Agile thinking, while not commonplace in UK boardrooms today, is expected to become the basis of the management practice of tomorrow.

The approach is already being taught on a number of management training courses. But outside academic spheres, it is also referred to under various other monikers ranging from customer centricity to faster, smarter and leaner.

This is about responding in a swift and imaginative way to the accelerating business change being brought about by technology and digitisation. But to do so frequently involves behaving in counter-intuitive and counter-cultural ways.

For example, in a fast-moving world, agile thinking means abandoning the traditional annual plan, with its reassuring key performance indicators, to create small, quick-and-dirty projects that deliver often imperfect products instead. These products can be killed if they do not work, but also have the potential to deliver rapid benefits.

At the heart of this approach, however, is what Simon Hayward, chief executive of leadership development consultancy Cirrus, describes as the “agile leadership paradox”.

“Being able to respond to change is vital, but the paradox is that you have to be willing to be a disruptor and almost undermine your own thinking by challenging it and looking at how it could be knocked sideways,” he says. “The point is you’re either going to be on the front foot changing the way your industry operates and creating competitive advantage or you’re going to be responding to that.”

Some pioneering organisations beyond the rarefied world of technology startups have already embraced agile thinking and applied this philosophy across the enterprise. But the majority are still either in the process of working out how to do it or have introduced the approach into their IT and digital departments only, which is simply not enough.

Vikram Jain, managing director of agile management consultancy JCURV, explains: “The problem is you end up with a two-speed business. So an internal customer will say they want something; IT designs, develops and tests it in an agile way and other departments, like marketing and legal, use a traditional waterfall approach to launch the solution, which means it gets stuck in a bottleneck.”

What is required instead are cross-functional teams that are “co-located and empowered to solve problems and ‘fail fast’ without hierarchies getting in the way”, he says. Failing fast is about cutting your losses when something is not working and quickly trying something else.

But the challenge involved in going down this route is that most large organisations still operate under a command-and-control style of management, which is based on a “fundamental belief that you can’t trust people to do the right thing”, says Mr Jain.

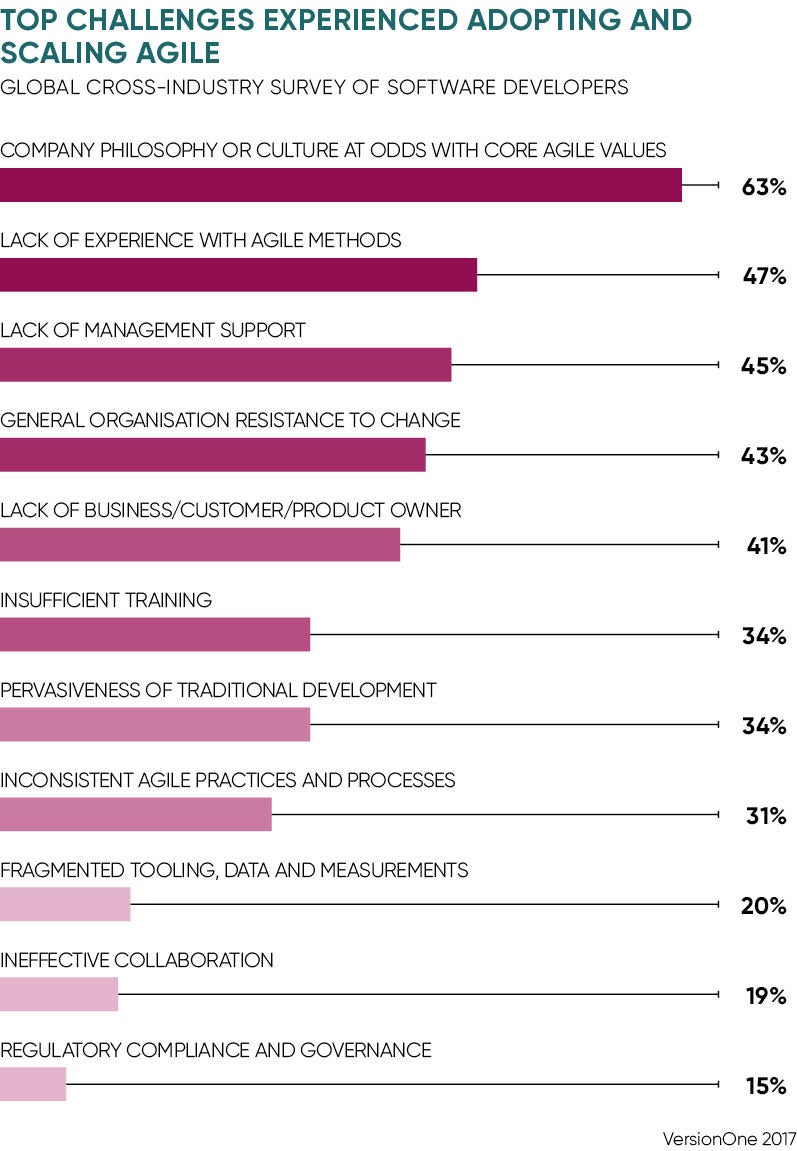

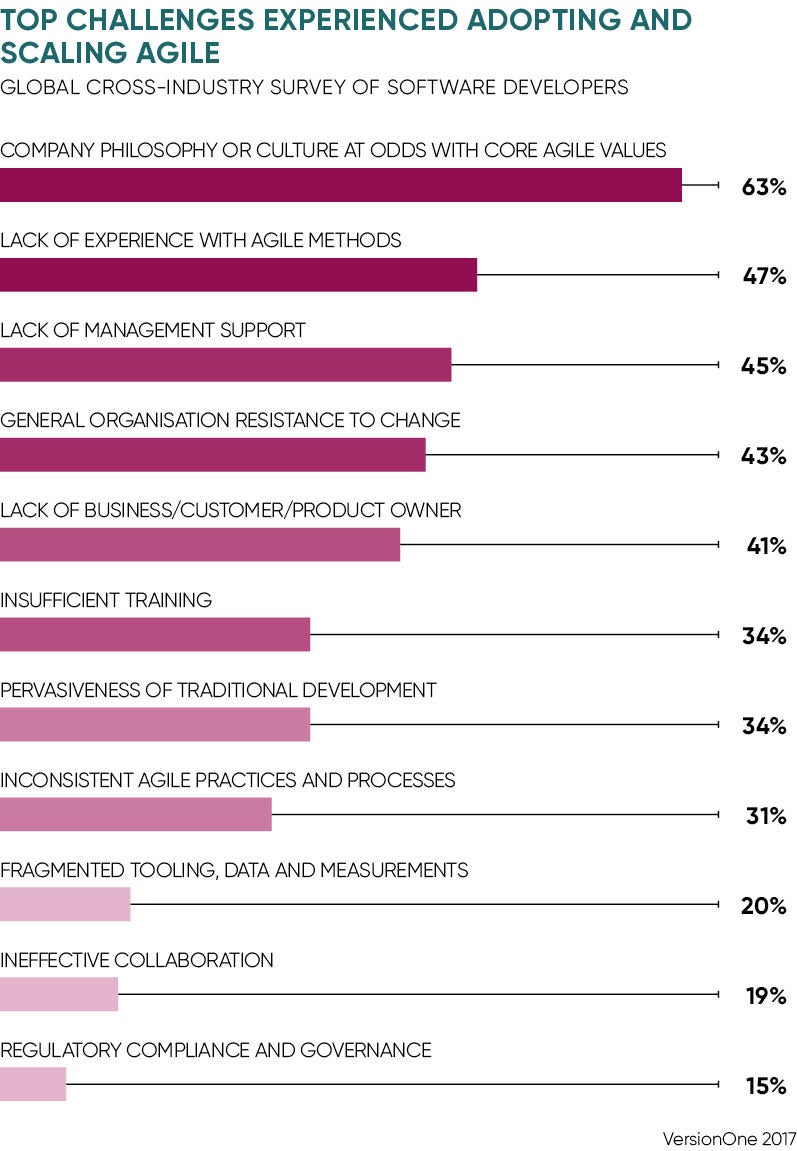

Other barriers to agile ways of working include company silos that inhibit collaboration, deferential and bureaucratic processes, and an inability to prioritise, all of which slow change down.

One of the central principles of agile is that teams get on with it and self-manage

“At the heart of all this is control,” Mr Hayward points out. “One of the central principles of agile is that teams get on with it and self-manage. Most senior leaders find it difficult to cede control to others, especially if they’re trying to drive change, but if they can devolve decision-making to the lowest level, it’s very empowering.”

A key challenge here though is the majority of senior leaders employ management techniques that have proved successful in the past, but are largely unsuitable for addressing today’s problems. But because they do not know how to change, they end up focusing too much time and effort on the wrong things.

“The biggest barriers to agile are cultural and behavioural, and it starts from the top,” Mr Jain says. “If you don’t appreciate that ways of working need to change, you’ll put up barriers to others doing it too.”

Put another way, to adopt agile thinking, it is vital that senior executives change their own belief system and attitudes. Mr Hayward explains: “It’s about rethinking your beliefs and developing ‘learning agility’ to create a climate where people can operate effectively. This means not blaming them if things go wrong, but encouraging them to learn from their mistakes and take responsibility for their actions.”

Although it is widely acknowledged that changing attitudes is one of the hardest things to do, there are various possible options that can help. Management training organisations and tertiary education institutions, such as the University of Central Lancashire, offer a range of programmes, for instance, and there are also plenty of books on the subject.

But another useful approach is for senior leaders to spend time with peers at companies that have already gone down this route, or even with members of their own IT department, to see for themselves what this new way of working looks and feels like.

As Nicolas Minvielle, head of Masters in marketing, design and creation at the Audencia Nantes School of Management, says: “You need to spend time with people who know about it. Otherwise it’s just a story and won’t mean much; you certainly won’t change your behaviour as a result. So you need to go out into the field and live it to truly understand it.”

But this change in behaviour from the top is crucial if agile thinking is to become embedded throughout the organisation. On the one hand, it is up to leaders to create a safe environment that enables team members to work in an agile fashion despite pushback from elsewhere.

On the other, says Mr Jain: “Leaders need to start leading again, which means two things in practice: defining the vision and shouting about it, and then, as their teams become more empowered, stepping back and spending time removing any impediments to their success and effectiveness.”

While small benefits should make themselves felt quickly, embedding agile thinking into how the organisation operates is likely to be a 12 to 24-month process.

“It’s not a short-term fix,” Mr Hayward concludes. “The thing with agile is that it takes time; it’s such a different way of working and requires such a different mindset because it flies in the face of much traditional management practice and culture.”