Imagine a Sunday morning sometime in the future. As you pour milk on to your cornflakes, it’s a reminder that you intended to check out whether the Chinese company Big Dairy Inc is worth a punt. You press a button on your wrist monitor, ResearchBit, and it sends a request to your peer-to-peer investment network for any information on the company. Within minutes investor friends from around the globe are commenting via a private social media network, InvestBook.

As you munch through breakfast, you decide to do a bit more digging. Since voice recognition makes it so easy to logon to your wealth manager’s chatbot on your phone, you idly ask what a £10,000 investment in Big Dairy Inc would do to your portfolio.

“You’re already overweight in the Far East compared with your investment parameters. If you’re interested in Big Dairy Inc, you might also be interested in the US group Milk Bottlers Ltd,” it says. “I’ll drop a research note into your inbox. And why not play our online game, Fastest Milkman, in which you try to deliver enough bottles of milk to double your money?”

As you reach the marmalade stage, you’ve realised just how many bottles of milk it takes to turn a profit in milk – and you still can’t work out how to get past the tricky bit on level three of Fastest Milkman where the price of packaging keeps rising until you crash out into bankruptcy. Meanwhile, the chatbot reminds you of recent speculation that the US is about to join the EU, which could play havoc with your tax position, and points out that £10,000 invested now in your pension would mean you had met your retirement saving goal for the year.

By the time you pour your third cup of coffee, there are golden streamers popping across your screen and Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary playing from the speakers. “Woo-hoo! An instant transfer has gone through to your pension and you’ve met your biggest wealth target of the year,” says the chatbot. “That qualifies you for a 0.5 per cent reduction in fees on your next portfolio review. I’ve put a date in your diary to discuss updating your goals and suggested we work through the scenarios if you start a family. And have you thought about replacing that coffee with a green tea?”

Pure fantasy?

Well, maybe, but there again, no one disputes that the future of wealth management is increasingly automated.

The rise of automation

“Customer needs are changing,” says Sarah Newman, director at PwC. “Wealth management is behind the times and needs to step up to the online world. But the digital revolution isn’t about no human contact – it’s about getting the balance right.”

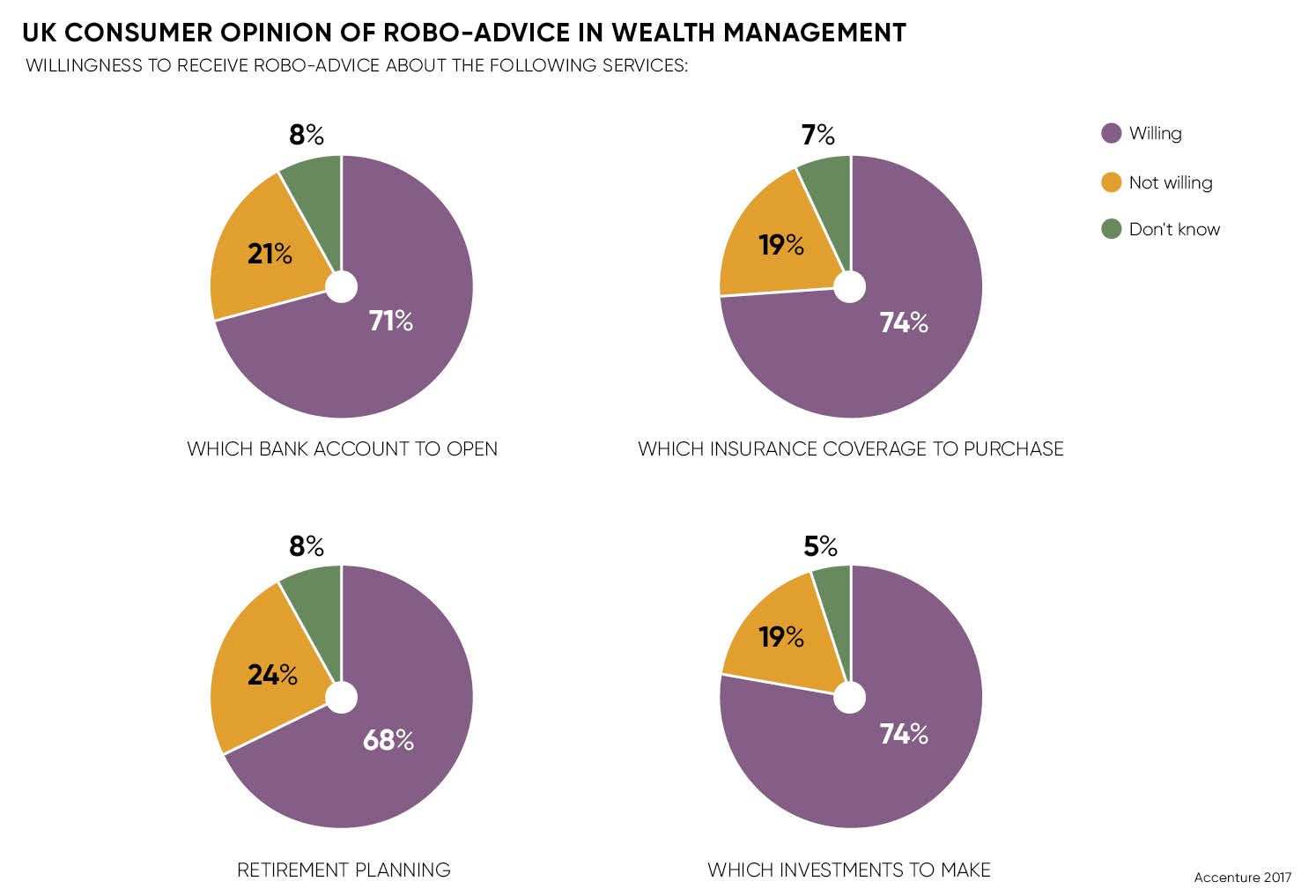

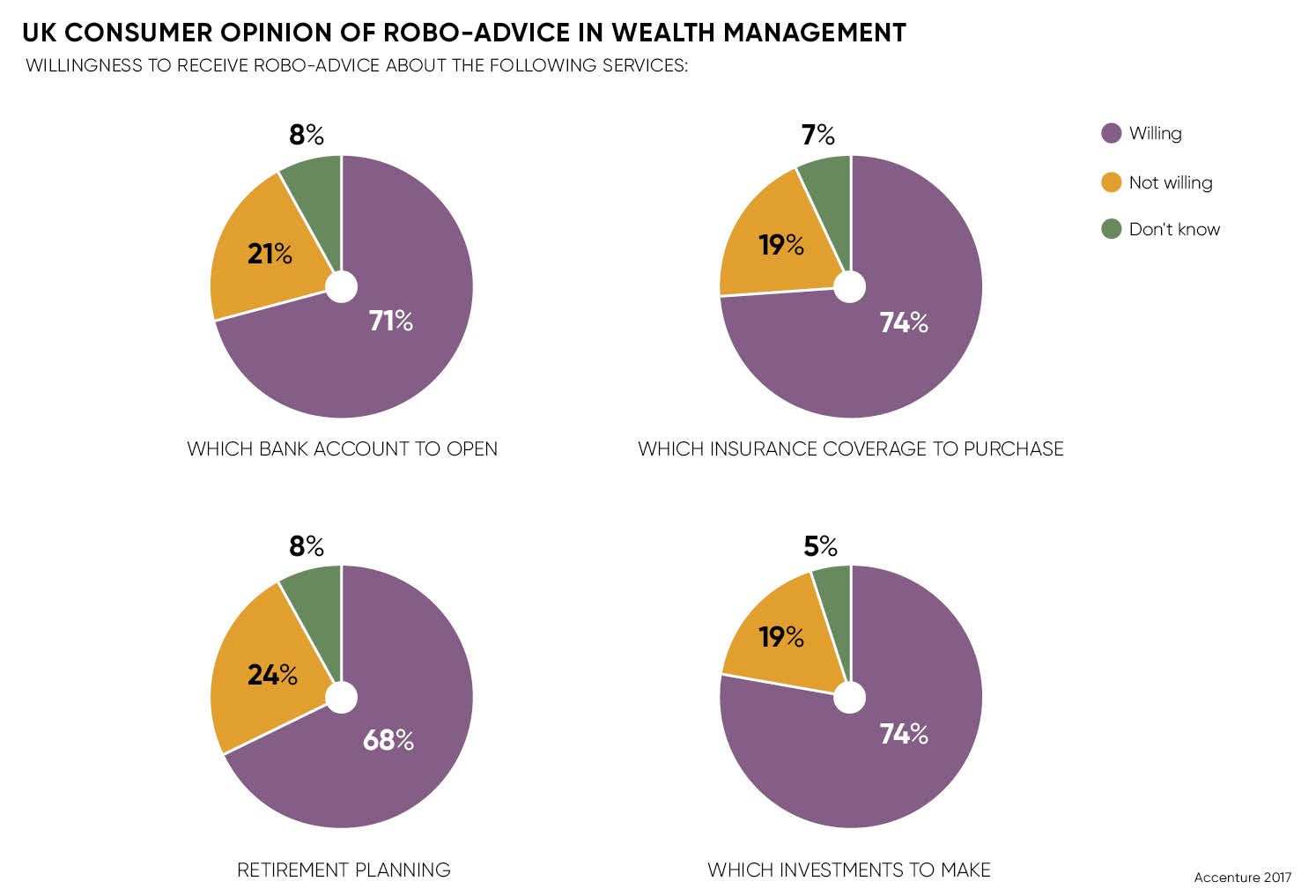

Robo-advice currently has its limitations. “It’s still very simple,” says Peter Kirk, managing director at Accenture. “But people trust robo-advice services – they feel in control.”

That could be hugely important in an industry that has struggled to maintain trust following various financial scandals. An Accenture survey in January found that a quarter of UK consumers saw the impartiality of robo-advice as a key attraction, while 40 per cent turned to it for convenience and speed.

Wealth managers already know the importance of being a presence on social media, but big data analytics will give them far more insight into your habits and preferences

“Millennials are much less loyal and wealth managers are going to have to work much harder to attract and keep clients,” says Jeremy Boot, product manager of wealth digital channels at Temenos. “Younger people would rather visit their dentist than their bank manager. But technology could be used to engage customers more – instead of a list of boring questions to determine your risk profile, why not an online game?”

Gamification, already used in the insurance industry, could be one way to improve the dull reputation of wealth management, which often struggles to persuade us that asset allocation is more interesting than a night out necking vodka shots. A reward-based game that translates thinking about money to life events such as buying a house could help change that.

Many would prefer to manage much of our money ourselves, according to Andrew Stewart, a partner at A.T. Kearney, and improving digital advice will allow us to do just that. But he adds: “There are still some very complex events or needs in life, such as a pension where people want face-to-face advice. Regulation has made that much more expensive, but technology is allowing us to create innovative and simple ways to articulate complex advice.”

Knowing your client

Technology is also going to create a picture of individuals that goes way beyond the “know your client” regulation that has caused financial services so many problems. Wealth managers already know the importance of being a presence on social media, but big data analytics will give them far more insight into your habits and preferences.

“Analytics can go much further in understanding the client,” says Mr Boot. “Once you have artificial intelligence and machine-learning, you will be able to add a much more targeted service.”

In one sense this is simply a better version of today’s actuarial work; already, our financial choices are affected by the broad-brush strokes of gender or age or whether we smoke. But technology will be able to crunch through so much more data that the adviser of the future could know us better than we do ourselves.

And that could flip us back to the machines, according to Ms Newman. “People may not want to talk about every life choice with a human,” she says. “We are already seeing technology that allows you to take your present situation, plug in different life events and get it to feed out what is needed to make it happen or the probability of reaching a goal.”

Perhaps the biggest change will be the speed with which we can get the data we need to make decisions, says Mr Kirk. “The opportunities for technology to change the industry are limited by the products – a current account is still a current account,” he says. “It’s about improving and streamlining the journey, making real-time decisions. After all, machine-learning can be fooled and it still needs a human to program it.”