Apathy, fear and dislike of hype have all played a part in ensuring the UK ranks just 11th in the world in terms of its digital readiness, according to the latest government figures. Yet for a growing number of businesses, it’s lack of access to relevant skills and education which is causing consternation.

Around one million workers will need to be reskilled or upskilled within the next five years to keep up with next-generation 3D printing, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, augmented reality and the internet of things, among many other innovations.

But while beefing up engineering talent on the shop floor is vital, skills gaps further up the food chain are also hitting home.

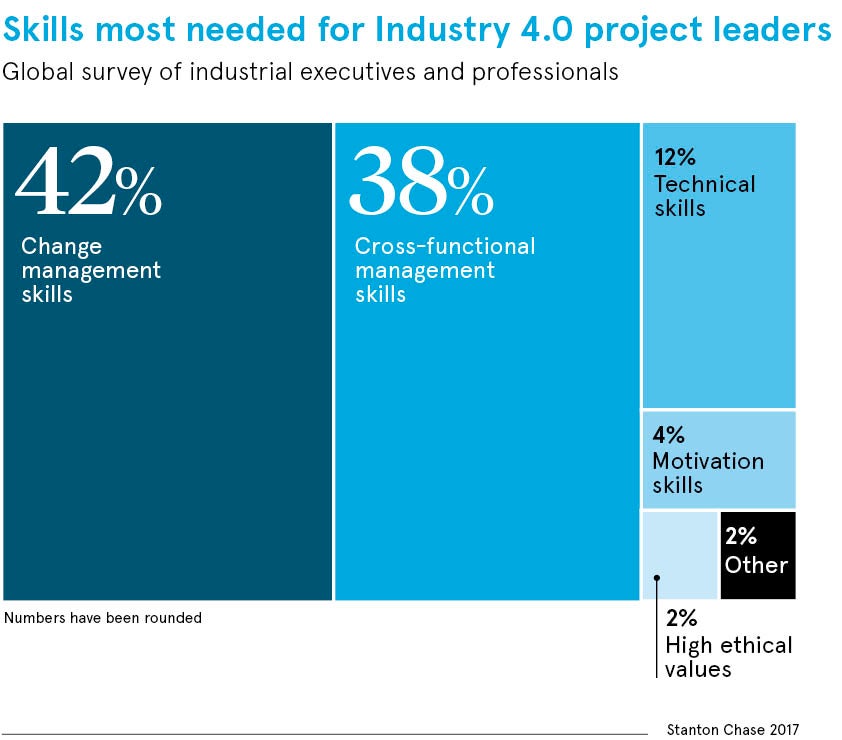

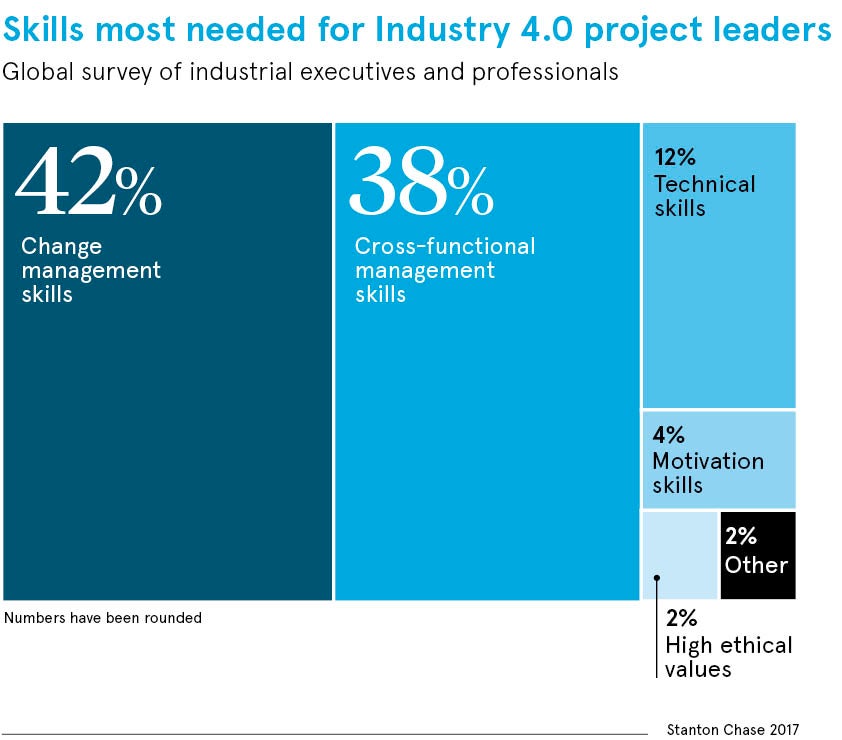

Overall, 30 per cent of respondents to the latest Stanton Chase Global Industrial Executive Survey say their biggest challenge in implementing industrial innovation is lack of technical skills, while 20 per cent say the same of leadership skills such as change management.

“It seems that there are frequent bottlenecks due to a lack of common understanding and, in some companies, the speed of execution is hampered further by layers of hierarchy,” according to Gert Herold, the executive search firm’s managing partner and vice president for Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

“It is a great challenge for the C-suite and talent management to prepare an entire organisation for workplace 4.0, to keep all seniority levels and age groups involved and motivated, and to safeguard permanent learning.”

For business leaders without a technical background, the problem is compounded, says the British Automation and Robot Association, whose president Mike Wilson notes that while there are already 170 robots per 10,000 employees in Germany, the UK figure is just 33.

“It’s worth remembering that leadership skills will become more important than technical ones and once we start to demystify the Industry 4.0 jargon, this will become clearer,” he says.

“In the meantime, if you’re a chief executive without a clear grasp of the various bits of kit people are talking about, make sure you talk to your own engineers before you fork out money just to make yourself and your company look good.”

So if the UK is in danger of being stuck at the back of the class when it comes to technological education, despite the trumpeting of new T-level technical qualifications, which of our direct competitors are grabbing all the A stars?

“Germany inevitably stands out in terms of its world-class apprenticeship system and I would argue that Italy is leading the way in terms of how its government encourages manufacturers to take the plunge via financial incentives,” says Laura Pickering, education development manager at the Manufacturing Technologies Association.

“But I’m particularly impressed by Spain, whose national strategy for industrial digitalisation – Industria Conectada 4.0 – has put lifelong learning and training at the centre of its digital skills strategy, while also addressing the issue of youth unemployment.”

She notes that while the rapid pace of change means that many of today’s engineering undergraduates will be out of step by the time they graduate, apprenticeships are less vulnerable.

Ben Rowland, co-founder of Arch Apprentices, concurs. “Germany is leading the way in technical education, but it’s not an easy model to follow,” he says. “While the work-study approach is deeply entrenched in the German culture, in the UK we’re still battling to get schools, employers and young people to see apprenticeships as a viable alternative to university.”

Ms Pickering stresses that while there is already an acute skills shortage in UK science, technology, engineering and maths, or STEM, we’re still missing a trick when it comes to gender balance.

“France, Germany and Spain have worked hard to attract more women to engineering, while we still have the lowest proportion of female engineers in Europe at just 9 per cent. This needs to change,” she says.

In the view of everywoman co-founder Karen Gill, Industry 4.0 could actually mark a turning point.

“Although men have largely dominated the discussion on Industry 4.0, it is a great opportunity for women too,” she says. “At a time when raw technical skills will need to be overlaid with emotional intelligence, better communication and more collaboration, women will come to the fore.”

Although business, science and academia are already working closely together via innovations such as Catapult centres, which echo the long-established Fraunhofer network in Germany, Mr Wilson fears an overload of blue-sky thinking.

“Having spoken to many small and medium-sized enterprises, I am convinced that what we need now is the sort of down-to-earth, practical training which will allow existing engineers to, say, put robots on packing lines via adaptations to a firm’s current technology, rather than buying in new,” he says.

What firms require is a clear automation strategy looking no further than five or ten years ahead

“What firms require is a clear automation strategy looking no further than five or ten years ahead, rather than thousands of MBA theses on what artificial intelligence will look like 20 or so years from now.”

Neil Lewin is learning and development consultant at Festo, which uniquely for the UK combines electrical automation manufacturing with industrial training. Its educational offer includes both introductory workshops on Industry 4.0 as well as site visits to a fully automated factory in Scharnhausen, Germany.

“Britain is at the starting point of its Industry 4.0 skills journey and, in many ways, so too is the rest of the world,” he says.

“My advice is to break down your educational needs into small chunks, and then mix and match the various training opportunities out there, be they executive coaching, factory floor training, whole-company workshops or indeed lifelong learning strategies.”