About two-and-a-half years ago, Goldman Sachs was said to be toying with the idea of launching a bitcoin trading desk, a move that would have spectacularly legitimised cryptocurrencies. Up until then, they had widely been regarded as the purview of speculators, nerds and criminals.

It was the beginning of bitcoin’s glory days. The price rose meteorically at the end of 2017 and hit a record high of just below $20,000 in December of that year. It was hailed a haven, even likened to gold.

But this year, as the coronavirus has sent global markets into an excruciating tailspin and investors scrambling for safety, comparisons between bitcoin and the yellow metal seem misguided: the volatility of cryptocurrency has rendered it too hot for many to handle.

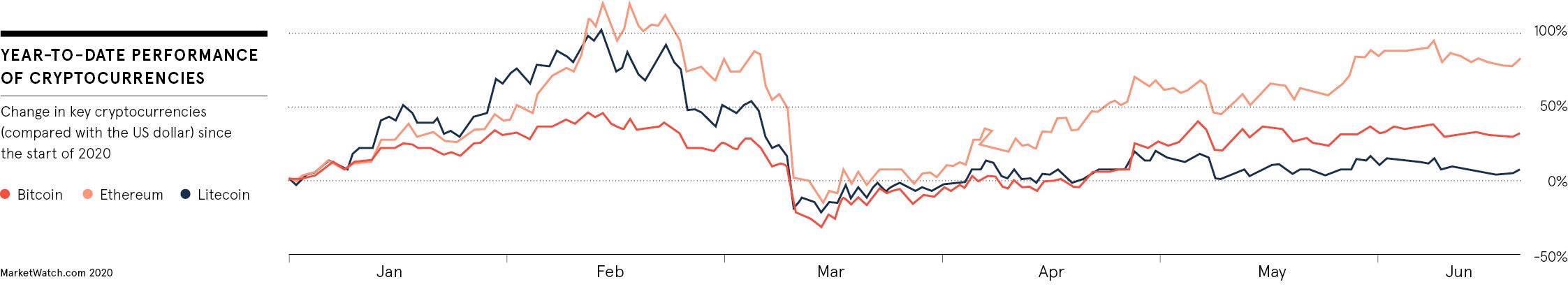

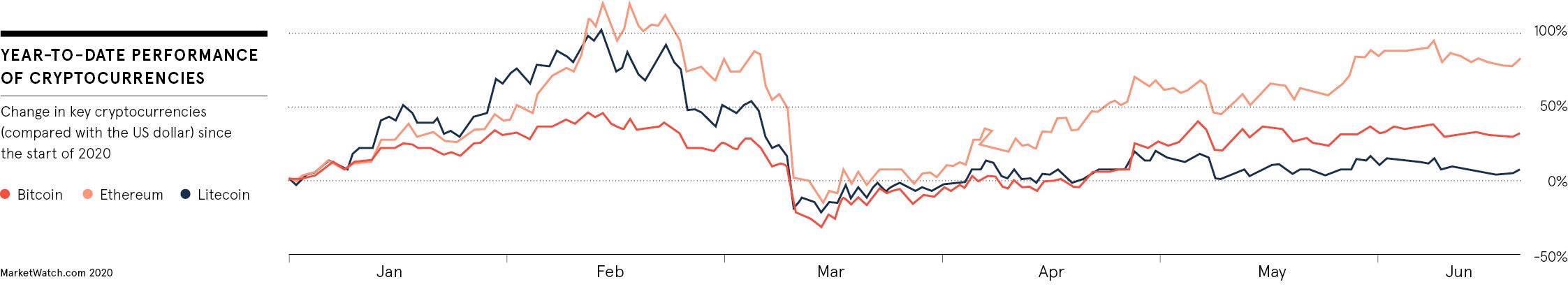

In mid-March, as global stocks endured their worst trading sessions in decades, bitcoin suffered a 26 per cent single-day fall in value, its largest in seven years, according to Reuters. It has recovered since and has actually outperformed gold for the year to the middle of June, but it’s trek higher over the last 12 months has resembled a frantic rollercoaster of surges and crashes, while gold has tracked a steady climb.

The volatility of cryptocurrency

In a presentation to clients at the end of May, Goldman Sachs, in a turn of sentiment from just a few years ago, explicitly recommended against investing in bitcoin, even though the volatility of cryptocurrency might lend itself to momentum-oriented traders.

“We believe that a security whose appreciation is primarily dependent on whether someone else is willing to pay a higher price for it is not a suitable investment for our clients,” the bankers noted, adding: “We also believe that while hedge funds may find trading cryptocurrencies appealing because of their high volatility, this allure does not constitute a viable investment rationale.”

Others have also expressed doubt over cryptocurrencies’ true worth as a viable investment asset, particularly during times of economic crisis and considering extreme price movements. Recent slumps have left some funds reeling. Adaptive Capital, a cryptocurrency hedge fund, reportedly shut its operations permanently in May, citing the risks associated with such an unstable environment outweighing any potential benefits.

Neil Wilson, chief market analyst at Markets.com, also explains that as a viable alternative to fiat currencies, defined as government-issued currencies that are not backed by a physical commodity, or gold, cryptos have their drawbacks.

“The problem with the armageddon hedge idea is that you need computers to work and be able to access the internet, so cryptocurrencies have not got that war hedge element you get with gold,” he says.

For something to be considered as money, it needs to have three characteristics: store of value, unit of account and medium of exchange. At the moment, Wilson says, cryptocurrencies like bitcoin “don’t really fit any of those very well”.

A study published by academics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands this April warned that a lack of legal clarity posed a risk to investors if crypto-custodians go bankrupt. “Clear and generally accepted rules to deal with legal risks arising from the insolvency of crypto-custodians are currently absent,” the authors concluded.

But for every skeptic and doubter, there seems to be an enthusiast and many contest that the decentralised nature of cryptocurrencies, coupled with limited supply, makes them a good hedge against at least some of the impact of geopolitical tensions and reverberations of monetary policy.

The digital currency long game

Julian Sawyer, European managing director at Gemini, a New York-regulated cryptocurrency exchange and digital asset custodian, says it’s important to focus on the value of crypto over the long term and also its array of potential uses.

“Blockchain technology and cryptocurrency are not just passing fads and both technologies promise to play major roles in our future,” he says. “COVID-19 has shaken the global economy, including the financial services industry and people are re-evaluating their personal finances and how they can shore themselves up against financial hardship in times of upheaval.”

Sawyer, who co-founded Starling Bank, says low interest rates and generally increased volatility in stock markets have driven more people to new asset classes, such as cryptocurrencies, and that this is a trend which is likely to continue. As demand grows, the industry will mature and expand, he says, helping to address problems for consumers around online privacy and security, for example.

Bitcoin and ethereum are currently the largest cryptocurrencies by market capitalisation, but others are emerging at a rapid pace. Basic attention token, or BAT, which the designers characterise as a “utility token” rather than a currency is intended to be exchanged between users, advertisers and publishers on a blockchain-based platform, as a means of understanding and tracking how people engage with online content. Orchid is a cryptocurrency that can be used to buy extra bandwidth for online security and ChainLink is a platform that aims to bridge the gap between smart, or self-executing, contracts that exist on blockchain and real-world applications.

“As these use-cases develop, there will be more long-term viability for cryptocurrencies beyond trading and speculation,” says Sawyer.

Mustansar Iqbal, founder and chief executive of Auto Coin Cars, a cryptocurrency automotive trading platform, also says that as an investment class, cryptocurrencies are becoming more resilient to broader market volatility than they used to be.

“The dip that occurred during this crisis was far shorter in comparison to the last dip of December 2018,” he says. At that time, bitcoin dropped to a market value of around $3,157 and took several months to recover. As of the middle of June, bitcoin was trading at around $9,773, having dropped to $4,904 in mid-March.

“Cryptocurrency assets remain a reliable choice for the public,” says Iqbal, “and can therefore be reasonably classed as a viable choice for the future too.”

The volatility of cryptocurrency