Throughout history, societies have used physical tokens to represent units of currency: sea shells, stones, beads, metal coins and paper notes. Increasingly, this relationship between money and material objects is being severed, a phenomenon which behavioural economics is exploring.

In 2017, card transactions overtook cash for the first time and the use of contactless payment cards doubled. UK Finance, the trade association for financial services, predicts that by 2027 cash will account for just 16 per cent of all transactions.

People pay in person using plastic cards or smartphones; they organise and move their money around an expanding universe of mobile fintech apps and can exchange it into a boggling variety of new systems of value, including virtual and cryptocurrencies.

We think differently about different sources of money

Behavioural economists have long contested the principle, expounded in classical economics, of “fungibility” or the idea that money is a neutral medium of exchange. Richard Thaler, the 2017 Nobel prize winner for economics, made the observation that people tend to treat different sources of money, earmarked for different uses, in different ways. Money, he argued, is “socialised”.

This particular cognitive bias, which he called “mental accounting”, is just one of many colouring how we interact with money. Now a number of sociologists are examining how mobile finance and new forms of virtual currency are shaping how we relate to money and think about its value. How will they affect cognitive biases?

The most fundamental cognitive bias associated with cashless payments is its dulling effect on the “pain of paying”. Behavioural economists observe that the psychological discomfort experienced when parting with money varies by medium. Contrast the pain of handing over a wad of £50 notes taken from an ATM, compared with the guilt-free ease of a frictionless one-click payment on Amazon.

“Many studies have shown that people spend more when there are fewer blocks preventing us from doing so and that our sense of the reality of the money is cut loose,” says Professor Grace Lordan, a behavioural economist at the London School of Economics.

Behavioural economics now examining the impact of mobile banking

Professor Bill Maurer, legal and economic anthropologist at the University of California, Irvine, notes that new technological platforms are socially differentiated and differentiated ways of paying that render the money associated with them similarly multiple. Age, gender, nationality and social class can be differentiators, and each comes with its own habits, codes and users.

“Different groups tend to gravitate to different payment technologies,” he explains. For instance, teenagers and young people were once the near-exclusive users of the mobile payment app Venmo in the United States, and early adopters of bitcoin were almost exclusively white and male, a profile that has grown more international, though no less male.

“Apple Pay is only available on newer and more expensive iPhones, creating a segmented market that itself is further separated for the hoi polloi of commerce because, at least in the early days, Apple Pay was only accepted at select retailers, such as the high-end retail chain Whole Foods,” Professor Maurer says in the book Money Talks.

“We’re witnessing something of a monetary revolution,” says Nigel Dodd, professor of sociology at the London School of Economics. “Money is morphing from something we have, to something we do,” he says in the same anthology. “It is becoming increasingly apparent that money is a process, not a thing, whose value comes from its qualities as a social relation.”

What behavioural economics has to say about cryptos

As the use of new virtual currencies and alternative units of exchange gather pace – J.P. Morgan in February became the first commercial bank to launch its own, the JPM Coin – behavioural economics research into cryptos is just beginning.

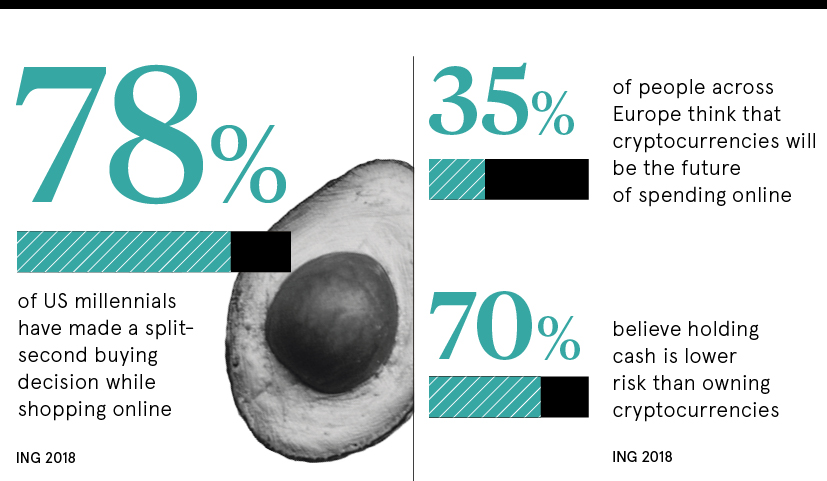

Last summer, the Dutch bank ING released a Europe-wide survey into perceptions around cryptos. While 32 per cent of people reported it is the future of investing, most considered it is a riskier investment than holding cash, gold, real estate or government bonds. ING called on behavioural economics to explain: “The average person’s perception of risk is partly based on a natural bias towards tangible and familiar assets, such as gold and property, and less about the actual degree of risk represented by a particular asset class.”

The report found that countries with lower per-capita income levels, including Poland, Romania, Spain, Turkey and Italy, seem likelier to consider paying with cryptocurrency. Bitcoin’s extraordinary surge in value between 2017 and 2018 positioned it as a way to augment earnings, according to the report.

Recent events give substance to these findings. The virtual gold in the online role-playing game World of Warcraft is now almost seven times more valuable than real cash from Venezuela, according to CNBC. Venezuela, in a desperate bid to mitigate hyperinflation, even launched its own cryptocurrency early last year.

Could AI learn how to encourage us to spend money?

Artificial intelligence (AI) presents another dimension to the debate around the use of digital currency. Could AI learn consumers’ behaviour and exploit cognitive biases to part them from their cash or be used for good?

Dr Grace Lordan of the London School of Economics notes: “When we think about money, we are affected by our emotions and our autopilot. It is quite easy to manipulate people’s behaviour.”

Professor Maurer, who is embarking on a new study into AI, funded by the credit card company Capital One, sees opportunities to help financial and banking institutions develop more responsible and fairer standards in their online services. “Social media and online behaviour may open doors to credit for the underserved, who lack traditional credit histories,” he says.

Behavioural economics is a young discipline, just a few decades old, but there are many opportunities for future interdisciplinary research.