POWER OF ACTUARIES

Actuaries may have long been the butt of jokes, but they also have traditionally taken many of the top jobs in insurance companies. However, actuaries, whose day job it is to analyse statistics, including morbidity and longevity, and use them to model risk and calculate insurance premiums, have lately been losing their grip on power. Michael Moss, author of a history of Standard Life, says their comparative decline reflects the changing nature of the products being sold – fewer “with profits” life policies, more mutual funds and unit-linked pensions. Insurance consultant Ned Cazalet says by designing shoddy products, such as mortgage endowments, through their “cluelessness about financial markets”, actuaries were authors of their own decline. “They hid behind Grecian pillars and presented themselves as sober, super-smart and conservative. But they were more like the Marx Brothers,” says Mr Cazalet. A 2015 paper for the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries said only 18 per cent of life companies’ executive directors were actuaries, down from 38 per cent in 1990. The report said: “It can be a concern that actuaries are increasingly being siloed as quantitative analysts.”

BANCASSURANCE

BANCASSURANCE

Back in 1999-2000, it was the Holy Grail of “bancassurance” that drove Lloyds TSB’s £7-billion acquisition of Scottish Widows. Already popular in countries such as France and Belgian, bancassurance involves banks and insurance companies coming under the same ownership to cross-sell each other’s products. However, the Lloyds-Scottish Widows deal has already partially unravelled when the insurance company’s asset management arm, SWIP, was sold off to Aberdeen Asset Management. Also tougher regulation is making bancassurance less attractive. HoewHow

“Banking and insurance are two different dynamics,” Jan Hommen, outgoing chairman of Dutch bancassurer ING, said a few years ago. “Banks are much quicker. Insurance is much slower. Insurance runs on a fifty-year life cycle. Banking runs on a five-year life cycle. The pace is different. The people are different. So why would you put them together? You’re just setting up a managerial conflict.” Financial historian Michael Moss adds: “In a bancassurance model, the pressure is to make margins, often by flogging things that should never have been sold. It has not been a success. In fact, it’s been a disaster.”

COMMISSION-BASED SELLING

It once predominated in the insurance sector, but commission-based selling led to mis-selling on a vast scale as it encouraged insurance firms to design products to maximise commission payouts to independent financial advisers (IFAs), irrespective of whether they ripped off customers. “Too many products were designed with the enrichment of salesmen as their raison d’être” says insurance consultant Ned Cazalet. The Financial Services Authority effectively outlawed the practice in December 2012, when under its retail distribution review, intermediaries like IFAs were forced to start charging their clients fees instead and to make these fully transparent. Many IFAs, reluctant to change their ways, annoyed by the newly introduced obligation to pass exams despite decades of experience, gave up the ghost, while many surviving IFAs decided they were now unable to serve anyone with investible assets of £50,000 or less. This has led to what many people in the industry call an “advice gap”. According to financial historian Michael Moss: “Many IFAs, as they existed before the review, were not that independent and didn’t really offer advice; they were often effectively tied agents, paid by commission which they never told the customer about. That was a bad tradition which has now largely been done away with.”

MUTUALITY

Mutuality, whereby a company is owned by its customers rather than by shareholders, was for a long time the favoured ownership structure in the insurance industry. It’s an ownership approach that can work to policyholders’ advantage. Since a mutual does not need to pay dividends to shareholders, it should have a larger pot of cash to share among policyholders and it theoretically also give customers a greater say in how it is run. Many insurers, including Standard Life, converted to mutuals between the 1920s and the 1960s, partly to make themselves immune from takeover. However, the pendulum swung back towards stock-market listings between the 1990s and early-2000s. That was because many insurers found themselves strapped for capital and saw conversion to plc status or selling out to banks as their only way of raising funds. “It was a great tradition and led to a quite different culture, as mutual insurance firms were answerable to individual policyholders, not corporate shareholders. Once they demutualised that was lost and they became driven by targets,” says financial historian Michael Moss. But research by Professor Robert Carter of Nottingham University found mutuals’ products do not necessarily outperform those of listed firms.

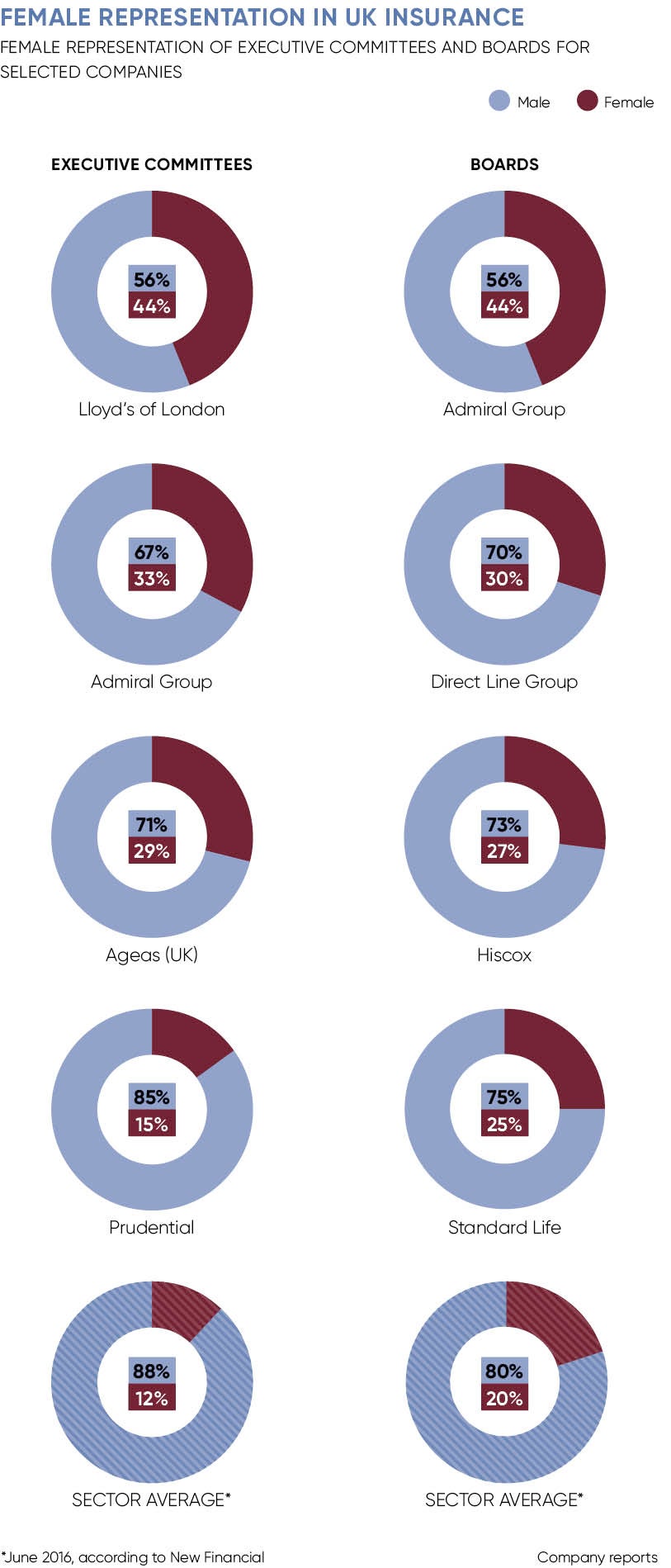

SEXISM

Insurance has long been a male-dominated industry, especially in middle management and executive roles. It was only in the 1960s that women started getting promoted to underwriting roles and, even then, they were paid less and offered fewer perks than their male colleagues. After conducting a survey of the industry, Eve Hartridge, then head of insurance and actuarial at Executives Online, concluded: “The insurance industry still has a long way to go in becoming a desired sector for women to work in.” Her research, published in February 2017, found that a “drinking culture” was limiting gender diversity within organisations, as was a lack of scope for flexible working which was putting women off. This echoed an earlier report from business services giant PwC in suggesting insurance firms were struggling to achieve inclusive and diverse workforces. At the largest insurance group Aviva, 52 per cent of staff overall, but only three of eleven board directors (27 per cent) are women. Even so, that represents massive progress on a few years ago and came after insurance market Lloyd’s of London broke the mould when it appointed its first female chief executive Inga Beale in December 2013. Richard Baddon, insurance partner at Deloitte, says faced with new challenges from fintech players, the insurance industry must look beyond the “conservative, innovation-averse talent” it has traditionally attracted.