The first modern-day Islamic bank was founded in 1963 in the dusty aluminium town of Mit Ghamr, 80 kilometres north of Cairo. The Mit Ghamr Savings Bank offered the usual loan and deposit facilities for local farmers and businessmen, but via a profit-and-loss-sharing model rather than charging or paying interest, forbidden under Sharia law. It also specialised in micro-finance and community projects, until it folded four years later.

Since that inauspicious start, Islamic banking has grown to become an important part of the global banking industry, forecast to reach $3 trillion by 2020. It’s growth mostly driven by demand from Muslim populations in Asia and the Middle East for financial products that not only don’t use interest, or riba, but have other Sharia-compliant characteristics. These include physical assets underscoring transactions, and avoiding investment in sectors such as alcohol and pork.

Now this growth is also being fuelled by demand from Africa’s 250 million Muslims in the continent where Islamic banking first put down roots 55 years ago.

Now this growth is also being fuelled by demand from Africa’s 250 million Muslims in the continent where Islamic banking first put down roots 55 years ago.

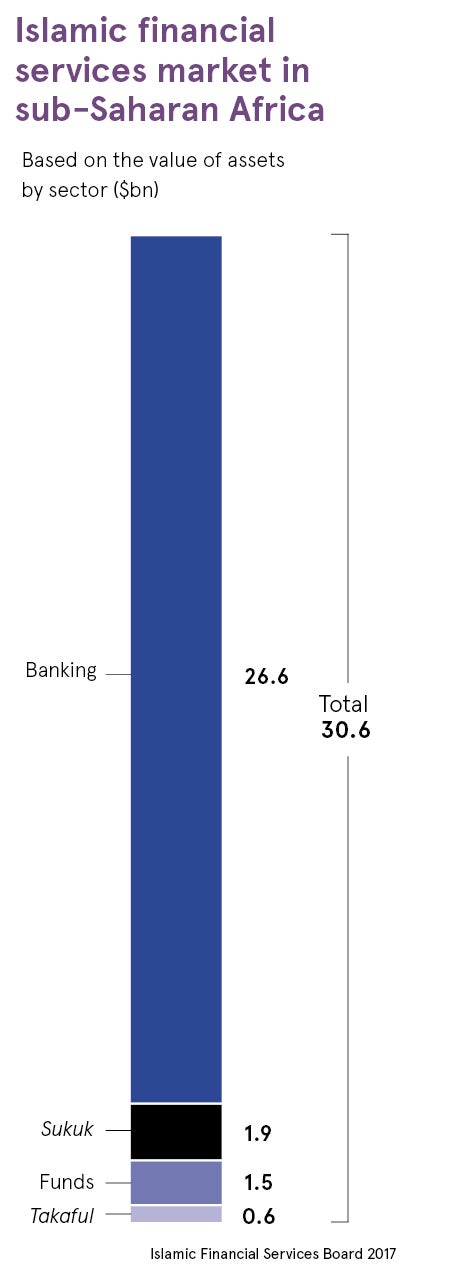

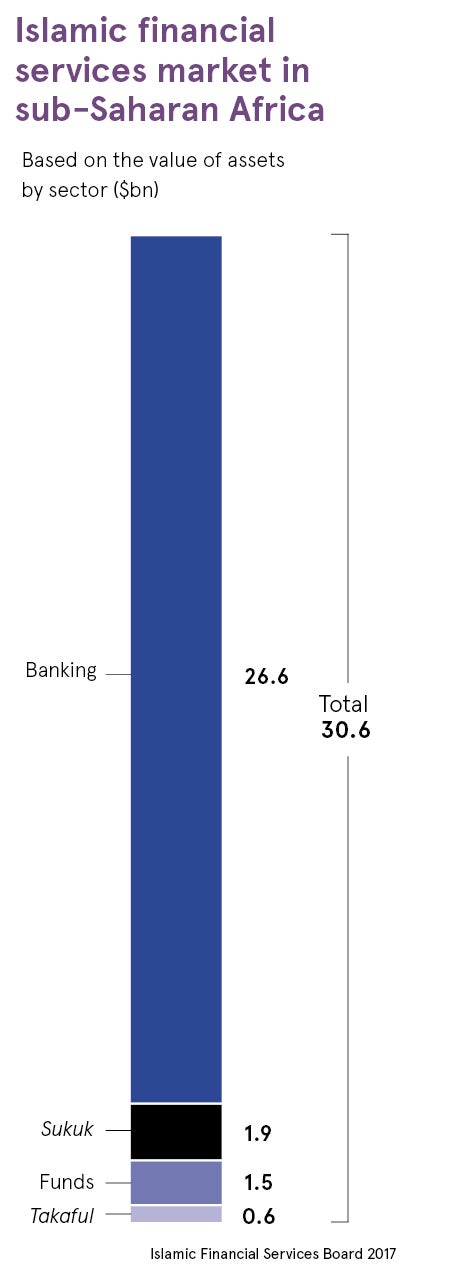

Regulatory body, the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), valued sub-Saharan Africa’s Islamic financial services industry at $30 billion in 2017. Much of that growth has come from African governments issuing sovereign sukuk, or Islamic “bonds”, to finance costly infrastructure. Countries from South Africa to Nigeria and Togo have issued sukuk, which have been snapped up by Middle East and Asian investors with a glut of savings looking for Sharia investments. In 2016 African governments issued $1.3 billion in Islamic bonds.

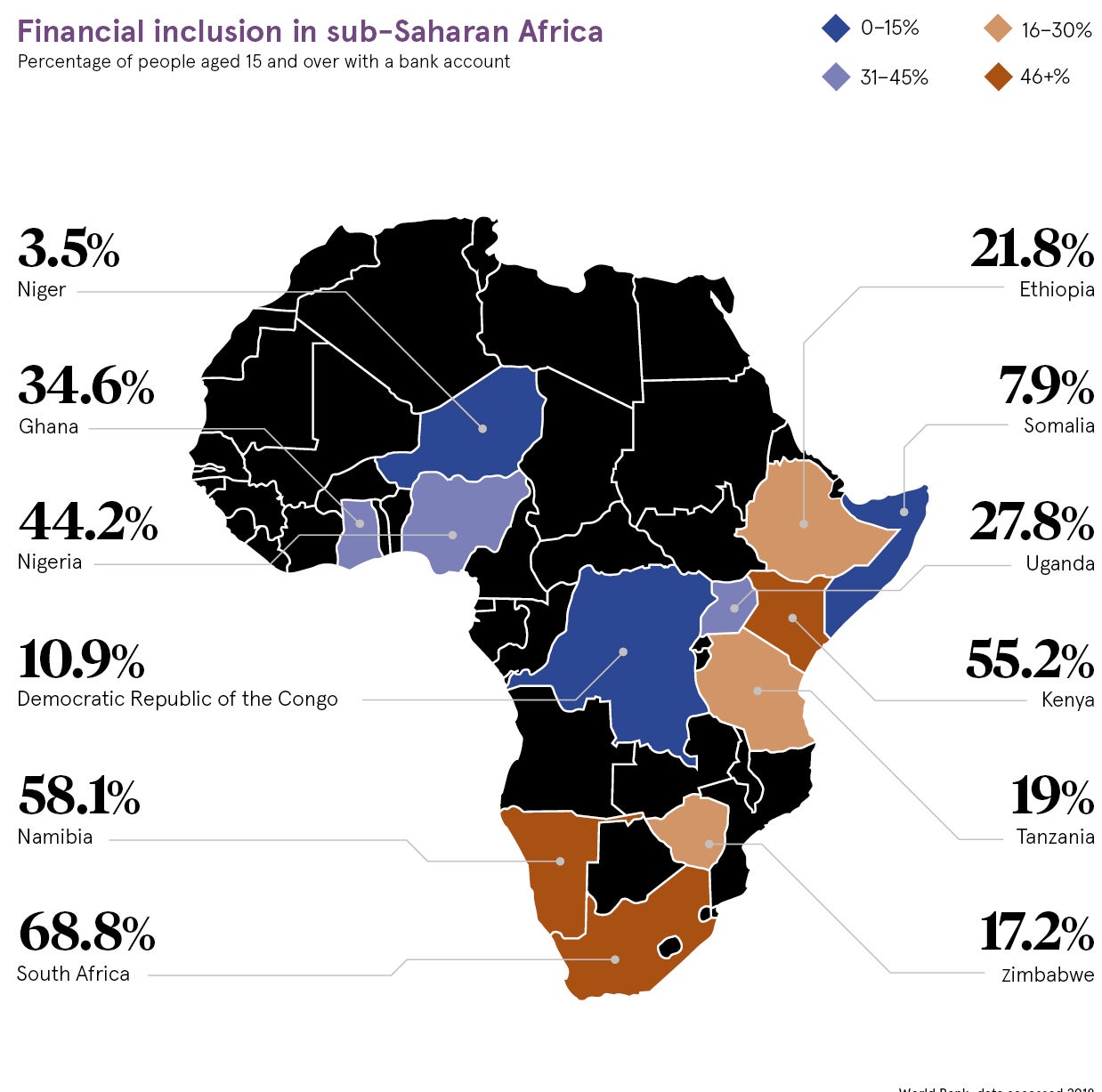

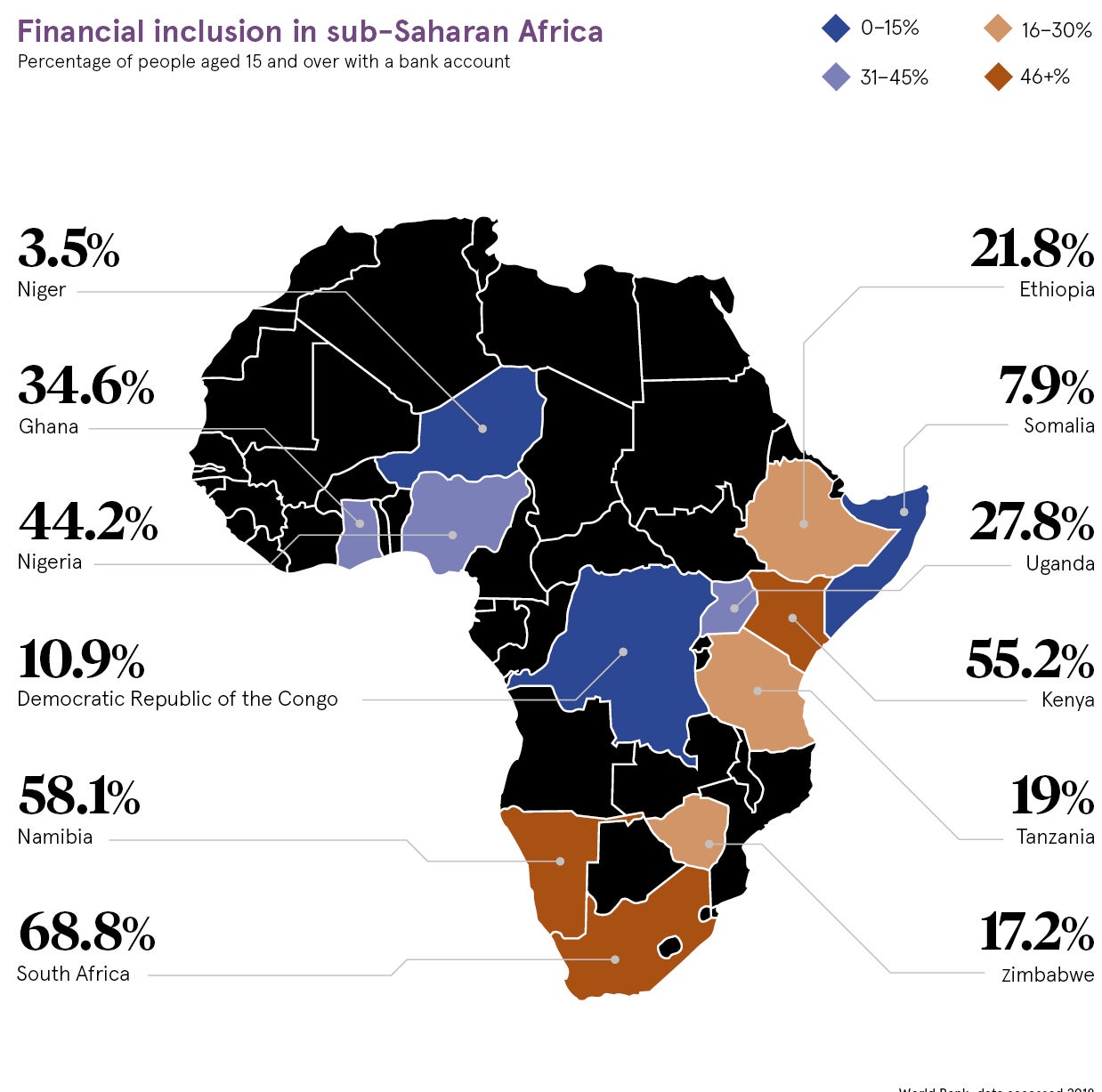

As the sukuk sector has taken off, so a continent-wide industry serving businesses and retail clients with Sharia-compliant products is beginning to be established. One hope is that Islamic finance could help extend financial services to Africa’s unbanked. The World Bank estimates as many as 350 million people don’t have a bank account in Africa, with countries home to large Muslim populations having the highest level of unbanked.

Banking champions, such as the National Bank of Egypt, FinBank of Nigeria, Absa Bank of South Africa and the First Community Bank of Kenya, have set up dedicated Islamic “windows” through which to offer Sharia-compliant products. South Africa’s wealthy can now invest with Sharia-compliant asset managers and Nigeria Jaiz Bank, Nigeria’s only dedicated Islamic bank, illustrates the potential of the market with healthy growth in profits.

Kenya, where 15 per cent of the 50-million-strong population are Muslim, has one of the most developed Islamic banking sectors in Africa, boasting three Islamic banks, licensed takaful or insurance businesses and a recently obtained membership of the IFSB. “The region’s huge Muslim community represents low-hanging fruit for Islamic banks,” says Onyango Obiero at Dubai Islamic Bank in Nairobi.

Mr Obiero, who heads up small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) banking, says Sharia’s joint-ownership model particularly suits financing Kenya’s fast-growing SME sector where underlying, concrete assets support loans and financing. “We finance machinery and trucks, and have become a player in the transport and construction sectors. We also provide trade finance, lending against stock and helping traders with their working capital,” he says.

But Islamic banks face the same challenges operating in Africa as traditional lenders. Sharia-compliant or not, banking requires things like collateral, property titles and documentation that many people don’t have, says Mr Obiero.

For bank customers with only a few, small transactions, the fixed costs make it too expensive. Many people live far away from their nearest bank and still prefer to borrow from family and friends, and keep their money under the mattress, rather than use formal financial institutions. It’s one explanation for the fact that countries such as Senegal and Niger, where most of the population is Muslim, have only one Islamic bank each.

A lot of money looking for a home from the Middle East is behind the growth of the sector in Africa

Moreover, much of the sector’s growth to date has been supply driven from Middle Eastern and Asian investors, rather than home-grown demand from African consumers. As investors from the Middle East have sunk money into sovereign sukuk, so it is banks from the Middle East that have put most of the capacity-building resources into the sector, says Thorsten Beck from London’s Cass Business School. “You have to bear in mind that a lot of money looking for a home from the Middle East is behind the growth of the sector in Africa,” he says.

Growth could also be limited in countries such as Kenya and South Africa, where Muslim populations are smaller. Yet Mr Obiero believes the Sharia banking model gives it a transparency and fairness that rivals conventional banking and will extend its appeal beyond an Islamic identity. “It can be for Hindus, Christians and unbelievers – the most important thing is the product,” he says.

Political instability is another potential problem. Many countries have been cautious about actively pushing the sector in case it stokes existing religious tensions. Nigeria, fighting Islamic terror group Boko Haram in the north, only has one Islamic bank and two with Islamic “windows”. It’s a banking sector still dominated by traditional lenders despite Nigeria’s 80-million Muslim population.

But Professor Mehmet Asutay from Durham University Business School believes the swathe of sovereign sukuk issues is indicative of increasing government support for the sector. “A sovereign sukuk provides legitimacy from the state,” he says.

Slowly but surely governments are building the regulatory framework the sector needs. Kenya recently introduced important changes to its stamp duty and VAT regulation to create a more level playing field between Sharia and conventional products. Explosive growth at Nigeria’s Jaiz Bank is linked to the government giving it a licence in 2016 to operate in all Nigeria’s 36 states. Elsewhere Uganda’s Central Bank is preparing Islamic banking regulation.

Innovation could provide a key to the sectors growth too. An example is Kenya’s mobile operator Safaricom and Islamic bank Gulf African Bank’s plan to launch M-Sharia, a Sharia- compliant banking service through M-Pesa, Safaricom’s mobile money service.

Success in Africa’s small, emerging economies could also include offering more of the services that Egypt’s Mit Ghamr Savings Bank pioneered back in the 1960s, according to Professor Asutay. Micro Islamic finance products and community finance, which clearly connect to Africa’s real economies and the volatile and vulnerable finances of ordinary people, would trigger more growth. “Africa needs capacity-building and financial empowerment on the ground,” he concludes.