A new era in banking is upon us. In January, open banking was launched across the European Union, giving a new generation of service providers a chance to thrive.

At the heart of the movement is data-sharing. Open banking, under the EU Revised Payment Services Directive, or PSD2, means third parties can link up to a consumer’s high street bank account, so long as he or she consents. Mobile app Yolt is a great example. It gathers data from a consumer’s multiple accounts and provides an aggregated overview of their spending habits.

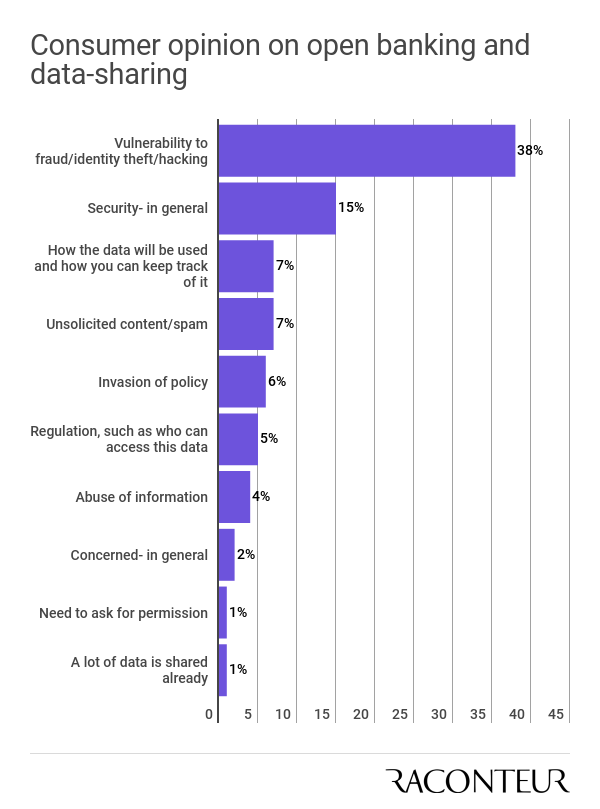

But open banking might also mean a new era of fraud. RBS chairman Howard Davies warns: “We are not confident that our customers’ data will be protected from hackers and thieves. We cannot refuse to hand over data because that’s what the legislation says, but we will have to try to educate people to understand the vulnerability.”

New threats of fraud in open banking

So what are the new threats? “Copycat websites could pretend to be third-party providers,” says Chris Moses, senior operations manager of Blackstone Consultancy, a private security agency. “Or a scammer could hack into a third party to gain access to information held in current account statements. Or pose as a third party in correspondence to extort information. This could then allow them to access customers’ money fraudulently. Information, such as who your utility contract is with, could be used to extract money as part of a more complex scam.”

And it might not always be hackers misusing data. Legitimate third-party providers may be the ones with a lackadaisical view on how consumer data can be used. Alex Bray, assistant vice president of consumer banking at Genpact, a technology and consulting company, sees an obvious potential abuse with open banking.

And it might not always be hackers misusing data. Legitimate third-party providers may be the ones with a lackadaisical view on how consumer data can be used. Alex Bray, assistant vice president of consumer banking at Genpact, a technology and consulting company, sees an obvious potential abuse with open banking.

He says: “Customer data could be used for purposes other than those agreed by the customer; for example, their data could be sold on to unscrupulous marketers or fraudsters for use in identity theft.” This can cause a ripple of future problems. “Fraudsters could phish for client details tricking customers into giving approval to access account information. This data could then be used to dupe customers into providing more sensitive data later.”

Mr Bray stresses that startups could be especially vulnerable. After all, high street banks have spent billions building up their digital infrastructure. Startups may be learning as they go.

Potentially fraudulent methods on the way out

The good news is that hackers will struggle to find a way through the “front door”, so to speak. Open banking is built on a trusted architecture called an API (application programming interface). But there is an inferior method called screen-scraping still in use, in which the third party essentially imitates a user and goes via the consumer login. This means they need to know the consumer password in full and be able to use it in an unencrypted form.

Frans Labuschagne, head of UK and Ireland at Entersekt, a security company, says: “Screen-scraping will eventually be banned, under regulations taking effect from September 2019. But, until then, some third-party apps and websites may still rely on this method of accessing your data. Banks can’t block screen-scraping; however, they could refuse to refund fraud losses if you choose to share login details with a firm that isn’t authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority or another European regulator.”

Naturally, only the very technically minded consumer will know which apps use screen-scraping. The rest of us will go in blind.

How banks are reacting to prevent fraud in open banking

With all this in mind it is reassuring to see high street banks investing huge sums in identifying anomalous behaviour in open banking setups. Real-time analytics, for example, is at the forefront of risk reduction. Kai Grunwitz, Europe, Middle East and Africa senior vice president at NTT Security, says: “Banks need to mitigate new fraud risks by implementing controls based on advanced analytics to detect fraud attacks. Real-time risk analysis must detect abnormal behaviour in requests originating from third-party providers, identify suspicious transactions and, most importantly, detect atypical API calls.”

It is reassuring to see high street banks investing huge sums in identifying anomalous behaviour

This proactive approach can include dynamic biometrics in which consumer voice, typing and mouse movements are analysed for irregular patterns. John Erik Setsaas, identity architect at Signicat, a provider of digital identity services, says: “With dynamic biometrics, the bank can monitor usage patterns and raise flags if deviations occur. We’ve been speaking to several banks about how digital identity will make it simpler to grant and revoke access to a customer’s account, and reduce the risk of access being in any way porous.”

A new era in banking is upon us. In January, open banking was launched across the European Union, giving a new generation of service providers a chance to thrive.

At the heart of the movement is data-sharing. Open banking, under the EU Revised Payment Services Directive, or PSD2, means third parties can link up to a consumer’s high street bank account, so long as he or she consents. Mobile app Yolt is a great example. It gathers data from a consumer’s multiple accounts and provides an aggregated overview of their spending habits.

But open banking might also mean a new era of fraud. RBS chairman Howard Davies warns: “We are not confident that our customers’ data will be protected from hackers and thieves. We cannot refuse to hand over data because that’s what the legislation says, but we will have to try to educate people to understand the vulnerability.”