Blockchain has been the “next big thing” for payments for some time. The concept of a dependable and trusted source of data about customers, transactions, ownership of assets and other kinds of payment information is not lost on bankers.

Also secure, blockchains are not held on any single server, but distributed across a global network of computers. Every time the information is amended by a user with a cryptographic code, the copies of the blockchain on all systems are updated. This decentralised approach makes them effectively unhackable and immutable.

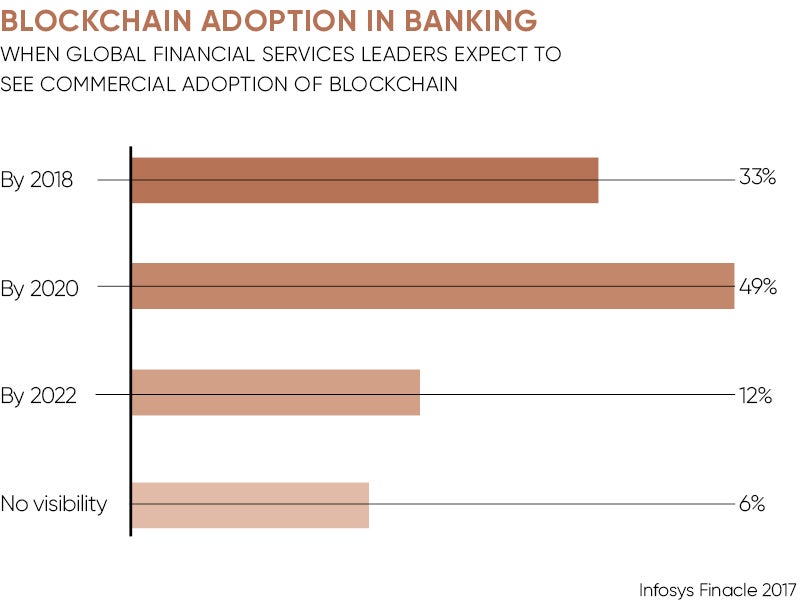

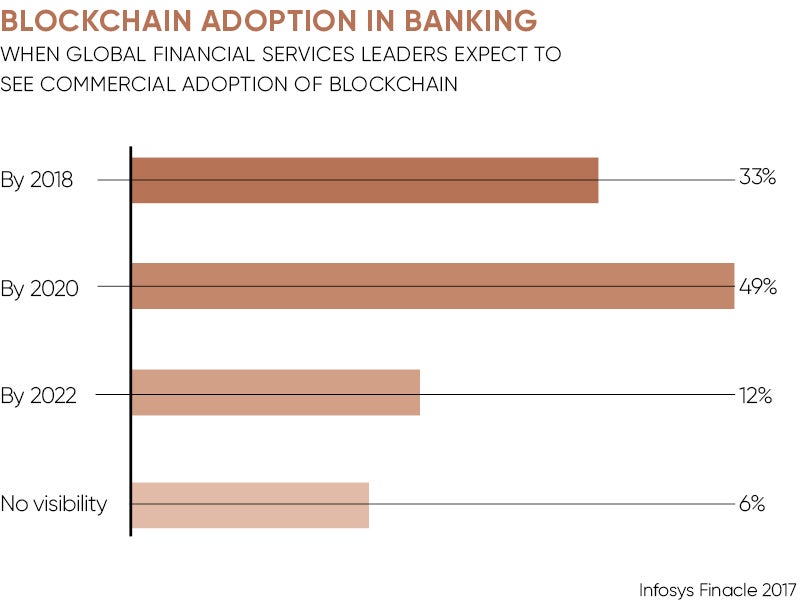

A recent survey of bankers by Infosys Finacle found that more than 80 per cent expect to see commercial adoption of blockchain by 2020, with about half already investing or planning to invest during 2017. Half of the banks surveyed are even working directly with fintech companies on the technology.

There are clearly many potential uses of blockchain technology, including combating identity fraud and money laundering, improving know-your-customer systems, and speeding up cross-border payments, letters-of-credit processes and the granting of loans. But the financial sector is not yet ready to commit fully to this new era. For blockchain technology to be effective, it requires sharing data, while the banks’ business models depend on storing and utilising it.

There are lots of incumbents, legacies and particular interests that are going to prevent the adoption of the new technology

“Banks still see the data they hold about an individual as a source of competitive advantage. They are not yet able to sit around a table and share that insight and intelligence with other banks as they think they will lose that advantage,” says Tony Craddock, chief executive of the Emerging Payments Association, whose organisation represents payment providers across the world. “There are lots of incumbents, legacies and particular interests that are going to prevent the adoption of the new technology.”

However, banks are investing in disruptive fintechs because they know technology has upended other sectors before and could do the same to them. “That’s the risk. If you’re an incumbent, the risk of being disrupted by new players is very significant. That’s why banks are investing significantly in blockchain because they don’t want to be left out,” Mr Craddock explains.

Blockchain startups are coming to the fore, often with the support of major banks and investors. Circle, which enables users to make payments via text message, has received $136 million of investment from a consortium of backers, including Goldman Sachs, IDG Capital Partners, Breyer Capital and Accel Partners. It has also partnered with Barclays Bank in the UK as it doesn’t have a licence to hold consumers’ money. But the vision of its chief executive Jeremy Allaire is revolutionary and highly disruptive – it wants to make all payments free.

“We can share content and make calls for free with Facebook, Skype and Google, and we believe, because of blockchain technology and AI [artificial intelligence], we can provide that kind of experience for payments. We don’t think there’s going to be a model for charging for payments in the future – that’s just gone,” he says.

Some blockchain startups want to create new kinds of transactions. TrustMe, led by chief executive Antony Abell, is pioneering a new form of property investment based on blockchain. Through a new marketplace, due to launch this year, people will be able to buy and sell shares in London property for as little as £250. “London property is prohibitively expensive. It needs to be democratised,” says Mr Abell.

The business is targeting homeowners in need of equity release. However, Mr Abell says his new model could also make it easier for young people to get on the property ladder. “Up to 49 per cent of the property could theoretically be paid for by someone else, without you having to pay any interest on it,” he says. “The younger generation could, theoretically, move into a property owning 51 per cent, with the balance being paid for by investors who just want it for its stored wealth. That could change everything.”

The efficiency savings blockchain offers to payments reconciliation mean it is too tempting for the banks to ignore

Jon Matonis, vice president of corporate strategy at blockchain research company nChain, was also a founder of the Bitcoin Foundation. He was an early backer of blockchain and cryptocurrencies, and his enthusiasm is undimmed. The efficiency savings blockchain offers to payments reconciliation mean it is too tempting for the banks to ignore, he says.

“Prevailing wisdom states that there is a potential $20 billion in cost-savings to be realised by banks via improved blockchain reconciliation processes. That is not a revolution in finance – it is a revolution in reconciliation,” Mr Matonis says.

But the reputation of the financial sector is still recovering following the 2008 crash. Could a more visible and comprehensible banking system, based on new technology such as blockchain, prevent another crisis? Mr Matonis says the stability of the financial sector could be improved, but technology alone won’t prevent a crash.

“Blockchain can drive more accurate accountability, with near real-time clearing and settlement, so potential problems are not hidden from market participants and allowed to induce catastrophic misallocation,” he says.

However, Mr Matonis says the banking sector needs to commit to using blockchain technologies for the majority of their clearing work before the safety benefits can be truly realised. “We are a long way from that state of affairs,” he says.