In the world of policymaking, few issues are as contentious as pension reform. There are a couple of reasons for this.

On one hand, the optics are terrible: bureaucrats in suits telling hardworking individuals they need to do more with less; grandparents potentially struggling in their golden years, unable to enjoy the fruits of their labour; young people realising the benefits available to the current generation of retirees simply won’t be there for them.

On the other hand, the general public has only a vague understanding of how pensions work, much less how, sometimes, the system needs to be tweaked. Voters want better roads, hospitals, schools, more jobs: tangible things that can make a difference in the short term. Overhauling an entire country’s pension system is akin to start turning a cruise liner miles before the iceberg even comes into view. Most of us can’t, or refuse to, think that far ahead.

Is the Brazilian pension system too generous?

But one of the world’s largest economies has decided to take on the challenge. The Brazilian pension system is, by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development standards, absurdly indulgent. It allows workers to retire in their mid-50s; it lets widows and widowers receive their spouses’ full benefits; Brazil spends seven times as much on its oldest citizens as it does on programmes for the youngest, such as education; the average for Latin America is four times.

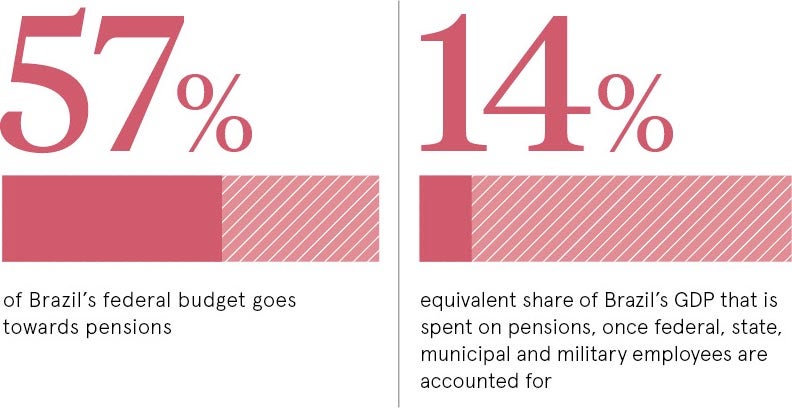

Even more alarming is the impact the Brazilian pension system has on the country’s public finances. It is estimated that pensions gobble up 57 per cent of the annual federal budget. Once federal, state, municipal and military employees are accounted for, pensions swallow the equivalent of 14 per cent of GDP.

This kind of expenditure is similar to that of countries like France, Italy and Greece, except in those countries the population is much older. For a relatively young nation, with so many needs in so many areas, the amount of funding allocated to pensions is financially unsustainable.

In the words of Mariano Bosch, senior economist and pensions co-ordinator at the Labor Markets and Social Security Unit of the Inter-American Development Bank, in Washington, this pension reform went from “being an option, to becoming unavoidable”.

“What the government is trying to do is to put a break on pensions expenditure,” says Vilma Pinto, economist and researcher at the Brazilian Economics Institute of the Getúlio Vargas Foundation. “The state’s modus operandi so far has been to keep on raising taxes to generate more revenue. But to ask people to pay higher taxes is now unacceptable. Brazilian society will not stand for that anymore.”

Barriers to pension reform in Brazil

In many ways, the proposals of Jair Bolsonaro’s maligned right-wing government have long been the norm in most developed countries. In an effort to save 1 trillion reais (£212 billion) over the next ten years, Mr Bolsonaro wants to raise the retirement age to 65 for men and 62 for women, increase workers’ pension contributions and reduce some workers’ pension benefits. In a country fresh off the most severe economic recession in its history, those changes are seen as crucial to kick-start the economy.

For the better part of this century, implementing those measures has been virtually impossible. The 13 years of Workers’ Party rule will forever be remembered as the era of socially progressive policies, which helped mitigate the country’s chronic inequalities. Curbing the benefits of elderly people was never going to be done under its watch. Today, those on the left of the political spectrum remain suspicious of the Bolsonaro-led reforms, even if on paper they are set to hit the wealthiest the hardest.

“The pension levels are not going to change for those on the lower income bracket,” says Dr Bosch. “The people who are retiring in their 50s, those are not the low-income people. So if you ask me who is going to be most affected by the reforms, I would say it’s the people who were retiring early, with high pensions.”

Is raising retirement age realistic?

When it comes to the Brazilian pension reform, a quantitative analysis to crunch the numbers concludes that if the government doesn’t change tack it will go broke. But graphs and spreadsheets seldom tell the whole story. Looking at the problem through a qualitative lens is crucial. Context matters. Retiring at the age of 65 in Brazil is not the same as retiring at 65 in the UK or France.

“Take a worker on a sugarcane plantation deep in the countryside,” explains Dr Ruy Braga, sociologist at the University of São Paulo. “If I tell you that a worker chops down 8,000 sugar canes per day and harvests for 20 straight days, and then if I tell you that at 35 that worker won’t be able to lift his arm because his back has been so badly damaged, how do you expect that person to work until the age of 65 so he can retire with a government pension?”

Change is coming for Brazilian pension system

And yet, lawmakers might just get their way. In the last two decades, a number of attempts have been made to fix the Brazilian pension system. Earlier this year, the country’s infamously fractious lower house of the National Congress passed the latest version of a reform bill by a large margin of 370 votes to 124, comfortably above the threshold of 308 votes it needed.

The base text of the bill will now undergo a review in the lower house, then a senatorial commission and two votes before full sessions of the Senate for final approval. A final approval of the legislation is expected in September, although it could stretch into October.

The business community is waiting for the passage of the bill to start investing again. But even if the bill becomes law, Brazil’s economic woes will be far from solved.

“This will have to be revisited in five or ten years,” says Dr Bosch. “This is not the reform that will put the Brazilian pension system on a sustainable path. This is the beginning of a series of changes that will have to be made in the next two decades to fix the system.”

Is the Brazilian pension system too generous?