I meet a lot of senior executive teams of large banks. Some are visionary, many are committed and a large number understand that life is changing. Few understand how.

I talk to them about the fintech world of change and how millennials are reshaping banking, from Stripe, started by two brothers who were 19 and 21 years old, to Venmo started by two friends in their 20s, to Klarna created by some guys who were working at a big-brand burger chain in Sweden.

I talk to them about how distributed ledger technology (DLT), also known as blockchain, is reinventing the back office of banks along with artificial intelligence and machine-learning, and their eyes sometimes glaze over.

I talk to them about how new thinking about money is coming out of the cryptocurrency world and particularly how Africa is seeing changes by using mobile phones and DLT to move massive volumes of small transactions for no charge. They look a little non-plussed.

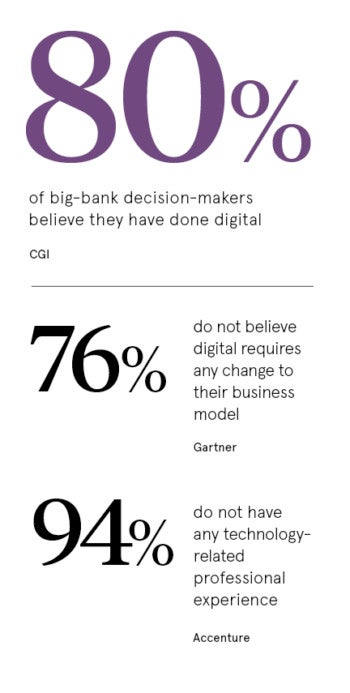

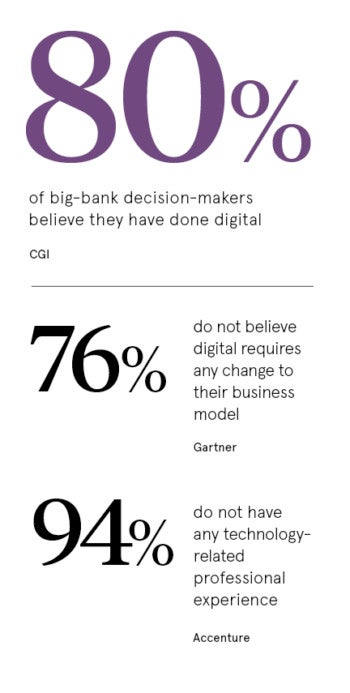

I related these things to you because I’m a great collector of statistics and I know for a fact that the majority of big-bank decision-makers have no idea what digital is. For example, a recent survey by CGI, an IT service provider, found that 80 per cent of the big-bank decision-makers believe they have done digital. Another survey by Gartner Group, an IT market research firm, found that 76 per cent of the decision-makers at most large banks do not believe digital requires any change to their business model.

Digital is a complete transformation of the fabric and foundations of the organisation

These results are quite stunning when it is obvious that digital is a massive, fundamental shift of their business model. A bank’s business model was developed in the industrial revolution to enable cross-border commerce with trust. This is why banks are regulated and licensed by governments, which gives them that trust, and why most banks are the oldest institutions in their respective countries.

The model is based around a focus on the physical distribution of paper in the localised network focused on buildings and people. Banks controlled the whole value chain of that network, and designed and built everything themselves.

Then along came technology in the 1950s and the giant computer firm IBM, which sold big back-office boxes to banks through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. The idea was simple: get rid of the paper transaction systems in the branch, and automate the ledger of debits and credits in a head-office system. This way the head office could track and trace their whole branch network of ledgers immediately. It cut costs, increased security and made the banks far more efficient.

Then along came technology in the 1950s and the giant computer firm IBM, which sold big back-office boxes to banks through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. The idea was simple: get rid of the paper transaction systems in the branch, and automate the ledger of debits and credits in a head-office system. This way the head office could track and trace their whole branch network of ledgers immediately. It cut costs, increased security and made the banks far more efficient.

When other technologies came along, they were added on to this big central system. Call centres, ATMs and internet banking all followed, and all show a record of your debits and credits. Then mobile banking made an entrance at the same time as cloud computing, big data, cryptocurrencies and open sourcing, and it has ripped that whole system to pieces.

This is why a 21-year-old university dropout could start a bank called Loot. It is why two friends could spin out of one challenger bank, Starling, and start another called Monzo. It is why a Chinese company, Ant Financial, in partnership with India’s Paytm, has become the biggest financial firm in India, in less than five years.

There are many other examples, but the key to all these is that they do not do everything themselves. They use APIs (application programming interfaces) to find partnerships with other providers that can do the work for them. Loot is backed by Wirecard. Starling Bank has 25 partnerships through APIs to offer full service banking from pensions and savings to insurance and mortgages. Ant Financial offer a marketplace of APIs to companies worldwide and are used by some of the biggest banks in the world to do the things they cannot do, such as processing payments using QR codes.

These developments are called various things from platforms to marketplaces, but I like to call it open banking. I don’t mean “open banking” in the regulatory sense, but in the sense of a business model. A bank that historically controlled everything is now open to everything.

This business model is a reimagination of the old physical one as it is built from the ground up using today’s technologies to focus on delivering a customer experience that is exceptional, and through their tech devices rather than through a physical interaction. In other words, the industrial-era business model of banks based upon branches is replaced with the digital-era model of banks based upon servers. This is a completely different business model and focuses on the digital distribution of data through software and servers on a global network of systems called the internet.

So why would a senior decision-maker in a bank believe they have done digital, and it requires no change to their business model, when it is clearly obvious to those who know technology that digital is a massive cultural, business and organisational transformation based upon a wholly new business model?

Well, the key words in that sentence are “to those who know technology”, because most senior decision-makers do not know technology. Banks are run by bankers, not by technologists, except the new digital banks need also to be technologists, otherwise they are just a bank, not a digital bank.

Can I prove this? I think so. A recent analysis of big banks’ annual reports found that 94 per cent of their leadership have never had any professional experience of any role in their career that relates to technology. That’s a serious flaw and is the reason why most big banks think they’ve done digital because yes, they’ve rolled out a mobile app. Guys, that’s not digital. Digital is a complete transformation of the fabric and foundations of the organisation and, until you realise this, you are letting your organisation rot.

Chris Skinner is chairman of the Financial Services Club