A lot has changed in 20 years. In 1995, we didn’t have the internet – certainly not at a consumer level – let alone broadband or cloud applications, so business moved in nice predictable cycles. People didn’t expect much and company life was good.

Then digital punched a hole through the picture. Overnight people could shop without going outside, talk to friends in New Zealand for free, not run out of camera film on holiday, give up the commute and generally do everything much, much faster.

The late-1990s were, therefore, a manic period in our history. Old companies debated how to respond to the situation, whether to stick or twist. Should they join the crazies and buy a load of startups or resolutely resist what was surely a phase? New companies raved skittishly about all the possibilities.

Responding to change

This was the birth of agile, though we didn’t know it. It was the first time in a long time that businesses had to respond to a change so fast and profound. The genie roared out of the bottle and ever since chaos has reigned supreme.

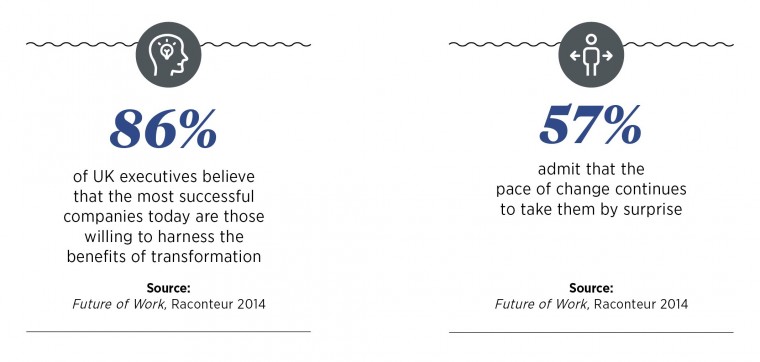

Since the turn of the century executives in slow-moving organisations have sat nervously on the edge of their seats, wondering when a new invention will come along and eat them.

In this era, “disruption” no longer describes an annoying happening that gets in the way. It moved to the positive sense, to push things forward and shake up tired formats.

To be fair, a lot of brands have coped admirably with all this turmoil and even thrived, either by adapting to the new changeable landscape or by buying companies that could do the job for them. Ones that shut their eyes and hoped it would go away have by now shut their doors too.

Retail was hit particularly hard. Game, Woolworths, Blockbuster, Comet, Land of Leather, Borders, Zavvi and JJB Sports all flat-lined. In a single year, 2013, HMV, Jessops, Blockbuster, Republic, Dreams and Dwell all either went into administration or shut down for good.

When people talk about agility, they are not referring to the changes a business makes, but the structure that allows it to move quickly should the need arise

The credit crunch didn’t help, but these businesses collapsed because of an inability to adapt, not because of a lack of liquidity. Responding to the swirling, frothing market has been front-of-mind for chief executives ever since – one wrong move, or failure to move, and you’re toast.

Revamping business structure

“Agile ways of working are a response to working in more complex situations,” says Aaron Shields, head of strategy, Europe, the Middle East and Africa, at FITCH retail and brand consultancy.

“With a connected world and a myriad of channels to buy and sell from, it seems everything is a lot more complex than it used to be. So agile ways of working are being adopted by airport authorities and design consultants alike.”

When people talk about agility, they are not referring to the changes a business makes, but the structure that allows it to move quickly should the need arise. In theory it’s possible, though unlikely, to be agile but not change things for years on end.

Whatever the definition, today everyone’s at it, to the extent that even the companies which started the ball rolling in the nineties and noughties are reinventing themselves to avoid becoming ten-year-old fossils.

Yahoo has undergone dramatic changes in recent years, Cisco has just appointed a new chief executive to take the business in a different direction and Google, the undisputed champion of agile, recently decided its logo needed a spruce up.

Companies that inflated to epic proportions and shrivelled in less than a decade are too numerous to name. Many were purchased in astronomical deals by corporates that had no idea what to do with them, perhaps hoping they would provide residual income forever and mothballing them when this didn’t happen.

Embrace new technologies

For the rest, the key to surviving the agile era will be customer interaction, data collection and actionable insight. Knowing your customers has always been important, but now the information comes faster and is more detailed. Chief executives are motivated by the thought that rivals are acting on insights before they get up in the morning.

“Threats will arise through IT-enabled product enhancements, improved customer connectivity, especially through personalisation, supply chain efficiencies, connected devices or crowd-based business models,” says Phil Freegard, a partner at Infosys Consulting.

“It is time to let go of sentimental ties to legacy systems and embrace new digital alternatives. Speed and customer understanding will be key if entrenched businesses within sectors like banking and retail want to survive the digital shake-up.”

Cloud is another weapon of choice, with its capacity to bring disparate teams together for coherent action, says Ian Stone, UK and Ireland managing director at Anaplan, a software company.

“The on-demand resources of the cloud provide businesses with unprecedented scale, and the ability to manage and process data volumes cost effectively that were previously unthinkable,” he says.

“To borrow an example from the world of rugby: when you are camped on the opposition’s try line, you want to recycle the ball quickly so you can maintain your competitive advantage – playing a slow ball gives the opposition the time to get back into shape.”

It’s hard to see how markets could ever go back to the old way and be anything other than confusingly fast changing from here on in. The best advice is to hold on to your hats, it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

CASE STUDIES

Success: Trainline International

Trainline is a leading name in the UK travel industry, offering reduced prices on train tickets online since 1997. To replicate its success in the UK across the European market, the company launched an agile startup business called Trainline International under the Trainline umbrella group in 2012.

The international venture took inspiration from Eric Ries’s influential lean startup model, which was implemented within the support framework of the main Trainline company.

The international venture took inspiration from Eric Ries’s influential lean startup model, which was implemented within the support framework of the main Trainline company.

This approach allowed Trainline to grow rapidly internationally while still keeping costs low. The team’s initial strategy was to offer a minimum viable product, which could be easily adapted for nuances of the new regions.

It adopted a mobile-first strategy, incorporating mobile-friendly designs, which meant they could access new users quickly. Elastic cloud development was also crucial to update the product continually in response to customer feedback and requests.

In order to meet the high standards the company required quickly, it used freelance content creators they found through online talent marketplaces such as Upwork. They initially used freelance workers for marketing purposes, but eventually expanded this approach more broadly to include technical projects.

It enabled Trainline International to scale quickly by engaging talented independent professionals with the specific skills needed for each stage of growth as business needs evolved – no large overheads and little waste.

The flexible, hybrid approach has allowed Trainline International to grow fast. The company now services 11 countries across Europe two years after launching. As a result of its success, this approach is now being adopted within the parent Trainline business, where utilising freelancers is an important part of the company’s competitive strategy.

Failure: Blockbuster

The conventional wisdom says digital content distribution channels destroyed Blockbuster. All of a sudden people were streaming or downloading films from the internet, or at the very least having DVDs sent to their door, rather than walking into a real shop, browsing and selecting.

But it was really just a general failure to move with the times. In the early-1990s box office receipts fell, which had a ripple effect on activity at Blockbuster stores. The business reacted by expanding its offering, stocking more toys and sweets.

But it was really just a general failure to move with the times. In the early-1990s box office receipts fell, which had a ripple effect on activity at Blockbuster stores. The business reacted by expanding its offering, stocking more toys and sweets.

This, many experts think, was not the right response, or at least there should have been more responses. If fewer people wanted to rent videos, then fewer people would also buy food. In 2000 came the crunch – a single poor decision that effectively spelled the end for Blockbuster.

That year the business was one of the biggest names in film, dominating the market for rentals and boasting thousands of shops, serving millions of customers around the world.

So it was a gutsy Reed Hastings who met Blockbuster executives to propose a joint venture. Netflix, his small business, would run the online side and Blockbuster would promote Netflix with marketing material through its stores. The deal was never done. Blockbuster crashed in 2010, while Netflix is now valued at more than $30 billion.

Responding to change