The ticking of an antique clock in the oak-panelled boardroom may provide customers of traditional wealth management firms with the reassurance they need as they commit to buying emerging-market equities, Silicon Valley technology stocks, Venezuelan bonds or whatever else their pinstriped adviser is recommending that day.

However, for proponents of low-cost digital and automated investment adviser services, sometimes called robo-advisers, this is an outdated and expensive model that’s past its sell-by date.

A data-driven revolution is sweeping through the investment industry and firms that fail to recognise it risk losing business to more fleet-footed digital rivals as their wealthy clientele grow increasingly comfortable with the use of new technologies when making their investments.

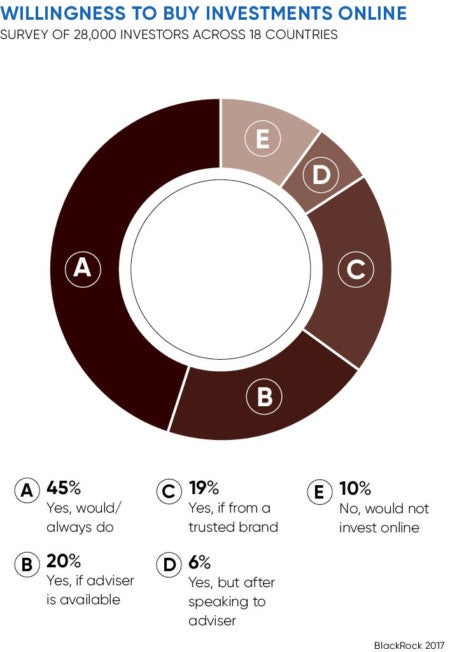

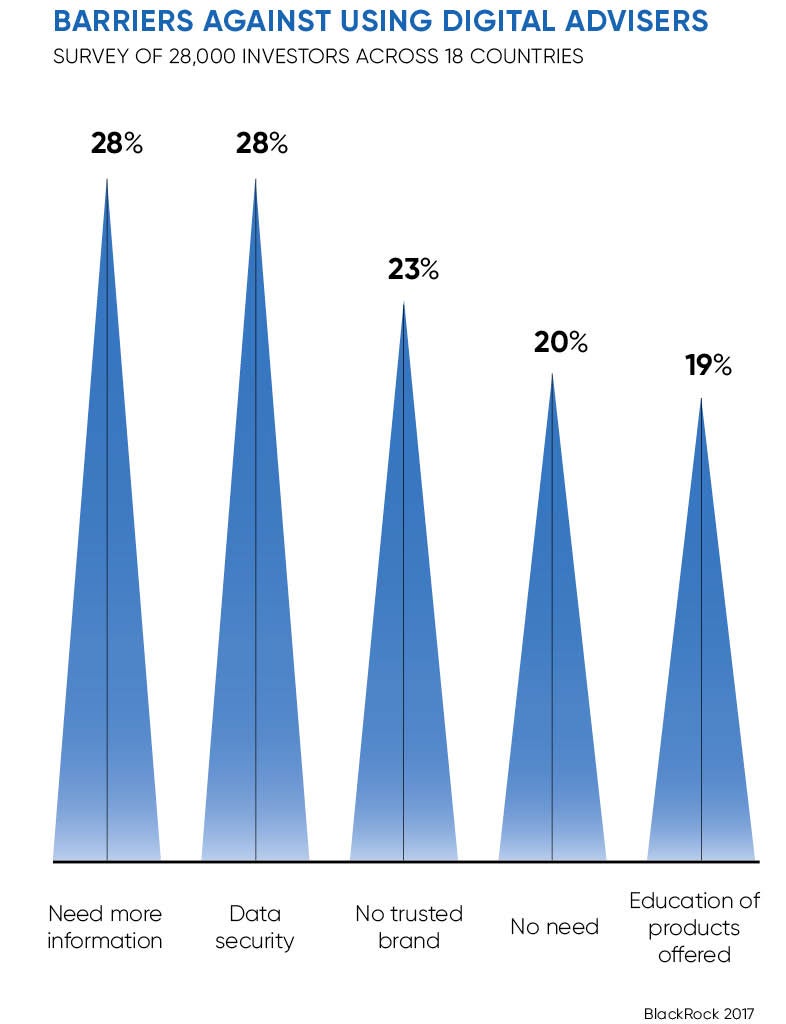

Survey after survey shows that millennials, and indeed most potential investors aged under the age of 60, are happy to entrust their savings to a digital platform or mobile app, so long as it’s credible, secure, trustworthy, capable of offering them a range of low-cost funds and some personal investment advice.

The robo-advisers are predominantly targeting ‘Henrys’ or ‘high earners (who are) not rich yet’

“The idea that you have got to become best friends with a man with cufflinks and an expensive watch to get financial advice is becoming harder and harder for people to swallow,” says Mark Polson, founder and principal of specialist consultancy The Lang Cat.

The robo-advisers – essentially websites that rely on online questionnaires, artificial intelligence and algorithms to steer clients into appropriate, low-cost investment portfolios – are, at the moment, predominantly targeting what the Financial Times calls “Henrys” or “high earners (who are) not rich yet”.

They’re doing this by undercutting traditional wealth managers on cost, ease of use and minimum sums invested. Adopting mantras like “We’re democratising wealth management”, such players generally steer their clients into low-cost exchange-traded funds, which are able to mirror the movements of stock market indices at a fraction of the cost of active funds.

Some believe that these robots are going to be able to storm the citadels of wealth management simply because they are more honest and reliable than fallible human beings.

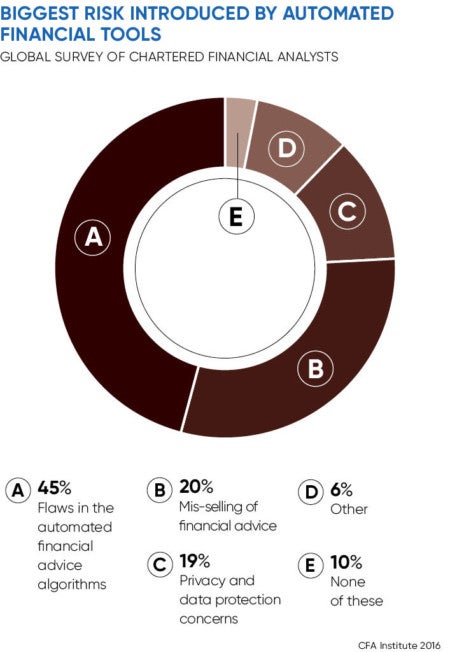

Kunal Bajaj, founder and chief executive of Mumbai-based Clearfunds, says using technology to crunch financial data, automate processes and eliminate excesses – “the fancy lunches, the plush offices and the overpaid staff” – reduces the risk that investors will be “cheated into products that are too expensive or not right for them”. In a recent blog post on his firm’s website, Mr Bajaj says “a good robo-adviser is transparent, unconflicted and unimpeded by human biases and prejudices”.

Robo-advisers are also being given a leg-up by the authorities. Both the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and Treasury see them as a means of plugging the advice gap that is currently bedevilling the UK investment market, and which has widened since the banning of commissioned-based selling in 2012.

Under new chief executive Andrew Bailey, the FCA appears to have traditional wealth managers and asset managers in its sights. In a barnstorming Asset Management Market Study Interim Report, published last November, the regulator as good as accused traditional players of colluding to rip off their customers. The FCA set out a package of proposed reforms including a strengthened duty on asset managers to act in investors’ best interests, the introduction of an all-in fee and measures to boost transparency.

However, there is scepticism in some quarters about the scope for robo-advisers to disrupt the wealth management sector. The problem facing the robos isn’t technology, building cool stuff, having good ideas or even managing money, it’s finding customers. And the cost of acquisition per client in that sector is way too high. It’s up to hundreds of pounds per client. Many of these firms will be lucky to make their money back, ever.

There are also worries of how they will cope in a bear market, when investors are seen as needing more hand holding, as well as their inability to take tax planning and succession planning into account.

The rise of robo-advisers

The robo-advisers, which only really came into being after the financial crisis of 2007-9, are still quite small beer in the ocean of money. Mr Polson says that in the UK they have, at most, a combined £1 billion in assets under management. That compares with a wealth management sector that has more than £550 billion of assets. “The disruptors are doing some really interesting and exciting things but, outside the commentariat, they have yet to make a serious dent in the market,” he says.

Of the robo-advisers in the UK, the largest is Nutmeg. Launched in 2012, it has so far raised £71 million in five funding rounds from venture capitalists and others. Nutmeg has more than £600 million under management, though it remains loss making, and escalating marketing and advertising costs meant that in 2015 its losses widened from 2014. It also last year lost its founder and chief executive Nick Hungerford, though he remains as a non-executive director. Earlier this year Nutmeg trimmed fees. These now stand at 0.75 per cent on the first £25,000 invested and 0.5 per cent on portfolios worth more than £100,000.

Other UK players include Wealthify, launched in 2015; MoneyFarm, launched in Italy in 2012, and in the UK in 2016; and Scalable Capital, launched in 2016.

These players are following in the footsteps of more established firms in the United States, including Betterment, which was launched in 2010, and Wealthfront, launched in 2013. They already have, respectively, $8.9 billion and $5 billion in assets under management. Analysts at Citigroup predict globally robo-advisers will be managing $5 trillion over the next decade.

Schroders, with £375 billion in assets under management, seems to be more alert to the risks posed by the rise of the robos than some of its peers. Among the strategic risks it lists in its 2016 annual report is “increased investment and asset allocation through robo-advice services, displacing active management”. Schroders says it has sought to mitigate this by embarking on a number of “digital initiatives… to improve client experience, engagement and servicing through our web and mobile platforms”. These have included paying a reported £12 million for a minority stake in Nutmeg.

Other finance players are also acquiring robo-adviser or hybrid firms, or developing their own. So, in the summer of 2015, asset management giant BlackRock acquired San Francisco-based FutureAdvisor, while Invesco acquired California-based Jemstep and Santander took a stake in SigFig. Fidelity has developed FidelityGo, while Charles Schwab launched Schwab Intelligent Advisory and UBS developed SmartWealth, which is designed to appeal to younger investors.

Brewin Dolphin has launched a robo-adviser that allows customers with between £10,000 and £200,000 to invest in one of six model portfolios at a cost of 0.7 per cent of invested assets, plus underlying charges of between 0.11 per cent and 0.16 per cent.

Harry Morgan, key client director at wealth manager Tilney, which has £22 billion under management, says: “We see this as a really exciting area, which will enable us to make our products and services accessible to people with smaller pots of capital and to expand the market at the same time. People tend to see all disruption as an attack. Actually, disruption can expand the overall market.”

Anybody who doesn’t have some degree of automation and a decent online user experience will find themselves marginalised

Vanguard, which introduced a hybrid robo offering called Personal Advisor Services to the US market in May 2015, is launching something similar in the UK, though this will not technically be a robo-adviser as it will only sell Vanguard’s own bunch of tracker funds. Mr Polson predicts that because of low annual management charges of just 0.15 per cent, Vanguard’s UK product will be “as disruptive as all the robos put together”.

So what should traditional wealth managers be doing to see off the threat? Mr Polson says there are three main things. “If they’re serious about fending off these upstarts, they’re going to have to improve their transparency. They suck at transparency,” he says. “Secondly, they’re going to have to improve their customer experience; wood-panelled rooms, expensive wristwatches and chocolate biscuits are one thing, but I can get on to Scalable Capital’s website on my iPad and have an experience that looks like it’s from 2017 as opposed to 1926. Thirdly, they’re going to have to react to fee pressure and the only way to do that is to demonstrate value.”

He predicts that in future the robo sector will no longer be regarded as a discrete area of the investment market “If we look forward five years, what we understand as robo will just become part of what people do, and you’ll be able to mix online and offline and transact in a way that suits you best,” Mr Polson concludes. “Anybody who doesn’t have some degree of automation and a decent online user experience will find themselves marginalised into a shrinking, very traditional space.”

The rise of robo-advisers