It’s not just that employees can see companies now offer less job security and may have cut other benefits from traineeships to pensions. Workers, particularly millennials – those born between the early-1980s and early-2000s – expect a more flexible workplace to suit today’s fast-changing, connected world.

What’s more, the rise of social media and the mobile internet means employees are calling the shots. They are better informed and more likely to trust their peer group rather than corporations, at a time when the reputation of business has suffered in the wake of the global financial crisis.

According to the Deloitte Millennial Survey, carried out in 29 countries, 70 per cent of tomorrow’s leaders might reject what traditionally organised businesses have to offer, preferring to work independently by digital means in the long term. Welcome to the age of the demanding employee.

Technology has been the biggest driver of change. Younger workers want a more open, collaborative and flexible workplace, where staff can choose to work remotely and ideas are more likely to be shared on public social media platforms than on the company intranet.

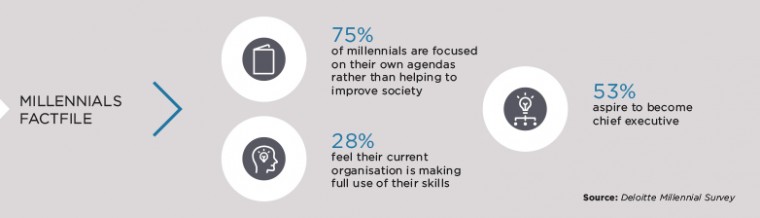

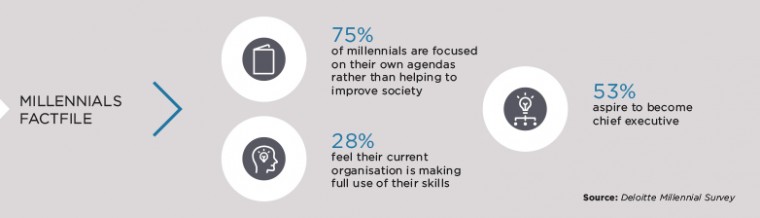

These millennials are also more tech-savvy than their managers and older employees. They are early adopters who expect to use the latest devices and apps they already use outside the office, regardless of whether an employer’s own IT department is using this technology. Only 28 per cent of millennials feel that their current organisation is making full use of their skills, according to the Deloitte survey.

The technology revolution has wider implications because the smartphone generation can see how fast the world is changing as new, agile, entrepreneurial companies from Google and Facebook to BuzzFeed and Uber disrupt the business landscape.

“The brilliance of the millennial generation is that they are imaginative, think laterally and believe they can do anything in the world,” says Amelia Torode, chief strategy officer at the UK arm of TBWA, the advertising agency which has Apple and Airbnb among its clients. “The down-side of millennials is their magpie nature. They are always keeping an eye out for the next shiny thing and – dare I say this? – they get bored when it comes to the details. ”

Employees’ expectations are different from the baby-boomer generation because the goals and aspirations of those entering the workplace are much further away and less attainable, according to Meriel Schindler, head of employment in London for the law firm Withers.

A generation ago, a young lawyer or accountant, for example, could expect to become a partner within five or six years. Now it is more likely to take a decade or more. Similarly, buying a home is less affordable for a debt-laden graduate. “Some of those goals have slipped beyond this generation’s immediate grasp,” says Ms Schindler.

Millennials also have less loyalty because they see how employers have cut permanent jobs in favour of short-term and contract roles.

Workers’ trust in business may have been further eroded by the behaviour of big corporations, which have been seen to act unethically

Andrew Linger, director of executive search at the recruitment firm Robert Walters, says: “Even before the 2008 financial crisis, the average length of service for a permanent employee had been falling, with some evidence suggesting it had dropped to under two years. That has almost certainly reduced further if you take into account the large-scale redundancies brought about by the recession. Loyalty has certainly been affected.”

Workers’ trust in business may have been further eroded by the behaviour of big corporations, ranging from banks to energy companies, which have been seen to act unethically. This has coincided with an explosion of social media and shared platforms, from Twitter and LinkedIn to Wikipedia and Glassdoor, which allow staff and customers to discover and share information easily. The Deloitte survey shows 75 per cent of millennials believe businesses are focused on their own agendas rather than helping to improve society.

While many workers may have had to endure a fall in real-term wages since 2008, they have gained other rights, particularly around flexible working, maternity and paternity leave, and diversity, and are willing to make demands on their employers.

Ms Schindler says allowing staff such as young mothers to work part-time or remotely has challenges. “It requires a higher degree of mental agility, remembering which people are available on which day. That’s the trickiness of it, smoothing the way with clients,” she says. “As a manager, if someone works flexibly, it’s a two-way street. I expect them to be available and to pick up e-mail.”

However, she adds there are “enormous benefits for everyone to flexible working”, citing the example of some Withers’ staff who have left London and moved to regional offices, where they are now able to work for clients at a cheaper hourly rate because they have lower overheads.

Ultimately, employees are more demanding because they are more aware of the work-life balance in an always-on era when it feels their jobs can intrude on their lives 24 hours a day.

In the battle for talent, tech giants such as Google have become well known for perks, including free meals and “20 per cent time” when staff are free to develop their own ideas.

Other employers recognise they must become more flexible or risk problems with staff recruitment and retention. “Attracting and retaining talent has always been the lifeblood of any creative business. We are nothing without our people,” says Annette King, chief executive of Ogilvy Group UK, the advertising group, who explains how the company’s new office on London’s South Bank has more informal, collaborative workspaces, fewer fixed desks and wi-fi on its roof terrace.

“I’m glad millennials have forced us to rethink the way we work as the changes we’ve made to address their needs have benefitted all of us and made us stronger,” she concludes.