Ten years ago, Rushd Averroës moved from Yemen to the UK to study. Keen to start settling into the country straightaway, one of his first steps was to try to set up a bank account. But, as he soon found out, getting access to finance wasn’t as easy as he had hoped.

“It was very hard,” says Mr Averroës. “Almost every traditional bank I went to didn’t let me open an account because they said I couldn’t prove my identity. Even though there were many ways to prove who I was, the banks only wanted to use the system they had been working with for years. This is where immigrants can feel excluded because a bank account is a basic human right.”

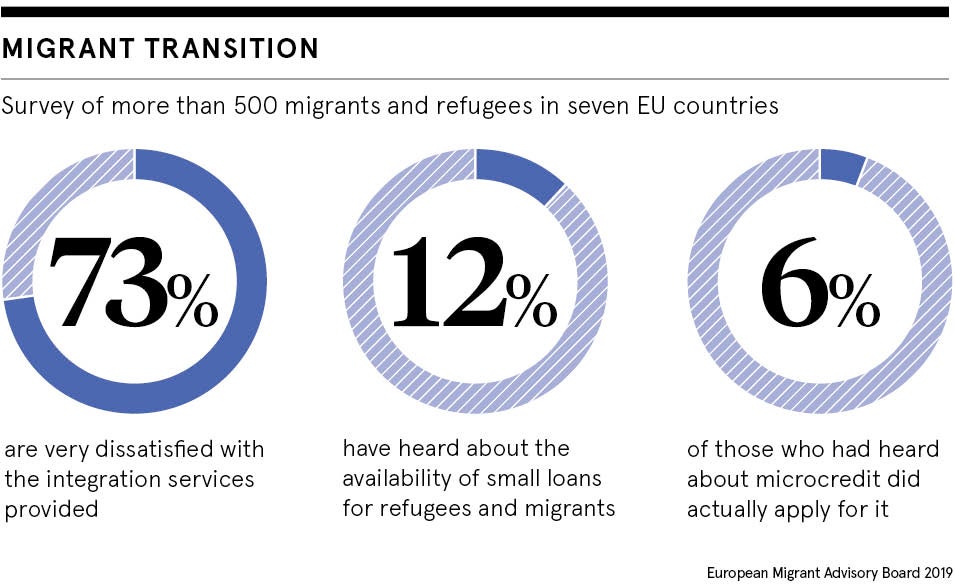

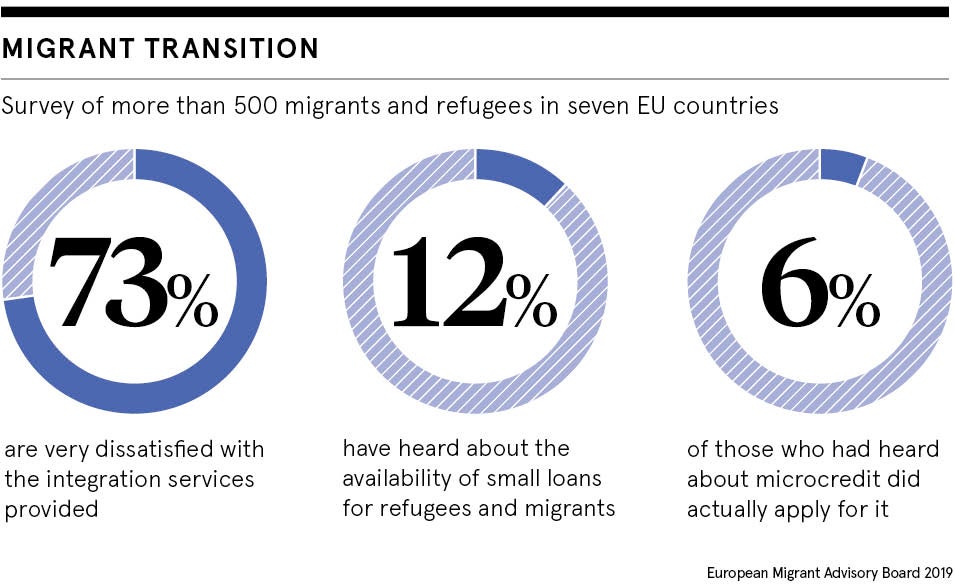

His difficulty in accessing traditional banking services is a common one among the world’s nearly 30 million refugees and asylum seekers. Their financial inclusion is being restricted by banking rules that prevent access to finance, not only opening a current account, but also getting a business loan. This therefore impacts how quickly new arrivals can start growing financial roots.

People can be unbanked but still financially savvy

Swati Mehta Dhawan, researcher and consultant on the financial inclusion of low-income households, has studied access to finance for refugees and asylum seekers in Germany, where immigration has significantly increased over the last few years, amid the arrival of nearly one million people, notably from Syria and Afghanistan.

“As people get into the system and integrate, they will end up performing a lot of financial firsts, like getting a rental contract, opening a bank account or registering a business,” she says. “They are bound to make mistakes because they don’t understand the system or the new language very well. While support for integration in the labour market was in place, we found that when it came to financial aspects, the support was not there.”

Almost every traditional bank I went to didn’t let me open an account because they said I couldn’t prove my identity

This gap within the context of immigration can, however, be filled by fintech solutions. In the past few years, companies such as Leaf, a virtual bank that allows refugees to save and transport assets securely across borders, and Now Money, a digital bank for migrants in the United Arab Emirates that helps them send remittances cheaply and easily, are playing a role in banking the unbanked.

US-based Accion Venture Lab, the seed-stage investment initiative of global non-profit organisation Accion, is supporting Leaf and has just launched a $23-million fund for inclusive fintech companies.

Vikas Raj, managing director of Accion Venture Lab, says: “From our perspective, the opportunity is twofold. There is more opportunity for fintechs working with migrants and refugees by using the same tools that others are already leveraging. Leaf, for example, is using a whole set of tools that didn’t exist ten years ago, including mobile money and blockchain. That would not have been possible before because not everybody had a mobile phone and blockchain was just an idea. We have these tools now.”

Discrimination driving limited access to finance

The issue is mainly down to discrimination and misunderstanding. Ms Dhawan says: “It’s important not to see refugees and immigrants as one homogenous group. These newcomers might have had limited interaction with formal banking systems, but in many cases they are successful entrepreneurs, skilled savers, have built assets and have extensive social networks for borrowing and lending through difficult periods.

“The problem is a lot of it was outside the formal financial systems and these skills cannot be transferred to countries that are highly formalised. This is where fintech can play an important role and move beyond traditional banking systems. It can help people build credit histories and, crucially, help in areas like remittance and lending.”

Fintech offers unique opportunity for financial inclusion

After his experience, Mr Averroës has founded his own company to address access to finance for the unbanked. Using blockchain and biometric identity, BABB aims to decentralise banking and provide peer-to-peer banking services to the global micro-economy. Through the BABB app, which launches officially in the next couple of months, users can open a UK bank account, send and exchange money.

He says: “We are designing for the micro-economy, so our system is much cheaper, and we require very basic identification at the beginning. The system is very inclusive; we are getting to the root of the issue.”

Despite some of the benefits fintech solutions can bring to immigrants and refugees, analysts say more needs to be done to ensure the full financial inclusion of such people in their new countries.

Scalable efficient solutions are still in their infancy, according to Mr Raj, who calls for both more innovation

and wider engagement with the problem.

“We need more startups innovating in this space, looking at models that work by leveraging technology, which didn’t necessarily exist before. Then you need investors like ours and our peers to support those companies. Finally, we need larger institutions, regulators, civic society, to integrate with these markets. That’s what

needs to happen. A whole heap of stakeholders needs to get hip to this.”

Similarly, Mr Averroës says local and central banks need to get involved. “The issue is not with immigrants and refugees only, or even the unbanked. What about the banked? In some cases, they are the families of the unbanked and need a platform to make a payment. We need one bank for the micro-economy that caters to everyone. I believe connectivity is everything. If we are not connected, it will be very hard to build a financially inclusive platform,” he concludes.

People can be unbanked but still financially savvy

Discrimination driving limited access to finance