It’s one of the fastest growing markets in UK financial services, yet you still won’t find many equity release products on the high street.

Sales of the plans, which allow homeowners to access the equity tied up in their property, have increased almost unchecked over the past decade, driven by a combination of factors likely to continue propelling the UK equity release market for years to come.

The amount of equity unlocked using the products more than doubled to £1.1 billion between the second quarter of 2016 and the final quarter of 2018, Aviva figures show. Sales jumped by more than a fifth in 2018 from 2017, according to Key, an equity release broker, the seventh successive annual increase.

And while Key reported a slower pace of growth in the first half of 2019, citing economic conditions, most expect that to be a temporary blip. Later-life lending could hit £397 billion by 2024 and £548 billion by 2029, the Centre for Economics and Business Research has predicted, up from £200 billion in 2014.

The most common form of equity release is a lifetime mortgage, through which homeowners aged 55 and over can take out a loan secured against their home, with the loan and interest typically repaid with the proceeds of the eventual sale.

The other mainstream option is a home reversion plan, where part or all of the home is sold to a provider for below market value in exchange for either a regular income or a lump sum and the right to remain in the home indefinitely.

Equity release meeting a growing need

Demand for the plans has risen for a host of reasons, not least demographics and the changing shape of retirement. With the number of people aged 65 and over expected to increase by more than 40 per cent during the next two decades, according to the Office for National Statistics, millions face the challenge of funding a retirement that could span 20, 30 or even 40 years and which is increasingly likely to feature the need to fund long-term care.

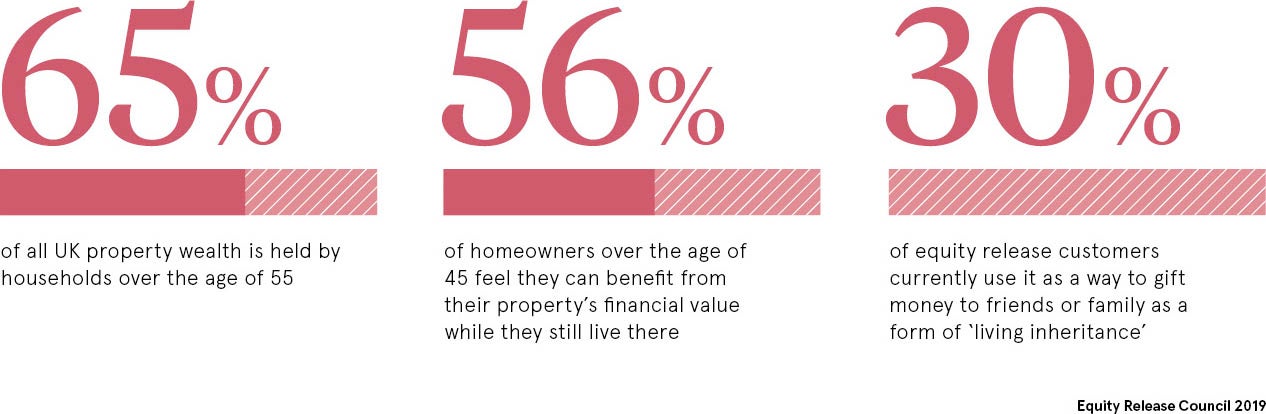

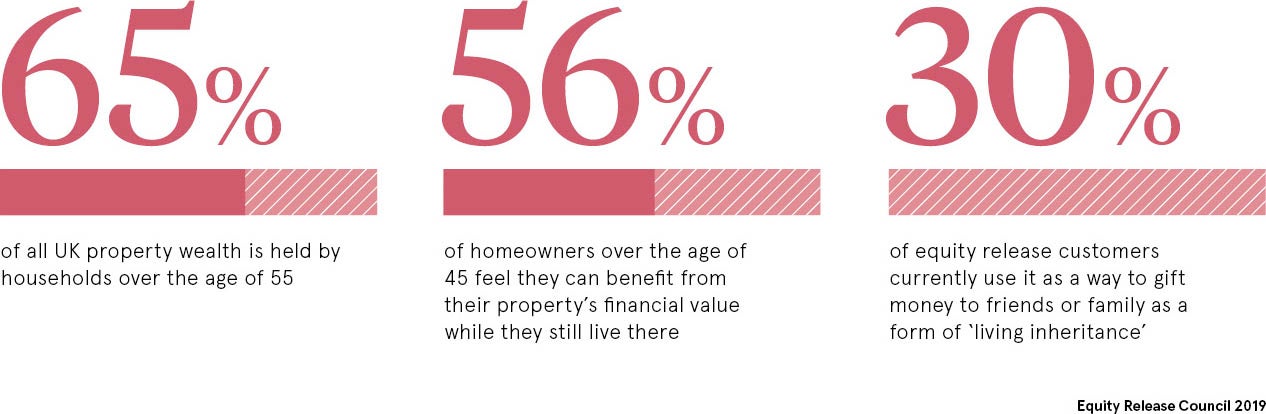

Prolonged house price growth means much of the wealth of older generations is concentrated in property.

“There has been an acceptance that, in the main, we are living longer and healthier, so people want to keep enjoying themselves and this ultimately costs money,” says Craig Palfrey, certified financial planner at Penguin, a Cardiff-based wealth management firm.

The effects of rising longevity on later-life finances are compounded by the demise of defined benefit pensions and the implications of the 2015 pension freedoms.

Will Hale, chief executive of Key, says: “While pension freedoms gave people more control over their money, they did mean that rather than using their savings to provide a guaranteed income for life, they could use them to meet more pressing needs such as repaying a mortgage.”

In other words, housing equity can fill the long-term gaps left where pension savings have been used to meet those short-term needs.

New lifetime mortgages focus on flexibility

Growing demand has encouraged providers to evolve product propositions. The market was previously dominated by lump sum options at interest rates around 7 to 9 per cent.

Now, the most popular type of lifetime mortgage is a drawdown arrangement allowing borrowers to take small amounts of equity at a time. Monthly interest servicing and inheritance protection are more widely available, while the average interest rate recently fell below 5 per cent for the first time, helping mitigate concerns about interest compounding.

While high street banks remain on the sidelines, Nationwide Building Society recently launched later-life lending options including lifetime mortgage and retirement interest-only (RIO) loans, as well as access to advice.

RIO loans, although similar to equity release, are regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority as mainstream residential mortgages. Advisers don’t need additional qualifications or permissions to advise on them, making them more attractive than products for which they do need to meet extra criteria.

A bumpy road

But there are challenges facing the market. One is a lingering mistrust, owing to a chequered past, with shared appreciation mortgages sold in the 1990s leaving a particularly unfortunate legacy and many borrowers with huge debts.

The industry has evolved since then and its reputation is improving, helped by greater regulation, tighter controls and an Equity Release Council code of conduct featuring a no-negative-equity guarantee.

We are living longer and healthier, so people want to keep enjoying themselves and this ultimately costs money

However, there remains a reluctance among many financial advisers to advise on equity release. Research by LV= found that seven in ten advisers felt uncomfortable discussing equity release with clients, citing complex products, a lack of knowledge and difficulties working out if the plans were suitable for the client.

Adviser misgivings reflect certain wider concerns over the risks of equity release, despite tighter regulations. For instance, interest compounding means the amount owed can mount up rapidly and often leave little or nothing to pass on to family.

Flexibility is now a growing feature of the market, however, and several providers are developing hybrid products that combine RIOs and lifetime mortgages.

The UK equity release market faces challenges, not least in making specialist advice more widely available and managing the effects of any housing market downturn. But with at least two high street banks developing later-life propositions, it seems certain to continue growing.

Equity release meeting a growing need