As the number of communications channels grows, so does the scope of an organisation’s communications strategy. In the 1980s you had a straight choice between talking face-to-face, speaking on the phone, sending a fax or telex, or writing a letter.

Strategies were, therefore, pretty bare bone – use your company phone because there is no alternative, be polite to customers and partners, and when you want something to be recorded or remembered put it in writing.

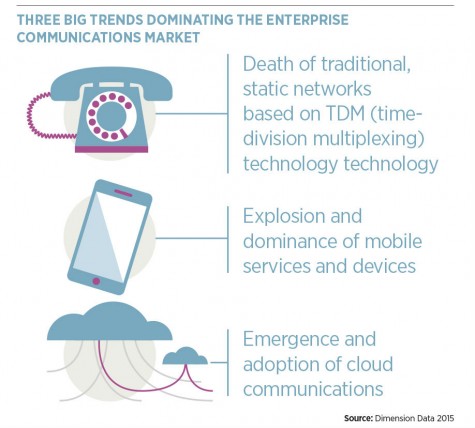

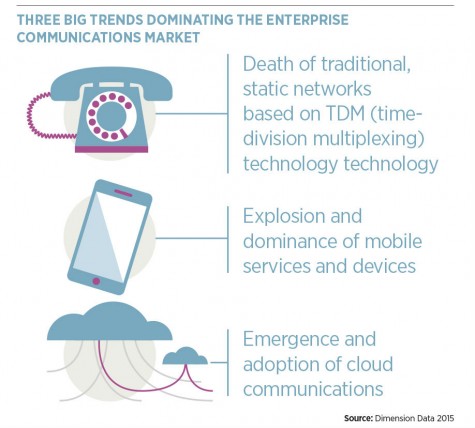

In the last 30 years those limited options have sub-divided like amoeba and ballooned into a million different options for text, voice, images and video. Better, faster networks have opened up opportunities for new devices and services, which in turn have fuelled the latent wanderlust of cooped-up desk jockies.

Now the average large company will have employees scattered across the world, some in offices, some in the field – some perhaps even in a field – as well as different time zones, varying infrastructure, language barriers, the lot.

But organisations are required to help these people communicate with each other as well as third parties fluidly, securely and meaningfully in real time. People are everywhere, technology is limitless, competition is rife, so a brilliant and holistic strategy is required.

Your average common-or-garden communications strategy is a complex thing, but for large businesses such plans are truly multi-dimensional

The situation is creating a natural contradiction, however. Strategies must be sophisticated enough to cover the myriad of adopted communications channels and how they are used, but simple enough that everyone in the organisation can understand what’s going on.

Communications are a more important component of a smooth-running business than ever before and, annoyingly for anyone trying to get a job done, there has never been so much scrutiny of what is being said. The news is full of social media slip-ups, texts gone awry and notepads photographed from 50 feet by eagle-eyed paparazzi photographers.

Adding to the headache for those responsible for envisioning a strategy is the fact that this great big mess is moving around all the time, like a massive multi-layered trifle carried by a tipsy waiter. Executives have to somehow account for its movements and load future changes into current plans.

Your average common-or-garden communications strategy is a complex thing, but for large businesses such plans are truly multi-dimensional. Have you considered, for example, that a plan should reflect the psychological impact of employees who become remote workers, parted from their colleagues?

Your average common-or-garden communications strategy is a complex thing, but for large businesses such plans are truly multi-dimensional. Have you considered, for example, that a plan should reflect the psychological impact of employees who become remote workers, parted from their colleagues?

Remote working has its obvious advantages, but so does being surrounded by a familial tribe of like-minded workers, with whom you can share your successes, snipe quietly behind the boss’ back and go for a pint at clocking-off time.

“Many of us work in disparate, geographically remote teams. The obvious downside of this is a loss of rapport between employees,” says Garry Veale, president of Avaya in Europe. “While communication technologies have done wonders to plug the geographical void, they haven’t always enabled collaboration within the office. A great unified communications strategy takes this social need into account.”

Indeed, flexible patterns have become so normal that it’s weirder to work nine to five, Monday to Friday. People don’t do inverted commas with their fingers anymore when they say they’re “working from home”, so company systems, networks and processes should grow up a bit too.

“Remote working is no longer the exception to the rule and businesses need to centre on the best talent, no matter where individuals are located, rather than on who is within reach of a physical office,” says Graham Bevington, executive vice president at Mitel.

“With the massive diversification through which companies share information, securely and reliably, they need to be agile enough to cope with the demands of employees, partners and suppliers alike.”

Companies are dealing with this in different ways, according to Mr Bevington. For example, some have created an extension to the bring your own device trend by allowing employees to choose from a range of approved devices which are secured in-house and linked up to company networks.

Approaches to software are changing too. New apps, for example, are cheap, easy to access and designed to work without the need for training. Some agile businesses have stopped contesting their use and have accepted the best apps into the fold, including them in workflows to create results.

“A consistent and standards-based communications strategy is important for companies to ensure they fully realise the efficiencies that technologies such as cloud and software as a service can bring,” he says. “These are keeping their architectures flexible, able to embrace new applications, devices and technologies quickly.”

Paul Leybourne at Vodat International believes the hardest thing about creating a strategy is that new technologies evolve quickly. Strategies hoping to encompass them should therefore accept change and account for it, and not even attempt to predict the nature of it.

“It’s important to future-proof a strategy, but technology and social trends are advancing so quickly it is impossible to second guess what they will look like in 12 months let alone five years, which would be the typical time to write down capex [capital expenditure] investment,” says Mr Leybourne.

“So it’s important to adopt a flexible approach. As an example, companies moving to hosted virtualised platforms can usually scale up very quickly, which is much better than trying to size servers and connectivity that could quickly become redundant if the sizing exercise is underestimated.”

HOW TO DEVISE A COMMS STRATEGY

If you’re unclear how to create a strategy, then here’s a helping hand. According to experts, the document should define what is adopted by the company, why and for whom. It should create a timeline for adoption, and include details for training and “selling” of the new technology to staff so they don’t revert to the old methods.

Most importantly, it should be aligned to the needs and goals of the organisation. It should outline details for a bespoke experience, not a borrowed facsimile of some other company’s plans. Ideally, it should be supported by evidence of tests on small focus groups. And it should be easy to understand.

“When defining a strategy it is imperative to ensure support from management for not just the cost of purchasing, but also the adoption across the organisation,” says Nigel Dunn, managing director of Jabra UK and Ireland. “A clear communications strategy within organisations is vital for the growth and success of that company.”

Julian Gorham, head of brand for Gather, says company public relations around the strategy must be stripped back. “Organisations have far too many words around them. One FTSE 250 company proudly told me recently they had ten values. I can’t remember the names of ten friends let alone ten values.”

So we’re back to that nasty puzzle again, taking something that is vastly complex, and condensing it into a set of written principles and actions that are easy to grasp.

It’s a rabbit out of the hat trick alright, but companies that pull it off will enjoy a distinct advantage in this modern, agile world than those that do not.

HOW TO DEVISE A COMMS STRATEGY