The development of the UK’s food system since the Second World War is in many ways a story of unqualified success. Policies in the post-war decades to increase production and liberalise trade have meant the vast majority of the population can access high-quality, low-cost and safe food at a time and a place that suits them.

In the process, the sector has developed into a key pillar of the UK’s economy. Food and drink is the country’s largest manufacturing sector accounting for 16 per cent of total manufacturing turnover and providing employment for more than 400,000 people, according to the Food and Drink Federation (FDF).

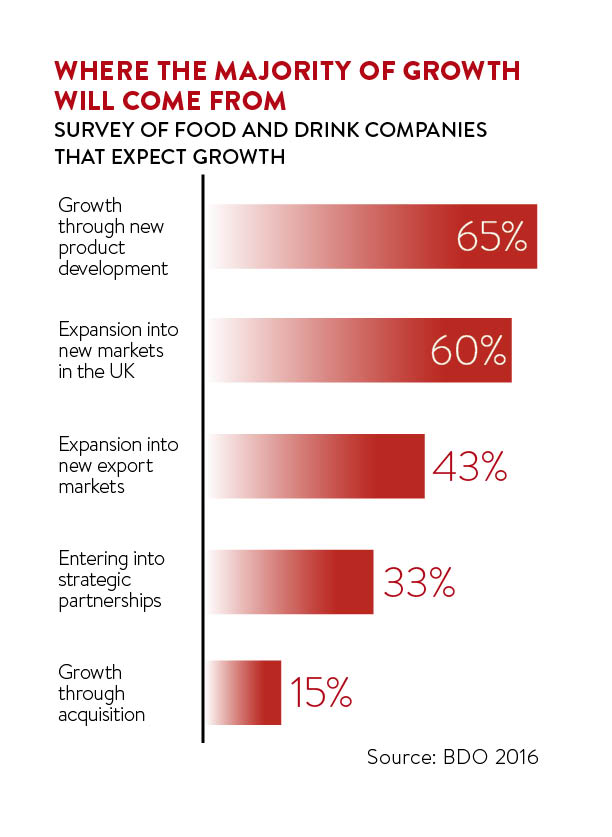

The food industry is seen as having huge potential for future growth. The FDF is five years into a plan to grow the manufacturing sector by 20 per cent up to 2020, while analysts at IGD forecast the UK grocery retail market will reach £203 billion by 2019, up more than 16 per cent from 2014.

Unprecedented change

Perhaps more than in any other post-war era, the past ten years have seen a fundamental reshaping of the food industry as changes in consumer demand, the rapid adoption of new technologies, and emerging social and environmental challenges have placed fresh demands on businesses operating across the entire supply chain.

These changes have arguably been felt most acutely in the retail sector where the growth of online shopping, in particular, has forced supermarkets to rethink business models built around large bricks-and-mortar estates. With IGD predicting online to be the fastest-growing grocery channel between 2014 and 2019, competition is set to remain fierce, even more so following the recent arrival of Amazon into the online grocery space.

The hegemony of the big supermarkets has also been threatened by the emergence of discount grocers, most notably Aldi and Lidl, whose popularity has soared as consumers are attracted by their keen prices, tight ranges and good-quality produce.

Rapid growth of discount grocers Lidl and Aldi have forced the Big Four supermarkets into an ongoing price war

The growth of the discounters has resulted in the waging of a seemingly perpetual price war between UK grocery retailers that has had a knock-on effect along the supply chain with margins squeezed and even well-known brands facing the threat of delisting.

A number of British manufacturers have sought to strengthen their balance sheets either through acquisitions or by inviting inward investment from countries such as China. Others have looked to spread their risk by building a successful export business with entrepreneurial companies such as Innocent, Dorset Cereals and Ella’s Kitchen enjoying growing demand for their products overseas.

There has been consolidation too in the wholesale sector with major players like Booker acquiring smaller rivals in a bid to achieve greater economies of scale and provide better deals to independent retailers. The indies have themselves responded to the rapid expansion into the convenience sector of the big supermarkets by widening their ranges and introducing in-store services such as parcel collection.

The UK foodservice sector, meanwhile, is changing out of all recognition as disruptive players such as Just Eat and Deliveroo remove some of the barriers to eating out and in the process drive significant growth in the sector.

Food production

Farmers continue to feel the pressure from volatile commodity prices, particularly in dairy, where British producers are increasingly exposed to global market forces. One response from farmers has been to develop their own added-value products thus allowing them to achieve a greater margin. The UK’s decision to leave the European Union means farmers face an even more uncertain future while they wait to learn how subsidy payments currently received from the EU will be replaced, if at all.

In our dynamic, fast-growing food sector, a number of challenges have emerged that threaten the future sustainability of the food system. The relatively low cost of food has contributed to a situation where UK households throw away seven million tonnes of food every year, according to the Love Food Hate Waste campaign. Smarter packaging, which extends the shelf life of produce, offers one potential solution, but businesses agree that real progress on food waste will require collaborative action throughout the entire supply chain.

Consumption habits will need to change if we are to leave behind the legacy of a healthy, sustainable food system for future generations

A health time bomb has emerged in the form of the billion-plus people worldwide categorised as obese as a consequence of more sedentary lifestyles and a shift in Western diets towards more nutrient dense convenience foods. In the UK, the government considers the situation so serious it has set out plans to introduce a tax on sugary soft drinks to help curb consumption.

Awareness is also growing of the environmental impact of food production, with negative externalities ranging from the high greenhouse gas emissions involved in meat production to the effect on soil fertility of modern intensive farming methods. As well as technological fixes, such as the development of new precision farming methods aimed at maximising the use of scarce natural resources, there is a growing acknowledgment that consumption habits will need to change if we are to leave behind the legacy of a healthy, sustainable food system for future generations.

All of this means that, both by design and by necessity, the food systems of the future will look very different from those of the past and the present.