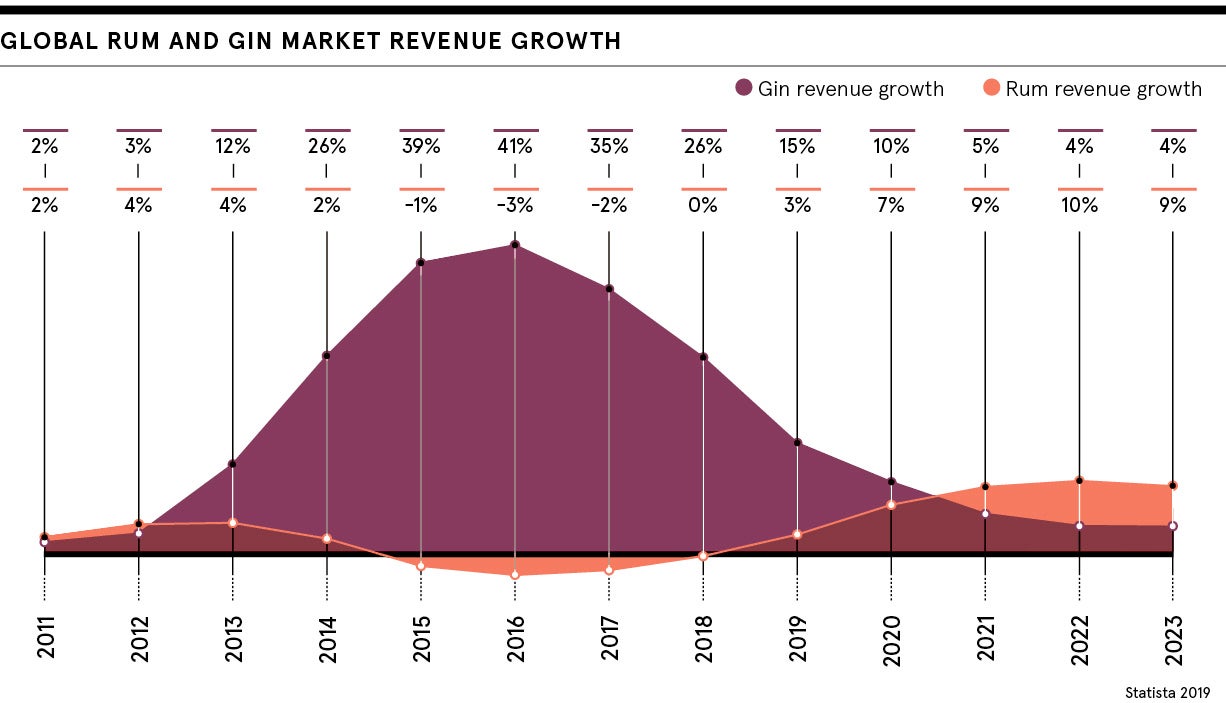

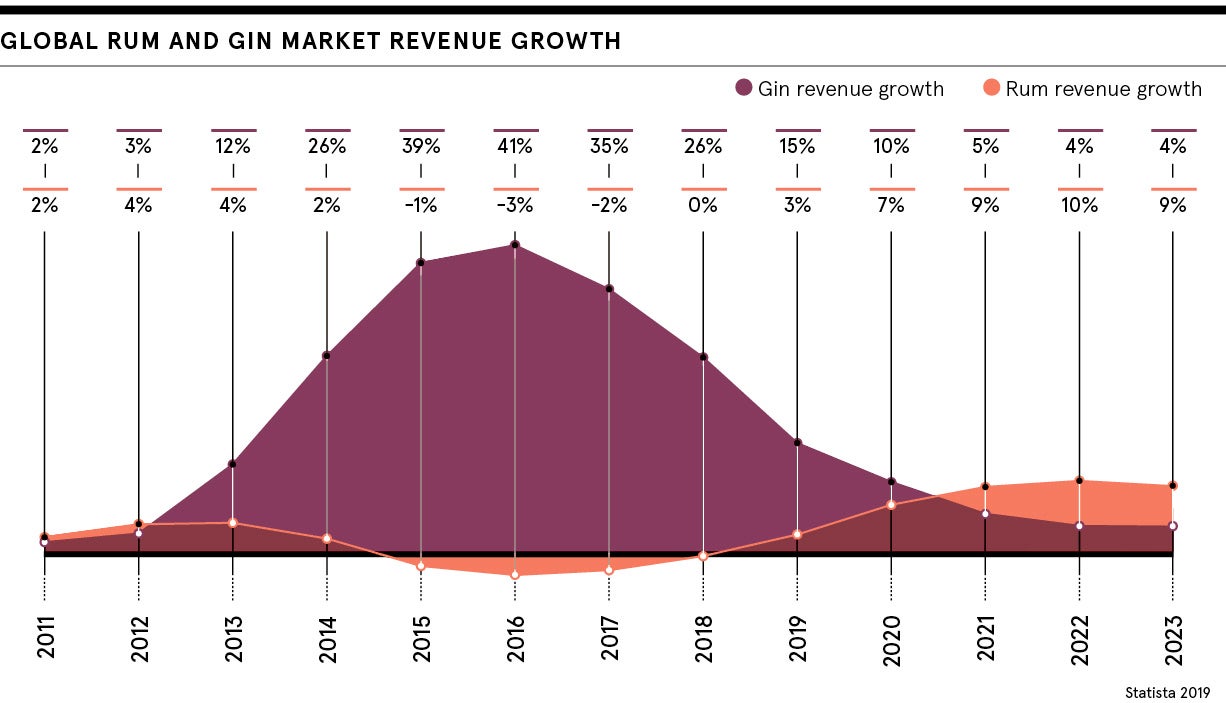

According to the Wine and Spirit Trade Association, annual UK gin sales are now worth £3 billion, with 76 million bottles sold a year. Rum, the rumoured next big thing, in contrast sold 35 million bottles. But research firm GlobalData says rum sales are currently growing at twice the rate of gin.

To assess whether a spirit like rum could dominate the UK spirits industry, we need to pay attention to the factors that made gin’s success so particular.

Firstly, its history ties it to the UK in a unique and deep-seated way. Cheap to distil and ruthlessly effective at numbing the pain of early modern urban existence, the botanical-infused elixir of “Dutch courage” transformed 18th-century London, provoking both regulation and riots, and was immortalised by Hogarthian caricatures.

Gin industry reclaiming its throne?

Today, however, it is savoured as something floral and cosmopolitan, crystalline and perfume-like. Its history and regal past allows it to hark back to a de-politicised aura of British-yesterday. The gin industry also benefits from the post-millennium rise of UK cuisine, with progressive consumers eager to try local and original produce.

Rum, on the other hand, is limited by its piratical and exotic mythology. In an era when local is fashionable, gin unsurprisingly has the edge.

To many working in the category, its success feels right. As the founder of Portobello Road Gin, Jake Burger, puts it: “Gin has justly reclaimed its place on the throne.”

With co-founder Ged Feltham, Mr Burger found himself at the forefront of the so-called “ginaissance”, and was excited to bring the history of alcohol to consumers and “in London, gin was the only story to tell”.

Rum being the next big thing has been something repeated by the trade press for years now. Rum is already a big thing

At his museum-cum-distillery The Ginstitute, visitors can learn about the spirit before bottling their own unique recipe. This focus on immersion reflects another trend in the wider world of alcoholic beverages. “The old model for the pub was and is failing,” says Mr Burger. “Fun, consumer-driven, educational experiences are a great way of driving footfall.”

Combining small-batch production with a historical back-story is common to many craft drinks companies and allows emerging brands to rival incumbents. But when everything scrambles to look authentic, the gap between the different products marketed begins to thin. Even the founder of Portobello Road Gin concedes: “I would be less inclined to launch a new gin now; the category is a little saturated.”

Accessibility and availability

The gin industry owes much success to its sparkling partner. Fever Tree made the point explicit: “If three quarters of your G&T is the tonic, wouldn’t you want it to be the best?” With the rise of bottled tonics, the category has seen a market-enhancing arms race from both sides of the G&T.

Rory O’Sullivan, a former gin ambassador, who manages bar accounts on behalf of Victorian tonic producer Franklin & Sons, explains the mutual dependency involved. “A good tonic brings out the flavour of a gin while at once making it both accessible and more grown up; it’s a spirit enhancer,” he says. By softening the alcohol burn, a tonic helps to bring gin to a broader demographic.

The wide consumer reach is also aided by the fact that distilleries can produce the spirit quickly. Due to space limitations, the base alcohol often has to be purchased elsewhere and flavours can then be added overnight. While the speedy production process might alienate some consumers, who assume a lengthy and effort-laden artisanal approach, it enables fast iterations and experimentations with flavours. This means it is relatively easy to make and produce new gins.

On the other hand, rum and especially dark rum takes a lot more time to age. Base ingredients of sugar cane and molasses are not easy to designate as British and their mixers less open to disruption.

Trademarking innovation

Led by the gin industry, the world of craft spirits is experiencing an intellectual property boom. In 2013, there were 1,199 registered spirits trademarks, while in 2018 there were 2,482. In its announcement detailing the increased number of trademarks across craft spirits, City of London-headquartered law firm RPC notes the especially strong performance of flavoured gins. In that specific category in 2018, sales had increased an astonishing 751 per cent compared with the previous year.

Alex Wolpert founded the East London Liquor Company in 2014 to “champion great booze at an affordable price point”. When reflecting on the increased number of trademarks across the category, he is sceptical about innovation across the industry. “We’re not reinventing the wheel; we are distilling spirits which has been done for a very long time,” he says.

In his view, trademarks are more important in allowing business owners “to sleep well at night” than impacting real day-to-day operations. When trying to discern how well a spirit is doing, Mr Wolpert says there is only one way: “Taste. Put it in a glass. Drink it. Assess it that way.”

Industry trends taking a darker turn?

The East London Liquor Company distils its own gin, but sells imported rum. Its founder doubts there will be a seismic shift in the industry. He says: “Rum being the next big thing has been something repeated by the trade press for years now. Rum is already a big thing.”

While it is in any industry’s interest for the market to appear in flux and for new stars to be emerging, the slowing of gin sales does not necessarily imply another spirit can or will take over as the country’s new favourite spirit.

Richard Harding, chairman of the Cornish Distilling Co, which makes its own UK-fermented, distilled and bottled rum, agrees there is no zero-sum game at play when asked whether rum could emulate the gin industry’s success. “We don’t think it is a question of either or,” he says. “Consumers of rum are not necessarily the same as consumers of gin.”

Similarly, Amy Mooney, head of Captain Morgan marketing, Diageo Europe, underlines the strength of rum without being drawn into the gin versus rum debate. “One in three cocktails served in bars, pubs and restaurants contains rum predominantly led by the mojito,” she says. “And we’re increasingly seeing spiced rum being used in new and interesting ways in the UK’s vibrant cocktail culture.”

Gin and rum can clearly co-exist, and while the 21st-century gin craze may be reaching its peak, there is no single group of trendsetters who are suddenly going to grow tired of craft gin when it loses its hipness, thereby sending the entire industry into disarray.

As Mr Wolpert concludes: “The trendy drinkers are probably quite a small percentage of the number of mouths in the UK that intake booze.”

Gin industry reclaiming its throne?

Accessibility and availability