The UK has been a nation of enthusiastic debit and credit card users ever since their widespread introduction in the 1960s. The earliest charge cards debuted a decade earlier in the United States; they were made of cardboard and were designed to allow diners to settle their restaurant bills at the end of the month.

Today, of course, our plastic-hewn cards do more than merely settle restaurant tabs, with the card industry handling billions of transactions every year. According to the UK Cards Association, UK businesses accepted 15 billion card payments totalling £647 billion in 2016.

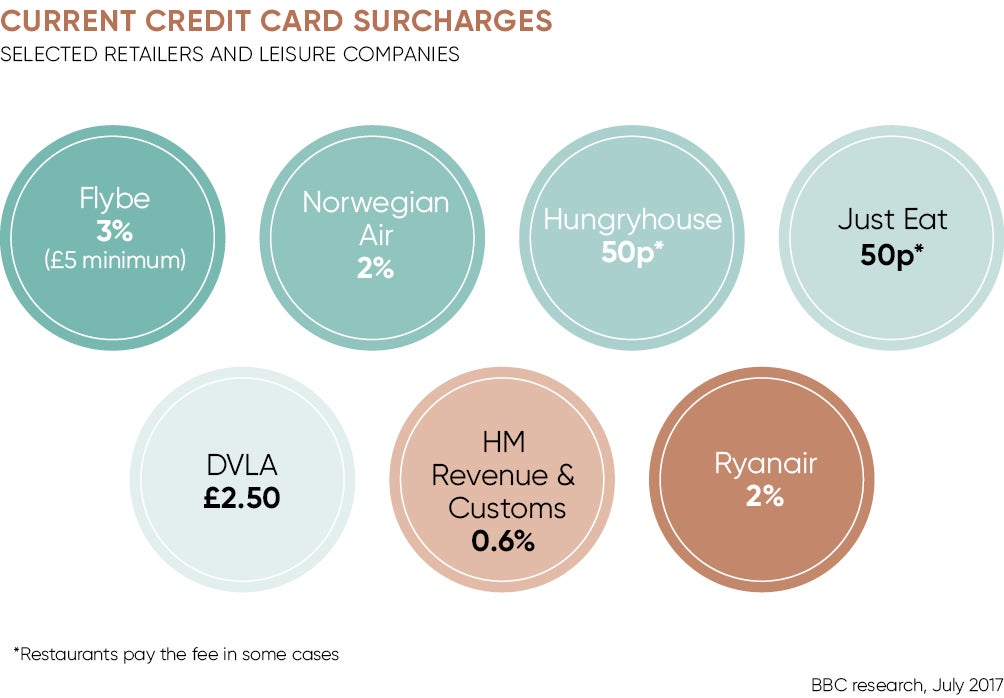

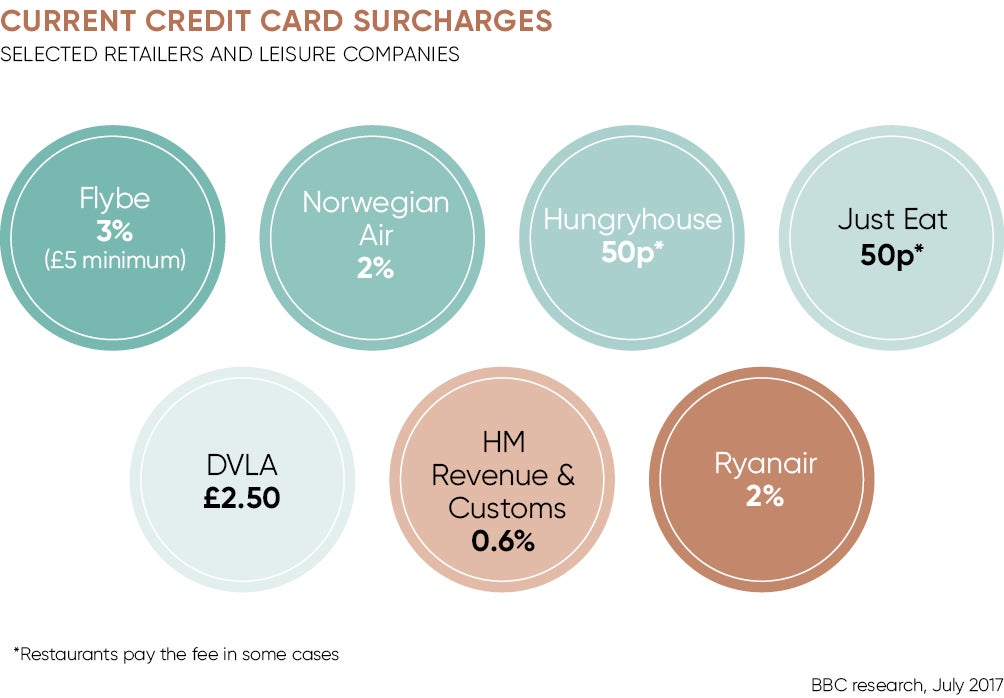

Despite such ubiquity, shoppers can still find themselves charged extra to pay by card. Well-known card fee culprits include airlines, ticketing websites and government agencies. Their surcharges are often confusingly rebranded as “administration” or “card-handling” costs and slapped on as a surprise at the final point of purchase rather than announced upfront.

Consumer rights campaigners Which? estimate the cost of processing a debit card transaction to be no more than 50p, but surcharges often bear little relation to this figure. The Treasury’s last estimate of the total value of surcharges incurred on UK debit and credit cards was around £473 million a year, leading to concerns that surcharges have been used by some merchants as an additional source of revenue.

At present, customers must simply accept the charge or not buy the product. When researching this piece, one purchase at a post office and another in a corner shop incurred extra card charges of 70p and 60p respectively, both representing well over 20 per cent of the total transaction cost. Neither person manning the tills could explain what the charges represented, but from January 13, 2018 this will all change.

Under new rules issued by the European Commission, retailers will be banned from using surcharges to pass the cost of card payment processing on to customers.

While most retailers already absorb the cost of card processing into the overall price of a product, others who use surcharges and operate on thin margins, such as airlines and travel agents, may find their bottom line affected. The series of events and players involved in making a single card payment goes some way to explaining why these retailers feel surcharges are necessary.

For the customer buying something with a card is usually a single action, a tap or a click, over in seconds. But what takes place behind the scenes to enable this involves a chain of companies in a process which has remained largely unchanged for decades.

Whenever a card is used, the retailer will typically use a company known as an “acquirer” to process the payment. The acquirer will pass the card details to the card scheme, such as Mastercard or Visa. The card scheme then passes this information on again to the issuer of the customer’s funds, which is usually a bank or financial institution. Once the issuer authorises the payment, the card scheme will pass the payment back to the acquirer, which in turn finally pays the merchant.

With all these moving parts come fees. Retailers have to pay the acquirers a merchant service charge for their work and in turn acquirers must pay an interchange fee set by the card schemes. Each part of the chain has its own margins to make and it is the costs involved in this process which have fuelled some retailers’ arguments that they should be allowed to apply surcharges to card payments.

Principal policy adviser at UK Finance Briony Krikorian-Slade likens this process to the costs of using road or rail infrastructure. “Essentially, retailers are contributing to the costs of running the system, which benefits all parties,” she says.

It is likely that retailers will look to pass on the cost of accepting payments in other ways

Retailers who use card surcharges will have to decide whether or not to adjust their prices in the incoming surcharge-free era. Law firm Hogan Lovells’ Emily Reid and James Black specialise in consumer finance. They say the surcharge ban “looks like good news for consumers, but it is likely that retailers will look to pass on the cost of accepting payments in other ways”. Ms Reid and Mr Black suggest this could play out in increases in the headline price of goods, higher unrelated charges, charging more for delivery for instance, or introducing new charges altogether.

However, the ban is part of a series of EU measures intended to make the cost of card payments cheaper and more transparent. Brussels has also placed a cap on interchange fees to reduce costs for acquirers, which in turn should reduce fees for retailers.

Exactly how the surcharge ban will be enforced is unclear. Retailers are already banned from making a profit from surcharges under UK consumer rights legislation enforced in 2012, but as the aforementioned trips to the newsagents and post office show, such rules can be hard to enforce. Mr Black says: “It is difficult to say with certainty, but the fact that those [2012] regulations have been followed up with the caps on interchange and now the ban on surcharging for most consumer transactions suggests they had little effect.”

Local trading standards authorities will be responsible for enforcing the ban, and Which? finance expert Gareth Shaw says these enforcers will need to keep a close eye on how the new rules play out online and shop floors next year. “It is crucial that the regulator closely monitors the charges that payment schemes impose on retailers, so that consumers don’t pay over the odds and this new law serves its purpose,” says Mr Shaw.

But retailers must accept that card fees or no card fees, as a nation, we now favour plastic over cash. According to the UK Cards Association, cards were used to pay for 76.4 per cent of all UK retail spending in 2016, a figure Ms Krikorian-Slade says is expected to rise in 2017. If retailers want to remain competitive in this landscape, they will need to find ways to absorb the cost of the UK’s surcharge-free future.