Proactive spending on predictive maintenance techniques helps determine the condition of equipment so rail network operators can plan the best time to carry out maintenance work.

Nick Hughes, director of Hitachi Rail UK, explains: “Our digital systems use over 40,000 sensors on the trains to deliver real-time updates to the depot, so gone are the days where a train fault could only be investigated at the end of the day. Once a sensor picks up an issue, it is immediately relayed to the depot so they can prepare work.”

Only replacing parts as needed can save up to 15 per cent on the cost of materials, while the time taken and wastage is cut because maintenance teams know exactly which parts they need to service and when. Train operators can provide more capacity using fewer trains because rolling stock is available for longer as it is spending less time in the depot.

Such an approach seems obviously more efficient, so why isn’t it used across the UK rail network?

Investment supporting rail modernisation

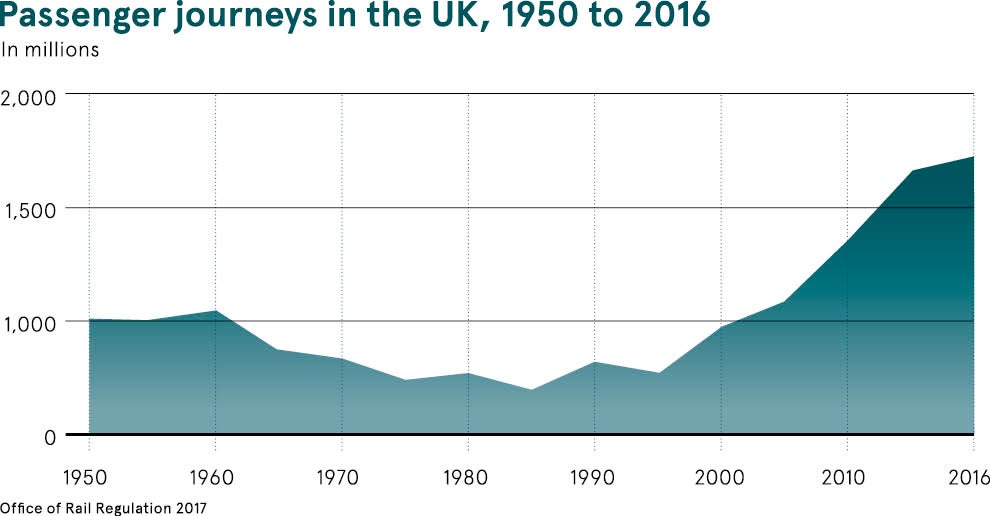

The biggest challenge for UK railways is keeping up with demand. Since privatisation in the 1990s, rail use has doubled and it’s expected to do so again in the next ten years. There are currently more than 1.7 billion rail journeys every year in the UK.

Euan McLeod, head of infrastructure for HSBC UK Commercial Banking, says: “Rail operators and rolling stock financing vehicles are successfully supporting the modernisation of the system, including investment in stations, trains and better services. More of this should be encouraged, and even extended into tracks and signalling where investment is needed. There is real appetite from private finance to support rail investment in the UK and at record low interest rates too.” The question is whether resources are being deployed in the most effective way.

One area where the UK seems to be staying ahead of the curve is with rolling stock. Companies such as Eversholt are backed by banks and own much of the rolling stock leased by operators. With more than 6,500 carriages estimated to be coming on to the market in the next decade, it seems likely that peak demand can be met.

Rail infrastructure costs outweighed by long-term benefits

The infrastructure surrounding rail has also received a boost through projects such as Thameslink and High Speed 2. As Mr McLeod points out: “Rail investment is often characterised as a raw cost when in fact this is outweighed by the long-term economic benefits to users and wider society in terms of improved connectivity, mobility, journey times and congestion.”

From King’s Cross in London to the remodelling of Leeds Station, gateway hubs developed around rail networks can boost regional connectivity and provide an economic boon for the region.

Paul Hirst, head of transport at Addleshaw Goddard, says: “Transport improvements can transform the cultural and socio-economic status of the urban environments they inhabit, not least through job creation. It is the combination of wider economic and social benefits that makes such a compelling case for investment in transport hubs.”

In Europe, high-speed rail has penetrated rapidly, connecting regions and boosting the popularity and performance of the rail sector, unlike in the UK where high-speed network developments seem frequently delayed or cut despite potential benefits. In May, rail think tank Greengauge 21 proposed a UK network of high-speed rail by 2050 to boost productivity compared with France, Germany and Spain.

UK falling behind in rail network digitisation

At the same time, the UK has been falling behind in the digitalisation and management of its rail network. Predictive maintenance may be gaining traction, but the UK still lacks significant investment in other digital technologies.

In Japan, for example, traffic management systems were deployed in the 1960s to help facilitate the bullet train. This has a direct impact on user experience. As traveller numbers rise, there is a growing need for more lines and better rail traffic management.

In the new Thameslink project, intended to improve passenger flow in and out of central London, Hitachi Rail’s traffic management system will enable the network to run 24 trains an hour, nearly as many as the London Underground. It will do this through providing cab signalling and computerised train control on part of the main line network.

Lack of digital in-cab signalling also slows the network and impacts user experience. Across Europe rail traffic is managed by such a system, known as the European Train Controls System. This enables trains to run closer together because it continually calculates the safe maximum speed for trains and can take control depending on whether permissible speeds are exceeded.

You only have to look at the rail experience delivered in countries such as Spain and China, which have proactively invested in high-speed rail and digitisation, to see the benefits of this approach versus maintain and fix

New technologies could mean new lease of life for UK rail networks

Systems which can track wind speed, fallen obstacles and other elements on the network only improve network management.

Mike Hughes, UK and Ireland zone president at Schneider Electric, points out: “You only have to look at the rail experience delivered in countries such as Spain and China, which have proactively invested in high-speed rail and digitisation, to see the benefits of this approach versus maintain and fix.

“New technologies have delivered a level of reliability we can only dream of in the UK. The Spanish high-speed network achieves 98.5 per cent punctuality and a five-minute delay is considered significant.”

Rail continues to grow in importance as a key part of a sustainable transport network and a lever for regeneration. To manage the scale of technology innovation and improvement, isn’t it time policymakers rethink their current approach to infrastructure spending in the UK?