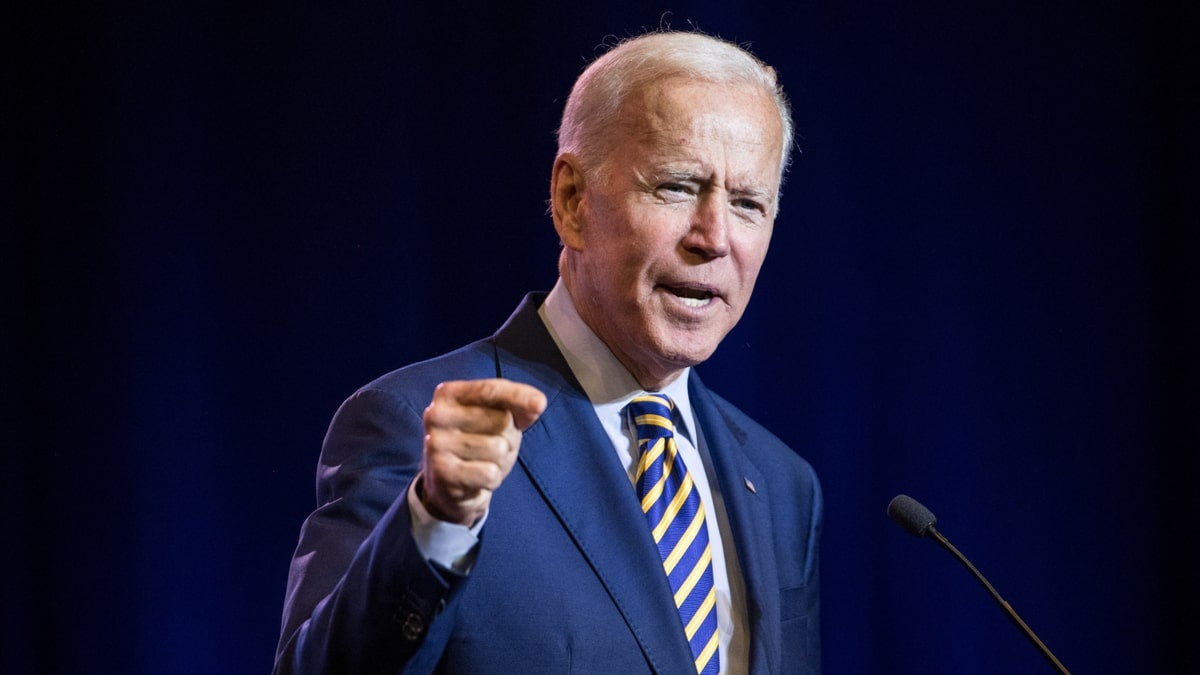

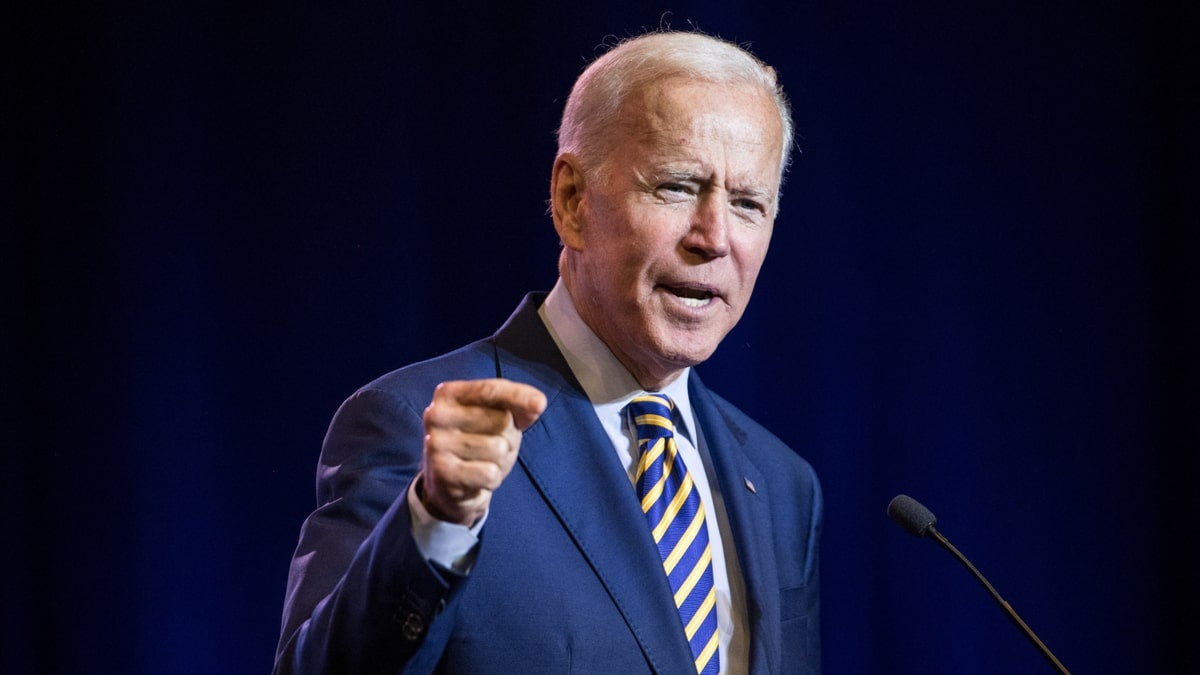

The Biden administration’s proposals for a global minimum corporate tax rate are gathering momentum, with the European Commission and, more recently, Canadian finance minister Chrystia Freeland, voicing their support for the reforms.

Outlined in April by the US treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, the plans would set a global minimum corporation tax rate of 21 percent. They would also force giant multinationals to pay tax in the countries where they sell their goods and services, instead of in the lower-tax jurisdictions to which they have routinely shifted their profits.

The Biden administration claims that its measures would end a race to the bottom in which nations have lured big businesses to their shores by undercutting other countries’ corporation tax rates. The UK’s top rate has dropped from 26 percent to 19 percent over the past decade, for instance. But getting these plans to work in practice will not be straightforward.

A ‘turning point’ for corporate taxation?

A massive upsurge in profit-shifting in recent years has highlighted the need for global coordination in reforming the system. So says Alex Cobham, chief executive of the Tax Justice Network, an independent research and advocacy organisation.

Pointing to research showing that US multinationals went from shifting about 5 percent of their profits in 1990 to 30 percent by the 2010s, he says: “You’re talking about trillions of dollars a year being shifted – a first-order global economic problem.”

The narrative shift from Yellen and Biden and their commitment to end the race to the bottom on corporate taxes is dramatic

The 37 OECD nations have been discussing how to overhaul the tax rules for multinationals for more than a decade, but Biden’s intervention should prove pivotal, according to Cobham.

“This is a massive turning point,” he says. “The narrative shift from Yellen and Biden – and their commitment to end the race to the bottom on corporate taxes – is dramatic. In 10 years’ time, we’ll look back on their pronouncements and see it as the moment things shifted.”

But much remains in the balance, as widespread cooperation will be required. There has been a commitment to reach a decision on the planned reforms by the 9 July meeting of the G20’s finance ministers and central bank governors. “There’s probably one shot at someone tabling a proposal that works, both politically and technically,” Cobham says.

The impact on Ireland

Ireland — an OECD member — has been one of the more vocal opponents of Biden’s proposals. A 12.5 percent corporate tax rate has helped the country to attract numerous multinational businesses, including Apple and Google. The Irish finance minister, Paschal Donohoe, recently reiterated his desire for “acceptable tax competition” among countries to continue.

Ian Borman, a London-based partner at international law firm Winston & Strawn, sympathises with Ireland’s cause. “There’s no moral imperative to having a high corporate tax rate. There are just alternative systems,” he argues. “All countries set their tax rates to achieve complex outcomes in the real world – these are not just dreamt up.”

Irish opposition to a global tax floor may not be enough to prevent its implementation. If the world’s largest economies — where the corporate giants make most of their profits — were to agree to the US proposals, it would remove the financial incentive for a multinational business to move to Ireland, as the company would have to pay tax in the countries where its economic activities actually take place.

What’s slightly worrying is that the Irish government appears to have done nothing to prepare for the new world that might be just around the corner

Cobham believes that Ireland “should just be left with the multinationals that are there. There’s still a value for them, as the country offers market access, human capital and infrastructure – the real stuff, as it were. In which case, if you’re Ireland, why wouldn’t you just put your rate up to 21 percent and take the tax revenue?”

He adds: “What’s slightly worrying is that the Irish government appears to have done nothing to prepare for the new world that might be just around the corner. If your entire business model is about to go, you should probably be doing some planning.”

Marcel Olbert is an assistant professor of accounting at London Business School whose research focuses on the effects of corporate taxation. He says that there may not be an immediate reaction from multinationals in Ireland should the Biden reforms be implemented.

“It’s important to remember that taxes aren’t everything,” he stresses. “Dublin is a huge hub for tech companies, so a rate change probably wouldn’t cause a mass exodus. But it will affect corporate decisions in the future, because research has shown that businesses do react to fiscal incentives.”

The global consequences

Olbert believes that territories with the strongest economic activity have the most to gain from the Biden reforms. “I think it’s logical to project that countries with large consumer markets in Europe, such as Germany, France and Italy, would benefit the most,” he says. “On a more global scale, it would mean that a lot of tax revenue could be allocated to India and China too.”

Business leaders may even appreciate the implementation of a higher standard rate of corporation tax, argues Olbert, who explains: “Many digital companies are concerned about the introduction of digital services taxes across Europe. Having different regulations between countries increases their compliance costs, so some multinationals might actually welcome a coordinated approach. Investors also like certainty, so global coordination on tax policy is probably more valuable than a slightly lower rate to corporate decision-makers.”

But James Mastracchio, partner and co-leader of Winston & Strawn’s tax controversy practice in Washington DC, believes that it would be highly unlikely that the reforms, if implemented, would produce all the outcomes desired by their proponents.

He says: “Even if we went to a flat tax, there are too many tentacles for that to be a simple change. If governments want to incentivise certain industries, they can provide tax breaks. For example, tech companies get a favourable outcome when they invest in R&D. There are lots of competing concerns, so something that may look very simple would, in fact, be enormously complicated.”

The Biden administration’s proposals for a global minimum corporate tax rate are gathering momentum, with the European Commission and, more recently, Canadian finance minister Chrystia Freeland, voicing their support for the reforms.

Outlined in April by the US treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, the plans would set a global minimum corporation tax rate of 21 percent. They would also force giant multinationals to pay tax in the countries where they sell their goods and services, instead of in the lower-tax jurisdictions to which they have routinely shifted their profits.

The Biden administration claims that its measures would end a race to the bottom in which nations have lured big businesses to their shores by undercutting other countries’ corporation tax rates. The UK’s top rate has dropped from 26 percent to 19 percent over the past decade, for instance. But getting these plans to work in practice will not be straightforward.