The main players in global capital markets – investment banks, asset managers and stock exchanges – collectively generate some $500 billion in revenues each year. But according to William Wright, founder of think tank New Financial, this is far from sufficient to ensure their survival.

The industry is in the middle of a “perfect storm”, he says, in which revenues and margins are being driven down by tighter regulation, the rise of technology, changed social expectations and latterly also by Brexit.

Our clients in investment banking understand that, in the future, their industry will be a technology game with a banking licence attached

Some incumbent financial institutions, ill-prepared for the technological changes that are revolutionising their industry, are still deploying customer-unfriendly business models, processes and intermediated value chains that haven’t much changed for decades.

Asset management margins under threat from tech platforms

This is creating an opportunity for far-sighted insurgents, which are not burdened with legacy systems or tied to obsolete practices, to embrace new technologies and ways of working to disrupt the established players out of existence.

Though margins in asset management have held up at around 40 per cent in the 11 years since the financial crisis of 2008, Christian Edelmann, co-head of Europe, Middle East and Africa financial services at Oliver Wyman, warns they are at risk of plummeting.

“We see a scenario in which asset management will be transformed through the rise of an Amazon-style marketplace distribution model, in which price will be evermore important,” he says. “In this scenario, we believe 50 per cent of traditional asset management fees could be at risk.”

Mr Wright adds that other storm clouds looming for asset managers include regulators “now looking at the industry from consumer and competition perspectives, rather than from a purely financial stability or a conduct perspective”. He also believes job numbers will come down as artificial intelligence and technology replace human investors and traders, and not just at one or two quant-based hedge funds.

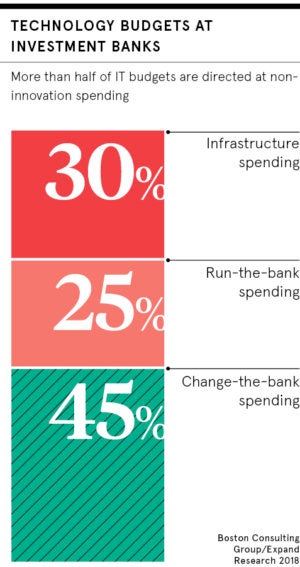

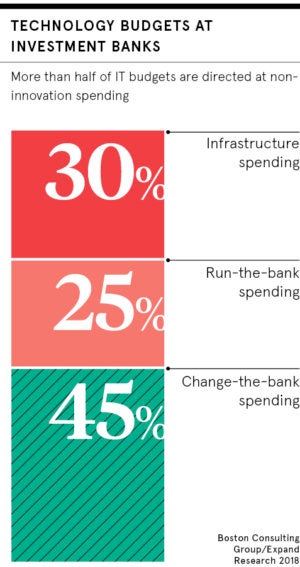

Some investment banks better equipped to change than others

Investment banking is facing similar pressures. European banks, unlike their Wall Street rivals, have seen profitability decimated since the 2008 crash, with some firms opting to withdraw from investment banking altogether.

Mr Edelmann says: “Our clients in investment banking understand that, in future, their industry will be a technology game with a banking licence attached.”

Better capitalised and more profitable Wall Street investment banks are better placed to make the transition to modular platforms than more troubled European players and are likely to be the long-term survivors.

According to Mr Wright, any player that lacks £200 million or so to invest in super-efficient new trading systems or super-efficient back-office processes is going to struggle or fail in the new environment. Others expect the investment banking business will fragment along the more specialised lines, as existed before Margaret Thatcher’s government liberalised financial markets with the so-called Big Bang in October 1986.

How blockchain and digital currencies are making their mark

It may have been founded in 1850, but SIX Swiss Stock Exchange is ahead of the game when embracing new technologies is concerned. The Zurich-based bourse’s head of securities and exchanges Thomas Zeeb has confirmed it will launch the SIX Digital Exchange. SDX promises to be a groundbreaking digital asset exchange, powered by blockchain, a distributed ledger technology which records data across a network of computers rather than on a centralised server. It will start trading digital tokens in a pilot phase from next month.

It may have been founded in 1850, but SIX Swiss Stock Exchange is ahead of the game when embracing new technologies is concerned. The Zurich-based bourse’s head of securities and exchanges Thomas Zeeb has confirmed it will launch the SIX Digital Exchange. SDX promises to be a groundbreaking digital asset exchange, powered by blockchain, a distributed ledger technology which records data across a network of computers rather than on a centralised server. It will start trading digital tokens in a pilot phase from next month.

Mr Zeeb says tokenisation will enable smaller companies that would normally be unable to launch initial public offerings (IPOs) and participate in equity markets or to issue bonds to do so, and that it will also broaden the pool of capital. “The cost of doing IPOs and issuing bonds will come down dramatically, opening up funding options for smaller firms and for project financing,” he says. “There will also be new asset classes; you can tokenise property and fine art.”

The London Stock Exchange (LSE) is also gearing up for the use of blockchain technology in the trading of financial instruments. In April it hosted the first issue of equities using blockchain-based tokens, when round £3 million-worth of shares in the fintech firm 20|30 were floated in tokenised form. The LSE has also invested in the London-based fintech startup Nivaura, which has issued the world’s first automated crypto-denominated bond.

Capital markets will be irrevocably changed by Brexit

Even though consolidation of ownership among European stock exchanges can be expected to continue, Mr Zeeb doubts whether there will ever be fewer than one exchange per country. “We’re seeing nationalism growing rather than decreasing in Europe,” he notes.

Mr Wright says European policymakers are going to have to do more to broaden and deepen the continent’s capital markets. European corporates currently obtain 75 per cent of their funding from banks and just 25 per cent from the bond markets, the exact inverse of what happens in the more developed US capital market.

“The clear view is that you need to reduce dependency on banks and that, by going more towards a capital markets structure, you will create more attractive and diversified opportunities for investors,” he says, adding that Brexit is going to “break the European capital market in two” undermining such plans.

Mr Wright singles out a surprising disconnect between the outlook for capital markets activity, which he says is generally very rosy as “the number of companies seeking to raise capital, the amount of sales and trading activity, the number of people becoming wealthier and putting money into savings and investments” is going up. For industry players, especially in investment banking, “profitability is being driven down, causing the hollowing out of what has traditionally been a highly profitable endeavour”, he says.

“I’m bullish on the outlook for activity, but bearish at the industry level. Within this, not everybody is going to suffer to the same extent. A small number of large firms are likely to become even bigger and more profitable. And a large number of smaller, less profitable firms today will either disappear or find themselves merging with other firms in a desperate attempt to make the economics stack up,” says Mr Wright.

SIX Swiss Stock Exchange’s Mr Zeeb predicts an even bigger revolution for the capital markets industry: “Over the next 15 years, I am convinced we’re going to see more changes in how capital markets function than we’ve seen in the last 40 years,” he concludes.

Asset management margins under threat from tech platforms

Some investment banks better equipped to change than others

How blockchain and digital currencies are making their mark