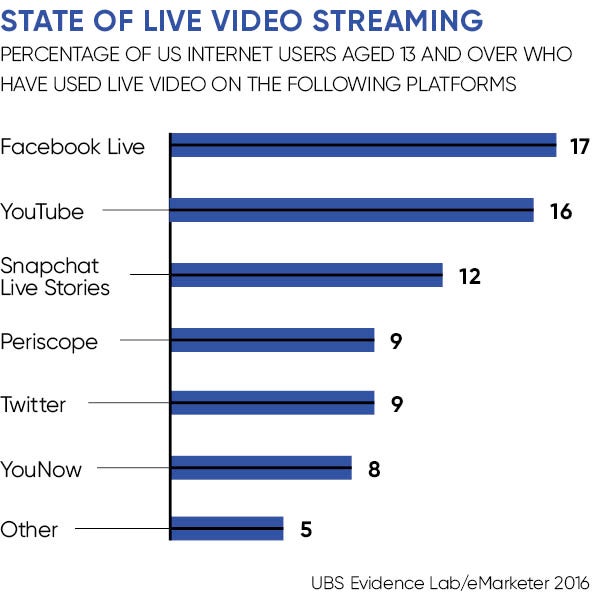

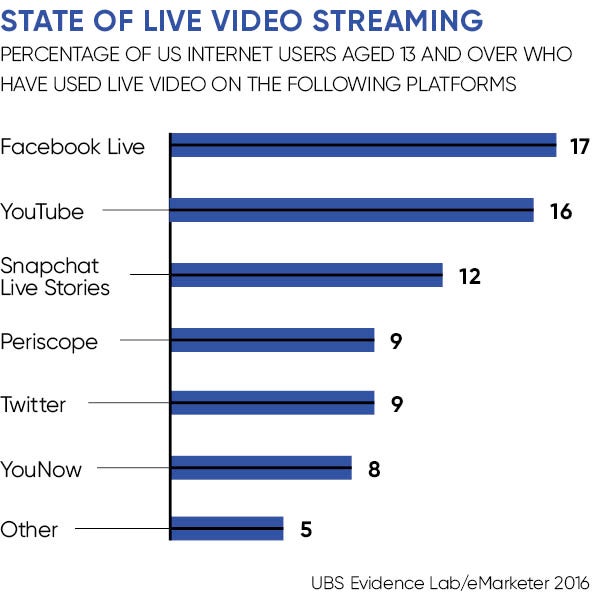

The Elizabeth Warren video tells us something else as well. Less than a year after its launch, Facebook Live has become synonymous with live streaming. Announcing the service last April, founder Mark Zuckerberg promised to put “a TV camera” in all our pockets. And yet we already had one or at least the opportunity to access mobile apps that did just that. Twitter’s Periscope and the social network-agnostic Meerkat launched in March 2015 while webcasting service YouNow had a four-year jump on both. Nevertheless, Facebook Live appears to dominate. So much for first-mover advantage.

“There’s a saying in Spain, ‘The second mouse gets the cheese’,” notes Drew Benvie, founder of social media agency Battenhall. “Facebook saw something that worked and, like so often, copied it and put it on a much bigger canvas.” It’s not just its scale that gives Facebook an advantage – 1.86 billion active users a month against Twitter’s 319 million – but its wider demographic reach – more celebrities, more brands and more countries. Two thirds of those most actively live streaming are doing so in languages other than English, according to analysis by Socialbakers.

Live video is the latest way to reach large audiences unmediated

At the BBC, Radio 1’s Newsbeat has largely swapped Periscope, used heavily during the 2015 UK general election, for Facebook Live. The news programme produces one live stream a week on average, typically on location. Reporting from the US-Mexican border during the recent presidential election, for example, viewers were granted a guided tour from a border patrol officer. “Young Newsbeat Brits were able to put their questions directly to someone they would never get to speak to otherwise,” says Newsbeat’s digital editor Anna Doble.

Ms Doble believes it’s this interaction that gives live the edge over recorded video. “It compels people to ask in-the-moment questions,” she says. And while a request on Twitter might generate six questions, Facebook Live generates 60 questions. She adds: “That’s a real appeal to news organisations.”

Newsbeat is learning what works and what doesn’t. Visually compelling content works. Regular updates work too because few viewers watch the entirety of a stream. “Treat it like a rolling news channel,” says Ms Doble. When they get it right, a Facebook Live stream on the main Newsbeat page can attract 100,000 viewers.

User-generated content

Individual success stories are one thing. Understanding in aggregate how many people are creating and viewing Facebook Live is quite another. Why? Because while Facebook is happy to share its headline user-base, it is reluctant to do the same for Facebook Live. It will say that the number of people broadcasting live at any given minute grew four-fold between May and October 2016. It is also understood that people watch live streams three times longer and comment ten times more often than with recorded video.

As for the most viewed Facebook Live, it’s an undeniably trivial but riotously joyous piece-to-camera featuring a 37-year-old woman showing off her newly-purchased Star Wars mask. Chewbacca Mom has clocked up 164 million views.

Still, a lack of absolute numbers and an initial decision to pay some media companies and celebrities to create content, plays to a narrative that take-up may not be as high as hoped. Elsewhere, there are reports that video engagement is lower than imagined. A report by analytics firm Parse.ly found that users spend more time engaged reading text posts than watching video. The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University found similarly.

Despite this, Battenhall’s Mr Benvie insists that live video, regardless of provider, is here to stay. Asked how he advises clients to use it, he says: “It’s not how but who. The best examples are from individuals or brands where live video is part of how they communicate.” The likes of Red Bull, General Motors and Land Rover – the latter live streaming test drives – have all experimented. By going live, these brands aim to do what Elizabeth Warren did – cut out the media middleman. Live video is now part of the content marketer’s toolbox.

So where next?

Will live video prove a gateway to other immersive storytelling techniques? Ms Doble at Newsbeat thinks so. She imagines, as an example, a large protest enhanced by augmented reality and 360-degree visuals to give the viewer, in person or watching remotely, an opportunity to interact with other protestors.

Mr Benvie believes the next stage to a more immersive live video experience will see it integrated with the “story” feed, a concept first popularised by Snapchat that allows users to chart the day’s events in a series of ephemeral multimedia posts. Borrowing from its parent company’s playbook, Facebook-owned Instagram replicated the idea and called it “Stories”. Last month it added live video. “Over the next year, we’ll see live video and Stories growing hand in hand,” predicts Mr Benvie.

The dominance of Facebook Live