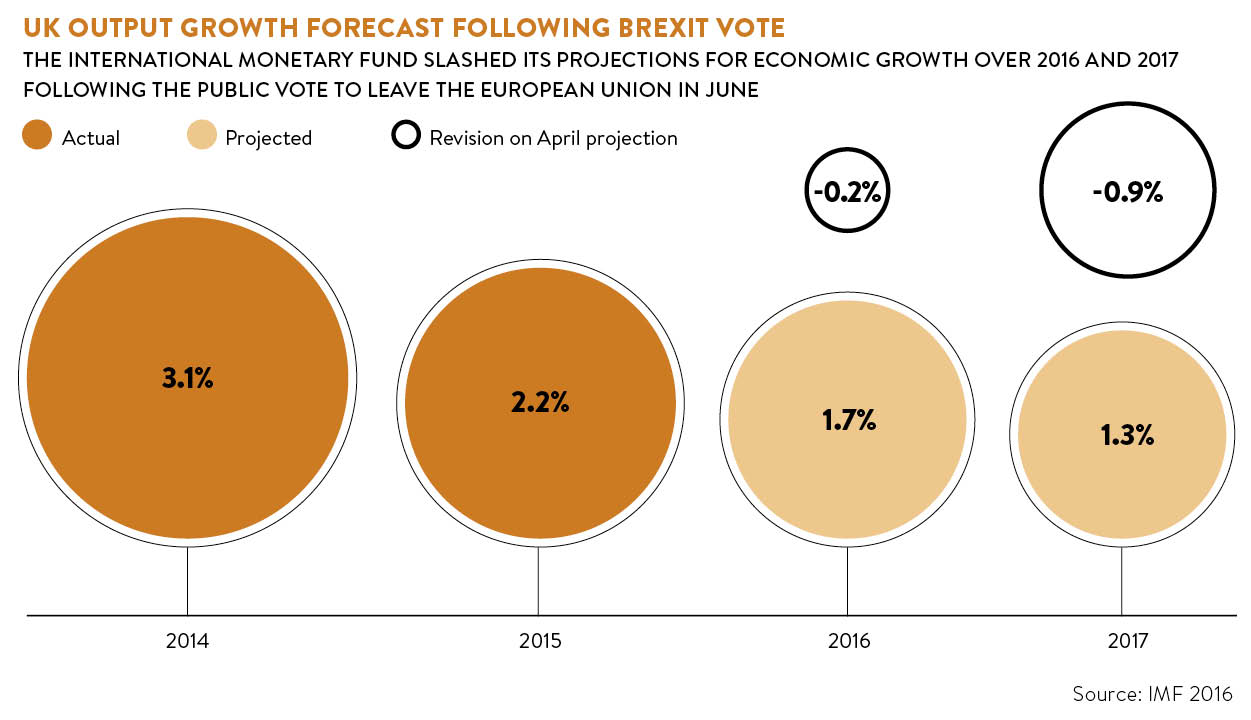

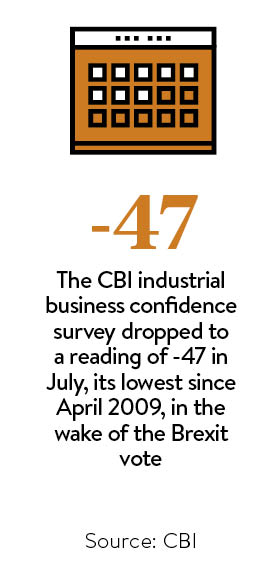

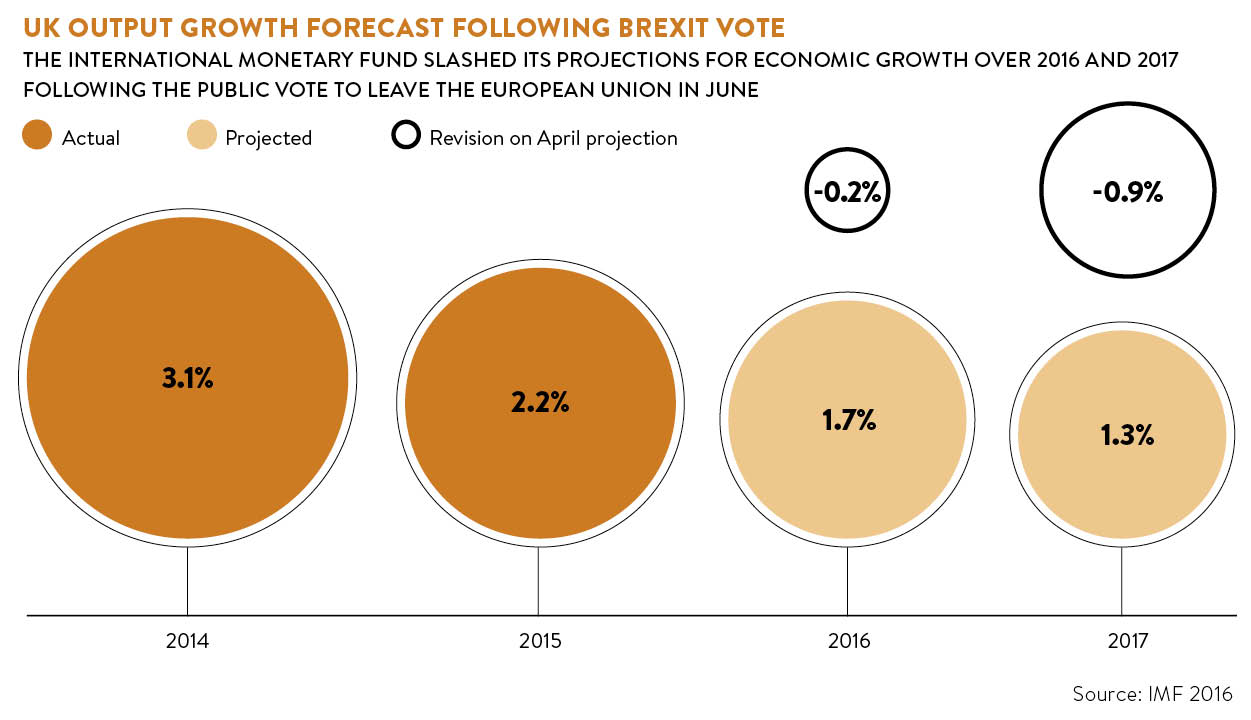

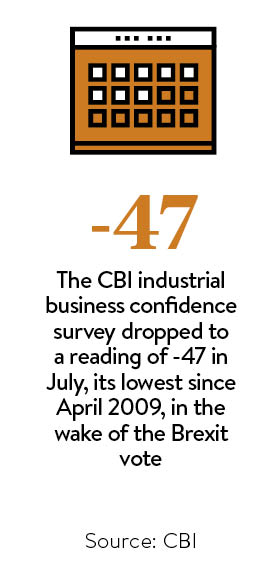

Has this country ever seen as much turmoil as in the weeks since the Brexit vote? The chaos is a matter of daily record. There’s been an immediate economic hit, which prompted the Bank of England to drop interest rates to 0.25 per cent, investment is stalled and confidence is falling. It seems unprecedented, but is it? Looking back to 2007-8 and the financial crash, it seems like things have been a lot worse.

A quick recall: September 2007 saw a run on Northern Rock bank, which was subsequently nationalised in February 2008; September 2008, HBOS was rescued by Lloyds after a share price crash; and in October the government was forced to bail out the Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds TSB and HBOS, all leading to an economic slump that the country is only just seeing the back of.

With Brexit, there are signs that things may not be so bad. Tourism has benefitted from the falling pound with 4.3 per cent more flights booked to the UK in July than the same time last year, according to Olivier Jager, chief executive of travel research company ForwardKeys. Manufacturers are split with falls in confidence in London and the South East, but optimism in Yorkshire and Humber.

Crisis plan

So is Brexit worse than 2008 for the economy? And did we learn anything from that crash that might help business prepare for these troubled times?

“The main difference between 2008 and Brexit is the level of uncertainty,” explains James Driver, communications manager for the Association of Project Management. “In 2008, things happened suddenly and quickly. With Brexit, there’s a limbo effect. People aren’t investing and businesses aren’t sure what’s going to happen.

“What 2008 did teach businesses was they should have a crisis plan. Back then, businesses had 2020 strategies and 2030 strategies so they knew how to expand, but had no real focus on what to do if something goes wrong. Now businesses have a plan B, and often a plan C and D.”

That varies from sector to sector, however. A recent survey by Logistics Manager magazine found that fewer than one in five logistics organisations had a post-Brexit plan ahead of the vote. Post-Brexit, there’s a test of the agility and resilience of global supply chain models, according to Gartner research director Lisa Callinan. While modern global supply chains should have the built-in logistics capacity to navigate and exploit disruptions such as Brexit, there are questions over areas like duties for UK-manufactured goods and manufactured goods from the European Union, which remain hard to plan for.

To some degree, says payments fintech startup Klarna’s co-founder and chief executive Sebastian Siemiatkowski, the finance and retail world is so different from 2008 that Brexit’s tariff effects may be minimised.

“What’s happened historically is that duties are used to make trade harder – which makes trade harder,” he argues. “These days there are solutions that can allow you to buy an item direct from a factory in China, which can give you a price upfront that includes all the necessary paperwork and will still be cheaper than a high street store. I don’t think that anything any government does right now will be able to stop this trend.”

Karen Briggs, head of Brexit at KPMG, previously worked with the consultancy’s banking and finance sector clients, and says financial services learnt a great deal from the 2008 crash, but other sectors have some catching up to do.

Companies need to consider a variety of scenarios based around the possible changes to the ‘four freedoms’ of goods, services, people and capital

“The Bank of England had done a lot of contingency planning,” she explains. “In fact, banking and airlines face similar issues with the City worried about the EU banking passport while airlines are concerned about access to the European Open Skies agreement. Airlines are going through the kind of questions banks are a little more prepared for.”

For Ms Briggs, the other key affected sectors are those with cross-border supply chain logistics, such as automotive, sectors that sell heavily into the European market like pharma and sectors reliant on consumer confidence as the pound falls. Companies need to consider a variety of scenarios based around the possible changes to the “four freedoms” of goods, services, people and capital, she says.

For Ms Briggs, the other key affected sectors are those with cross-border supply chain logistics, such as automotive, sectors that sell heavily into the European market like pharma and sectors reliant on consumer confidence as the pound falls. Companies need to consider a variety of scenarios based around the possible changes to the “four freedoms” of goods, services, people and capital, she says.

Exit strategy

In some cases, and unlike 2008, one option is an exit strategy. EasyJet, for instance, has opened talks around moving its headquarters from the UK to secure an EU air operator’s certificate while Ireland-registered Ryanair is pivoting its investment, new planes and growth plans into the EU. Nissan chief executive Carlos Ghosn is delaying investment decisions around the company’s Sunderland plant pending single market negotiations. “Most of the production out of Sunderland is exported to Europe so obviously for us the relationship which is going to prevail between the UK and Europe is very important,” he says.

For IBM’s UK and Ireland chief executive David Stokes, the key to stopping a similar tech drain is based around three essentials: retaining access to the digital single market, remaining part of the EU-US data transfer pact, and ensuring investment in domestic innovation and research remains at EU levels.

IBM’s new Brexit Transformation Lab, based at the company’s UK headquarters in London, is offering clients “trigger for transformation” consulting workshops focusing on financial services initially.

“Watson [computer system] works through social sentiment, and the 80,000 pages of laws and regulations that encompass the UK-EU relationship to help understand when, where and how much any impact or opportunities are likely to be,” says Phil Hussey, IBM’s Brexit business development leader. “On the one hand, we don’t know what we don’t know, which is why most people are doing more listening than talking right now. On the positive side, looking hard at your business post-Brexit can lead to valuable changes.”

And the key to making those changes work lies with the referendum’s most controversial issue – people and freedom of movement. On the one hand, for a business, agility is key, argues Chris Copeland at digital workforce consultancy Betterworking. He says considering alternatives to the traditional physical workplace from hot-desking to home and remote working, opportunities to build more flexibility into workforce planning, making work agnostic to where, when and by whom it is done.

But Ms Briggs points out that huge uncertainty over whether EU nationals will be forced to leave the UK and UK nationals forced to leave the EU is damaging workforce confidence, which can hurt productivity.

The Association of Project Management’s Mr Driver agrees. “2008 showed how lean businesses had an advantage,” he concludes. “Interim hiring – putting staff on contract as opposed to permanent jobs – proved an effective tool. However, failure to nurture those staff – cutting back on training, for instance – damaged the long term. Areas like training need to be reinforced rather than cut back. At the end of the day, it’s your people who will make the difference between Brexit being a crash or a great opportunity.”

Crisis plan