Speak to a technologist about collaboration and they’ll tell you about social media – the Facebook and LinkedIn lookalikes inhabiting so many corporate systems, carried wherever a worker happens to be.

It wasn’t always like that. The 1970s wasn’t actually that long ago, but in technology terms it feels like the dark ages; the fax machine was just starting to allow sharing of documents across the globe and, if you were very lucky, you might be sitting in front of a computer rather than an electric typewriter.

Things have changed drastically now – or have they? IT business Daisy Group commissioned research that suggests a lot of companies are stuck in the eighties and nineties. Some 61 per cent were still using large filing cabinets, 46 per cent use a fax machine to send documents rather than attaching them by e-mail and floppy disks are still in use. One in ten still encourage their staff to use a business card box to manage their contacts, while just 3 per cent were allowed to use wearable technology. The findings were from a 2,000-strong poll, so they are significant.

There is, then, some way to go in terms of adopting newer technologies, which is lamentable because when circumstances dictate they should be used, the results can be striking.

John Maher, director of learning and information services at Scotland’s University of the Highlands and Islands, says: “Our primary use has been video-conferencing.” This is essential as Highlands and Islands is a federation of colleges spread around the region, so face-to-face meetings are not always possible. “We have around 200 studios dotted around the Highlands and Islands, so that covers about a sixth of the land mass of the UK,” he says. “We can connect groups of students together in large cohorts and deliver curriculum that they wouldn’t have access to from their normal location.” This means people who don’t want to go to urban universities don’t have to.

We want to communicate in the same way as before, but there have been some changes in how we’ve evolved the technology and our uses of it

Technology has to be robust. There are around 160 connections an hour at peak times and domestic internet, although useful as an alternative when the students can’t get in, doesn’t generally have the bandwidth. The academic and administration teams also use video-conferencing for occasions on which getting together would be difficult.

High-definition screens have helped students and staff engage, he believes. People who aren’t used to video-conferencing often take a while to settle into it, but in general the facilities are helpful in themselves. The system allows for split screens so the tutors can have a look at all the participants at once and check for anyone whose attention is wondering. Initially, explains Mr Maher, the screens were standard resolution so things have become easier. “Now it’s a crystal-clear picture, so you get very good visibility of what’s going on in each of the studios.”

At the same time, the old-fashioned “chalk and talk” lecture style is giving way to a more interactive model. The human side is changing to adapt to what’s technically possible.

[infographic]

This change isn’t always positive, suggests Dave Coplin, chief envisioning officer at Microsoft, who is the author of two books, Business Reimagined and The Rise of the Humans. “We essentially want to communicate in the same way as before – our need to communicate hasn’t changed,” he says. “But there have been some changes in how we’ve evolved the technology and our uses of it to do that.”

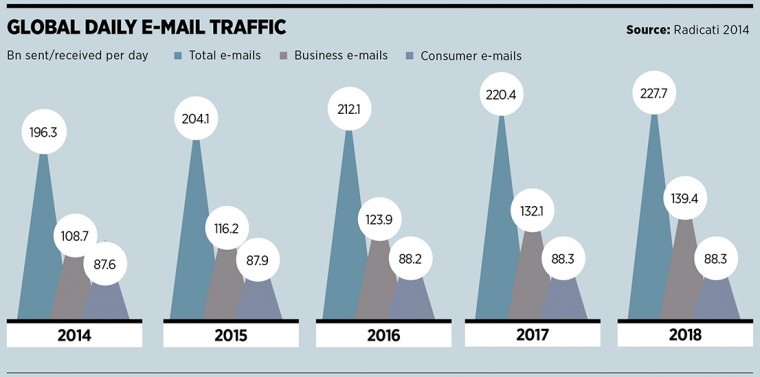

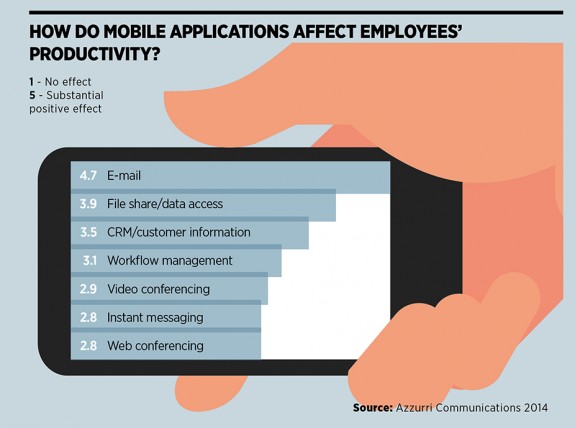

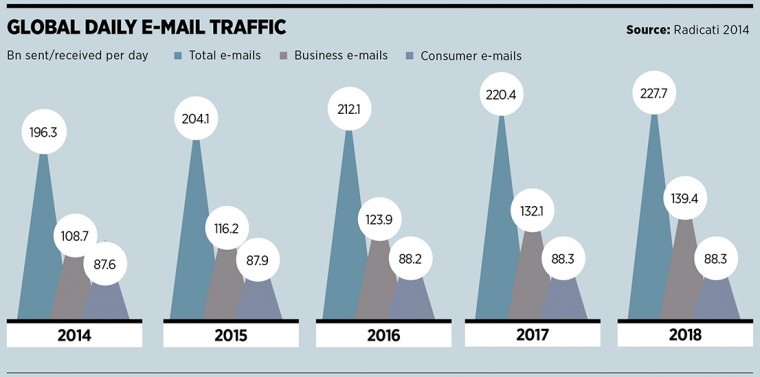

The rapid changes we’ve seen have involved, for example, the jettisoning and deriding of e-mail by many commentators, but Mr Coplin suggests it’s still a great mechanism for asynchronously communicating concepts to specific individuals.

“That’s as true a need today as it ever was,” he says. “The real challenge is that when we turned up 30 to 40 years ago and duplicated that analogue process of communication called the office memo, made it faster, better and cheaper, and turned them into e-mails, we never asked ‘Hang on, do you need to communicate that way?’ So we accelerated an old way of working and made the problems of working with it much worse.”

One organisation uses collaboration to respond to customers and is reporting a 50 per cent lift in productivity

In other words, we made the office memo easy, but there wasn’t much in the way of an “off” switch, so we’re now deluged with unwanted mail. What Mr Coplin would like is a more appropriate use of different communications media and that’s what we haven’t learnt yet. “In an age where I have a multitude of different ways of communicating and I can choose what’s the most appropriate way to communicate a particular message to an audience I need to reach, just banging something out isn’t appropriate,” he says.

A side effect of the poor use of the technology is a less-focused person, he suggests. We now have so many communications that we never get to the end of it. Some of Mr Coplin’s research suggests that 77 per cent of the UK workforce thinks a productive day at work is one spent clearing your e-mail in-box. “Our brains like that, they give us dopamines and whatever, but e-mail is a process of work that pushes messages around, not the work itself,” he says. Another issue is that an alert about an e-mail, the Facebook message, whatever, can be as distracting as the message itself, so the process takes up even more time.

Facebook and its competitors are relevant in a business setting because the most recent iteration of corporate communications technology is the social construct. Offered by Microsoft through Yammer (an acquisition), Slack, Podio and others, it consists of a social media lookalike through which companies can collaborate.

[embed_related]

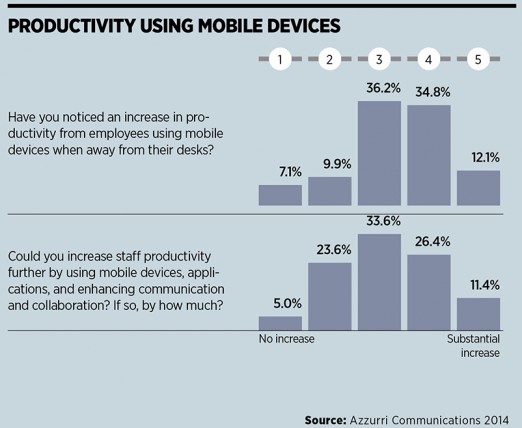

Strategist Kathryn Everest, communications and collaboration solutions at Jive Software, confirms that clients are reporting solid productivity increases. “One organisation uses collaboration to respond to customers and is reporting a 50 per cent lift in productivity. Some others are using it to improve innovation; others are having challenges with employee retention and they focus on that objective, experiencing 10 to 20 per cent increases,” she says.

The fax may still be in use, but by now it has to be fading. The emphasis now is to get whatever means of communication the user wants – e-mail, text, voice, social – on to the gadget of their choice, whether it’s provided by the office or their own. This enables working when and where they want, which in turn pulls a refresher of management skills through the door.

So, what’s coming next? People have different ideas inevitably. Mr Coplin would like to see more appropriate technologies applied to different tasks and the issue there is the communicator rather than the gadget. Consumers are choosing their gadgets under policies called bring your own device (BYOD) and the underlying software can forward calls and messages at will.

Ms Everest believes it’s going to become even more ubiquitous. “Right now to some degree ‘social’ is becoming a feature. People are building products and adding social. I don’t think it’s a feature, I think social and collaboration need to be there from the ground up – it’s personal and people-centric, so it’s going to get even more personal. The technology is going to get better at knowing you because you’re contributing to it – it will know what you’re interested in, how this changes over time and will become more of an assistant.”