Ten years after the global banking crisis and alternatives to the systems that caused it are still sought. For techno-libertarians and anarcho-capitalists, who would gladly see feckless banks and inefficient governments done away with entirely, one fintech solution is posed by the digital cryptocurrency bitcoin. Underpinned by a distributed ledger known as blockchain, bitcoin would allow finance to flow freely without third-party governance or oversight simply by following the laws of code.

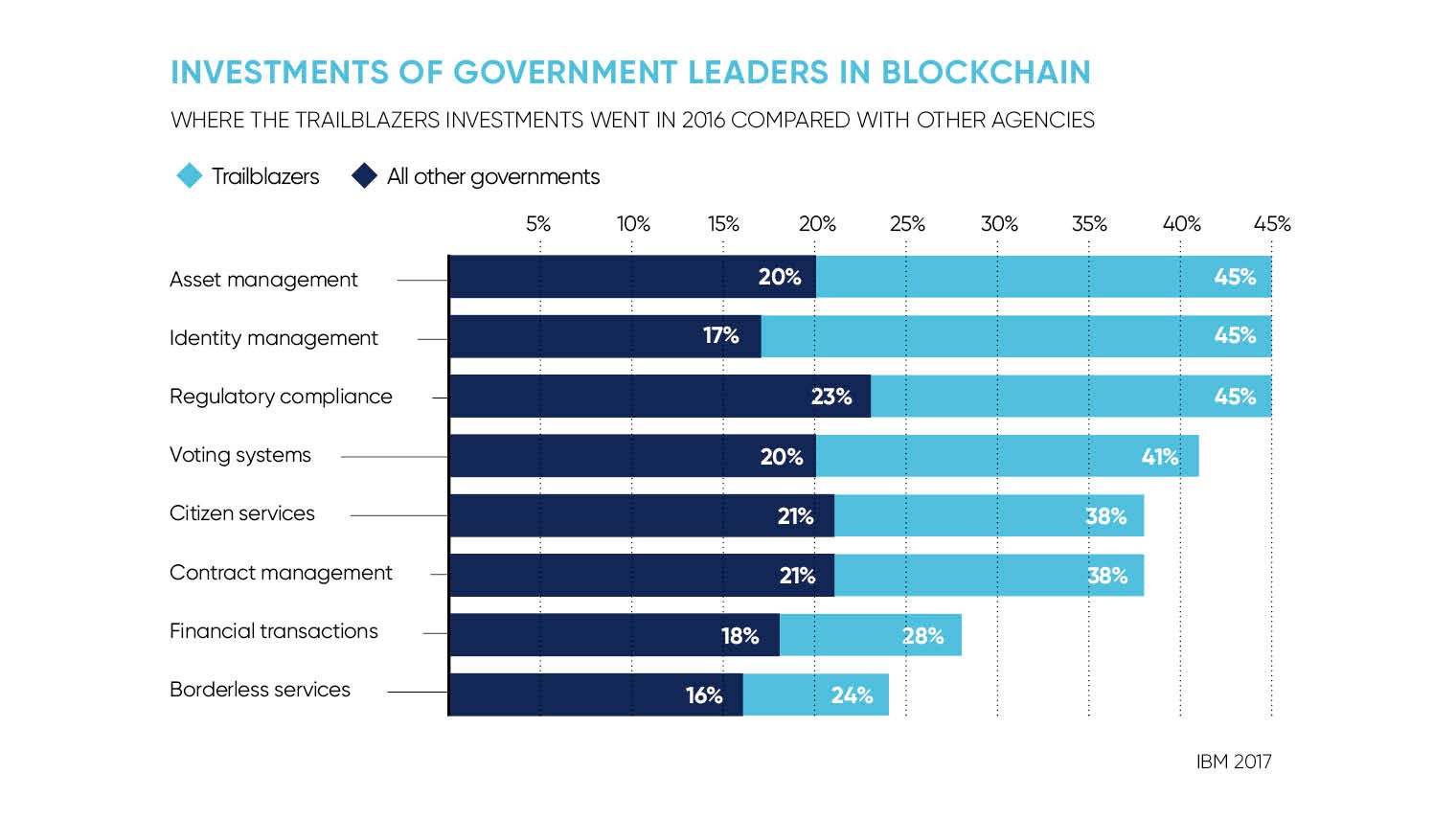

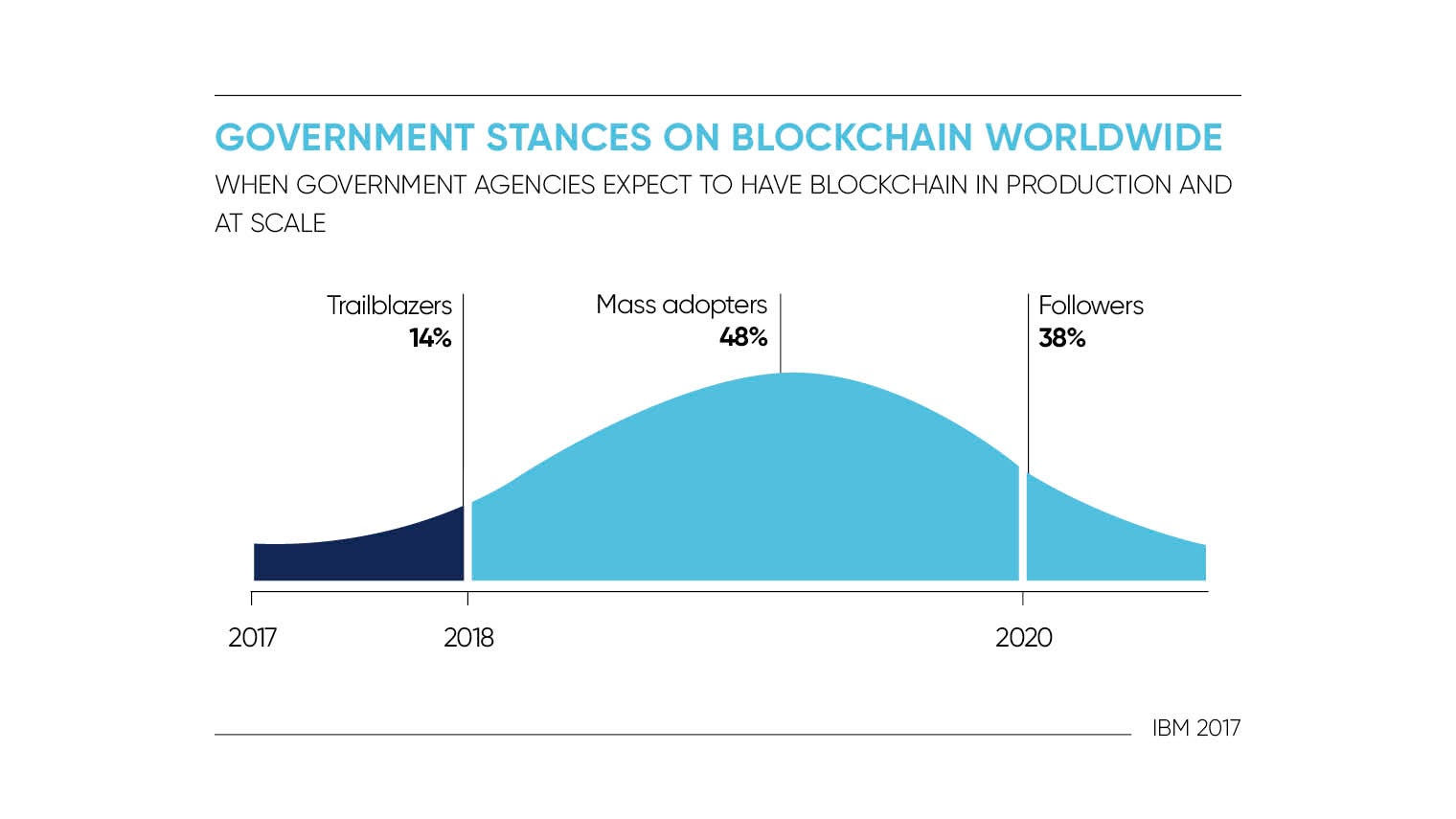

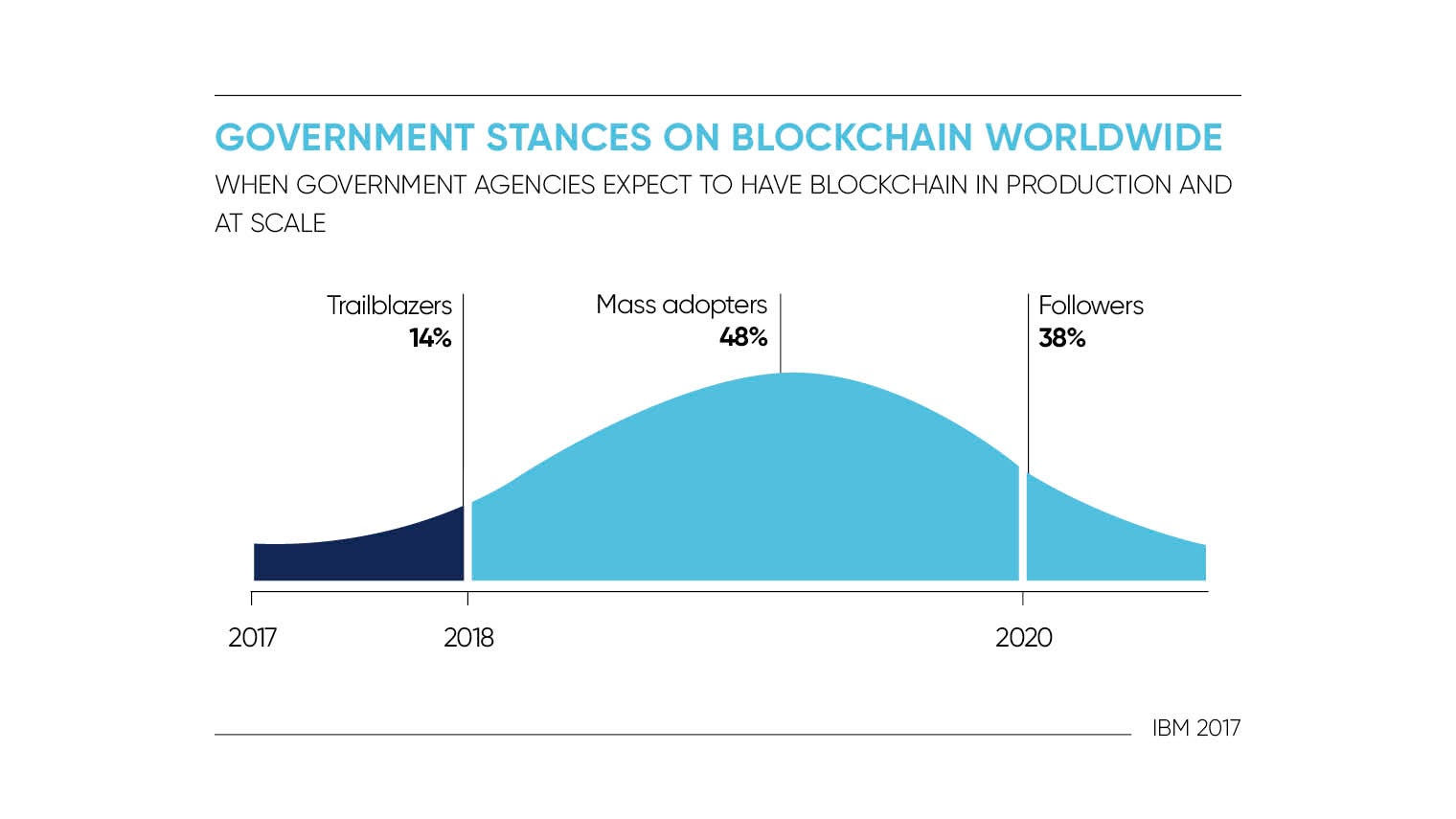

It is an ironic twist of fate, then, that far from seeing central authorities toppled by blockchain, governments are expected to be the main drivers of its adoption. By 2018, nine out of ten government organisations plan to invest in blockchain technologies to help manage financial transactions, assets, contracts and regulatory compliance, according to a recent IBM survey.

Which begs the question, what is blockchain and why do governments consider it important?

As a type of distributed ledger, a blockchain is a database that is maintained by a number of its users collectively rather than by a single entity centrally. Changes made to the ledger are encrypted so they cannot be changed or erased without leaving a record at every stage. In theory, any kind of data, from health records to business transactions, can be added to a blockchain, creating permanent and secure records. For that reason, it is considered a powerful potential tool for improving transparency, efficiency and trust.

Proponents believe blockchain has potential in almost any context where information needs to be agreed and shared, for instance insurance, trade deals, public health systems, foreign policy, international aid, taxation, loans – the list is seemingly endless. It follows as little surprise that governments are exploring the area as part of their wider digitisation efforts for fear of losing a competitive and strategic edge.

“There are going to be clear winners and losers,” says Dr Catherine Mulligan, research fellow at the Centre for Cryptocurrency Research and Engineering at Imperial College London. “It is not necessarily about which governments are investing, but those that are enabling support for these kinds of technologies will see a significant advantage.”

Blockchain has the potential to be many things to many people, and how it is fostered by different governments will largely depend on their political bent and organisational needs

A fundamental difference between private and public blockchains should be made clear. Public blockchains follow the original anarcho-capitalists’ ideal which requires no oversight and allows anyone to join the network and to contribute to it, and for anyone in the world to see its records. Private systems, by contrast, which are the kind sold as blockchain-as-a-service (BaaS) products by companies such as IBM and Microsoft, are closed and include an administrative structure.

“The technology is political and can serve both philosophies very well,” says Tomaso Aste, professor of complexity science and head of the financial computing and analytics group at UCL.

Blockchain has the potential to be many things to many people, and how it is fostered by different governments will largely depend on their political bent and organisational needs. Are they a progressive liberal democracy or a one-party state? Do they suffer from high levels of corruption? Are their bureaucracies co-operative or divided?

UK government departments, for example, are beleaguered by data-sharing problems and silos caused by departmental differences in organisational culture and the demands of their respective data sets. IT procurement in UK government departments is wrought with difficulty, pegging the country far behind front runners like the leading e-nation Estonia, where almost all government services are accessible digitally.

The UK fares slightly better in central banking tech research. The Bank of England, which has been researching blockchain for several years, recently announced the successful test of an interledger programme developed by Ripple, the California-based blockchain specialist, to synchronise a payment between two central banks’ systems.

However, no government is doing more research into blockchain applications at scale than China, which has developed its own cryptocurrency, trialled a blockchain taxation system, and hopes to establish itself as a global leader in the sector, according to Cai Weide at the blockchain research institute in Qingdao. China’s latest move, however, has surprised many in what appears to be the shutdown of the country’s cryptocurrency exchanges.

Imperial’s Dr Mulligan notes that the Chinese government is very likely to be interested in the ability to track and trace every transaction made in its economy and records added to government databases. This poses the question could blockchain be used as a tool to aid surveillance of citizens and by extension as a means of suppression? China has a partly managed economy and an ambivalent attitude to human rights as a one-party authoritarian state. Just imagine pairing the power to have immutable records on your citizens with future technologies enabled by artificial intelligence, such as biometric surveillance. The vision is Orwellian.

This future may never materialise, according to Vili Lehdonvirta, economic sociologist and associate professor and senior research fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute, because most blockchain talk sets unrealistic expectations for the technology and is founded on unsubstantiated hype. “Let me put it this way, have they [BaaS providers] come up with a single client that is actually using it for something other than a prototype? Most of these problems people are seeking solutions to are organisational science problems,” he says.

Technology is a tool and rarely a silver bullet, however much we may will it otherwise. Even if blockchain were to become a kind of digital philosopher’s stone, at least the race it will have triggered to make government services and activities more efficient, transparent, consensus-based and trustworthy will have caused decision-makers to begin thinking imaginatively and talking seriously about pursuing these goals.