Historically, the requirement for local fixers to grease the palms of government officials and business associates to secure lucrative deals was seen as an accepted part of doing business in some foreign jurisdictions.

If any potential wrongdoing came to light by an agent working in a foreign land, company directors sitting on the other side of the world could comfortably deny all knowledge and safely escape censure.

But those days are gone. As novelist L.P. Hartley wrote: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” Jurisdictions across the globe are tightening up laws to eradicate corrupt practices.

The Bribery Act catches offences committed anywhere in the world by companies incorporated in the UK or carrying out any part if its business here

In the UK, the Bribery Act 2010 came into force with great fanfare in July 2011. It created a new offence of bribing a foreign public official and, most importantly for companies, a corporate offence of failing to prevent a bribe being paid on their behalf by an “associated” person.

UK Bribery Act

The offences and the extra-territorial effect of the act make it one of the most stringent anti-corruption laws in world, and have made it much harder for companies to turn a blind eye to bribery and corruption.

The legislation catches offences committed anywhere in the world by companies incorporated in the UK or carrying out any part if its business here.

Under section seven, a commercial organisation commits an offence if a person associated with it bribes another person with the intention of obtaining or retaining business or business advantage for that organisation.

Associated persons can be individuals or entities who perform services on behalf of the company, be they employees, agents or subsidiaries.

They could range from a sales agent giving back-handers to win commissions, a lawyer bribing a judge to secure an outcome beneficial to the company, or associates acting to speed up administration or secure favourable treatment from tax authorities.

Crucially, knowledge of the bribe on the part of the organisation is not required. Companies can fall foul of the law by failing to have “adequate procedures” in place to prevent bribery.

As David McCluskey, partner at boutique London law firm Peters & Peters, says: “It is intended to ensure people work as though they are sitting in central London, not central Africa.”

In emerging markets, such as Brazil, Russia, India and China, the risks in using local representatives or agents can be particularly high.

And corporates cannot afford to be complacent about it. In addition to huge fines and prison sentences, convictions could result in debarment from tendering for public sector contracts and disqualification from being a company director, not to mention the consequential reputational damage and loss of business.

A recent report from accountancy firm Deloitte showed that third-party failure could cause shareholder losses of up to ten times any regulatory fine and share prices to drop by 2.55 per cent.

Compliance

In recognition of the fact that no anti-bribery regime will be capable of preventing all offences, the act provides a full defence if a company can show it had “adequate procedures” in place to prevent bribery.

Adequate procedures are not defined in the act, but are the subject of government guidance centring around six principles: proportional procedures; top-level commitment; risk assessment; due diligence; communication, including training; and monitoring and review.

Companies have scrambled to put in place compliance regimes, which they hope will afford them protection from prosecution, if those acting on their behalf are caught out.

In reality, says Mr McCluskey: “It means having a visible and well-documented anti-bribery policy effectively disseminated to all staff and agents, a reporting hotline and procedure, with whistle-blower protection, and a hospitality register requirement.”

Every transaction now, says Jonathan Hitchen, partner at international law firm Allen Overy, contains anti-bribery warranties and termination clauses.

In some jurisdictions it is impossible to remove the risk by doing away with agents as in some countries having a local partner is required, notes Jeremy Cole, consultant in the London office of global law firm Hogan Lovells.

“The challenge when entering new markets is to check them [the local partners] out to see if they could cause harm to the company and expose it to criminal prosecution in the UK,” says Mr Cole.

Dan Hyde, partner at London lawyers Howard Kennedy, says: “Organisations need to examine the relationship with any overseas third party carefully and apply due diligence to ensure, as far as possible, they are choosing the right third-party representative and that the risk is not too great.”

Equally as important as looking at new intermediaries, adds Mr Cole, is the need to go back and look over historic relationships that may have been put in place under a less stringent regime.

The level of due diligence required, explains Michelle de Kluyver, counsel at Allen & Overy, is risk-based and will depend on the jurisdiction and nature of the deal.

Jurisdictional risks

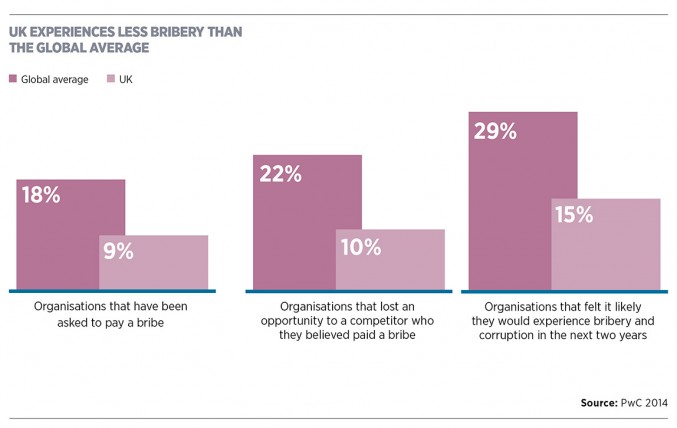

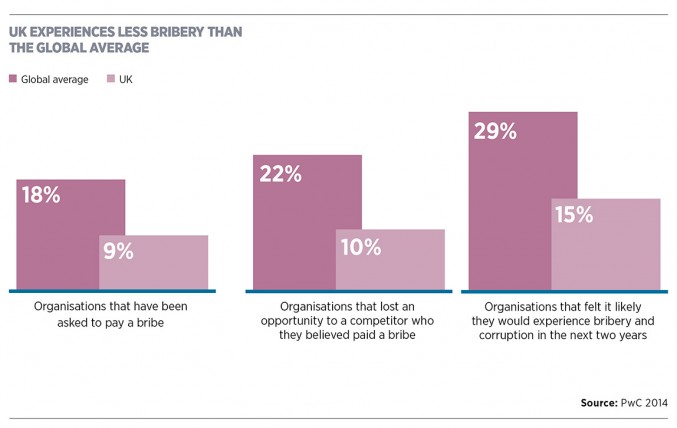

Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index is a guide to the jurisdictional risks. It ranks countries and territories based on how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be. In the 2014 table Denmark comes out as the least corrupt country, while at the bottom of the list, ranked in position 174, is Somalia. The UK sits in position 14.

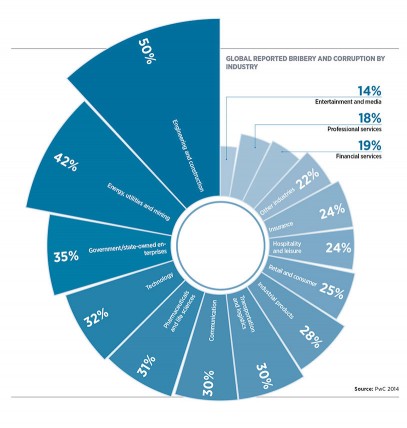

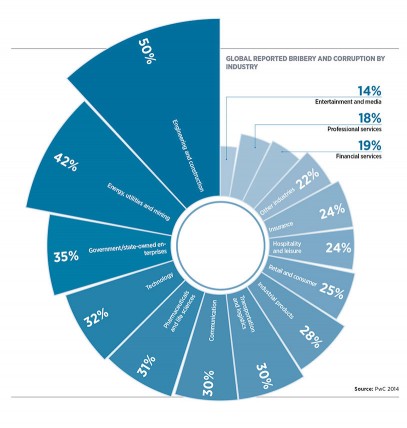

Industries regarded as posing the highest risks include energy, mining and defence. Mr McCluskey comments: “Extraction activities tend to take place in areas where the rule of law is non-existent and natural resource has always been ripe for bribery.”

The due diligence, says Mr Hyde, includes assessing the level of corruption in a country, the risk associated with the particular sector, the proposed third party, the level of government involvement, and a myriad of checks to investigate the reputation and reliability of the third party and the transaction contemplated.”

This, says Ms de Kluyver, can range from basic verification and ownership checks to very detailed reports on business and people’s reputations which, adds Mr McCluskey, may have spawned a “secondary industry of validation of partners and local vendors”.

Companies doing business in the United States need to be alert to the provisions of the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which many view as far more demanding

“Some jurisdictions and sectors may be viewed as posing too great a risk; there are still regions, developed and undeveloped, where grease payments and bribes are deep rooted in both commerce and culture,” says Mr Hyde.

In such circumstances, the ultimate protection, says Mr Hitchen, is to make the tough decision to not do the deal.

Under investigation

Since the UK Bribery Act came into force, there have been no prosecutions brought by the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) against companies. The prosecutor states there are a number of ongoing investigations, including into UK pharmaceutical giant GSK, Rolls-Royce, French energy and transport conglomerate Alstom, and oil and gas company SOMA, although it cannot disclose what they are about.

Aside from the Bribery Act, companies doing business in the United States need to be alert to the provisions of the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which many view as far more demanding. In addition, there is a trend in many countries to take enforcement action locally, either for political or revenue reasons, or through a genuine desire to stamp out corruption.

The SFO’s investigation into GSK followed its fine of $490 million (£297 million), having been found guilty in China of bribing doctors and hospitals to use its products.

So the anti-corruption climate is hotting up. As Mr Cole at Hogan Lovells concludes: “Major companies doing business around the world must be alive to the fact that they have to look over their shoulder in a number of different directions – a number of anti-bribery laws may apply even though the activity is not taking place in that country.”

Analysis: Bribery Act to date

Introduced by the Coalition Government in 2011, the Bribery Act 2010 was the biggest reform of UK anti-corruption law, sweeping away a myriad of disparate and ancient offences, and setting a global gold standard.

The then Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke heralded it as an “important step forward for both the UK and UK plc”.

He said: “At stake is the principle of free and fair competition, which stands diminished by each bribe offered or accepted.

“Tackling this scourge is a priority for anyone who cares about the future of business, the developing world or international trade.”

The act introduced four key offences: offering or giving a bribe; accepting a bribe; bribing a public official; and failing to prevent a bride.

Susannah Cogman, partner at global law firm Herbert Smith Freehills, recalls that when it first came into force, attention focused on fears the legislation might spell the demise of corporate hospitality.

Since then the focus has shifted to the number of prosecutions, or rather the lack of them. The Crown Prosecution brought the first prosecution in 2011, somewhat ironically against a magistrates’ court clerk who pleaded guilty to taking a £500 bribe for making a speeding charge disappear. Two other cases followed concerning bribes by a man who had failed his driving test and a postgraduate student who had failed a dissertation. Hardly the stuff to send shock waves through UK plc.

And although the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) has secured prosecutions against two tricksters involved in a £23-million scam to dupe investors into putting their money in a biofuel scheme, there have been no corporate prosecutions and no deferred prosecution agreements (DPAs).

However, the SFO confirms there are Bribery Act investigations underway, although it is unable to give “fixed numbers”.

The SFO has further indicated that the first invitation letters have been issued in relation to DPAs and it anticipates two will take place before the end of the year.

Lawyers believe there are many reasons why enforcement activity has been slow. Ms Cogman points out that the act has only been in force for four years and does not apply retrospectively. In addition, it takes time for offences to come to light and investigations are lengthy.

William Christopher, partner at London law firm Kingsley Napley, compares the UK legislation with the US Foreign and Corrupt Practices Act. “It came into force in 1977, but it took five years before the first prosecution and didn’t get going until the 1990s,” she says.

While the record of enforcement may have been far from impressive, it would be a mistake to judge the act solely on that basis. It has resulted in a sea change in the attitude of corporates to anti-bribery compliance, spawning a mini industry in compliance, and putting the issue high on the agenda of boards of directors.

Lawyers are inclined to give the enforcement agencies more time to show their teeth. It remains a credible story for the SFO to say it has a bank of investigations, but warns Jo Rickards, a partner colleague of Mr Christopher at Kingsley Napley: “You can’t keep saying, ‘we’re working on it’.”

UK Bribery Act

Compliance