Cyberattacks are no longer limited to the unlucky few, but have become worryingly common. And now, in addition to ransomware, the usual source of denial-of-service attacks, there is another, low-key form of criminal assault spreading in cyberspace.

Rather than locking down systems until their ransom terms are met, some hackers are prepared to play a longer game with a valuable prize in their sights – cryptocurrencies.

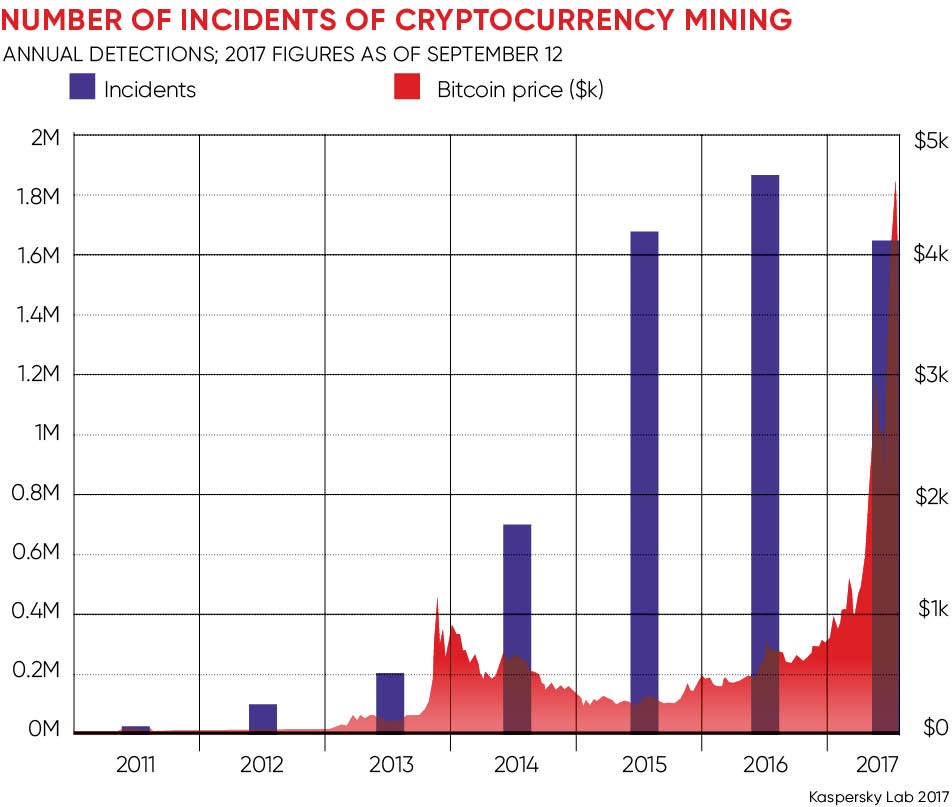

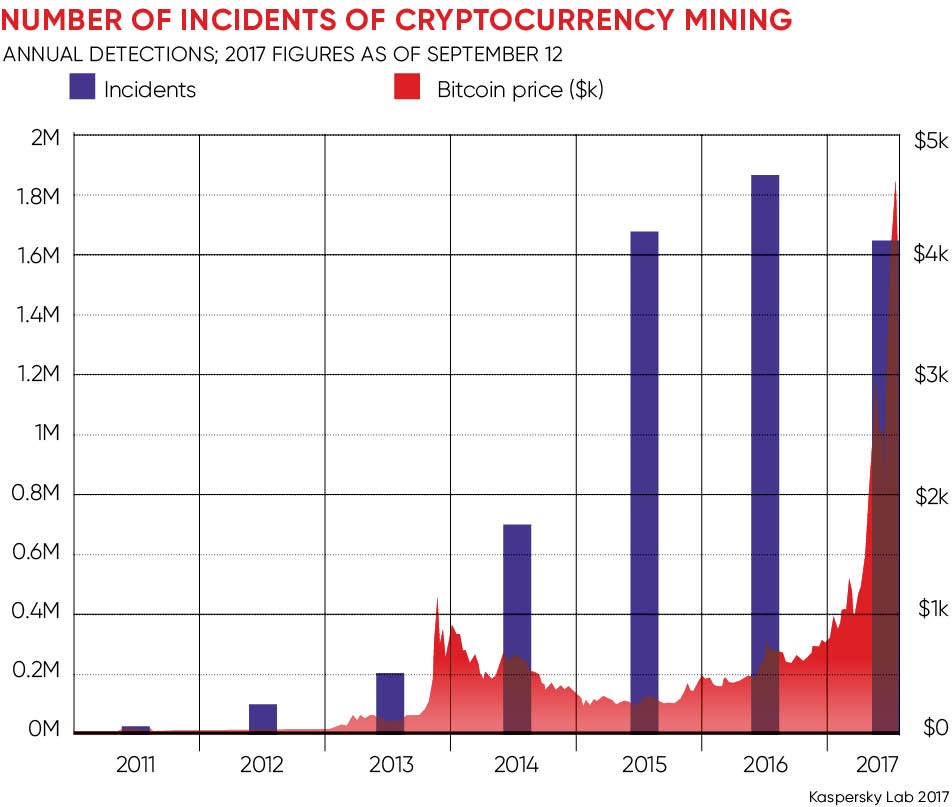

This is because cryptos have become so lucrative, with bitcoin increasing by more than 900 per cent and ethereum by more than 2,500 per cent so far in 2017.

The attack goes like this: hackers seek to infiltrate a company’s systems and capture a small portion of its computer processing power to “mine” for coins, a process called crypto-jacking.

Mining cryptocurrencies is the backbone that enables cryptos to function. New coins are created as a reward for miners who secure and verify payments in the blockchain where cryptocurrency transactions are recorded.

Mining cryptocurrencies involves being rewarded for the processing of extremely complex mathematical problems

This has become incredibly capital intensive in recent years, requiring huge amounts of processing power with a corresponding huge electricity bill. So there’s ample reward for hackers to use other people’s machines to mine coins.

To put this in perspective, Citibank has estimated that bitcoin will eventually consume as much electricity as the whole of Japan. Meanwhile, cryptocurrency analyst Alex de Vries has created an index which shows current bitcoin energy consumption as being equivalent to that of Serbia or almost 10 per cent of UK usage, which means the power used for each transaction could power a home in the United States for a week.

As the price of cryptocurrencies has shot up, so has the use of mining malware. Russian internet security firm Kapersky Lab says it has detected 1.65 million incidents of malware mining so far in 2017 on top of 1.8 million in 2016.

“Over the last few years we have seen a large increase in availability of complex malware which has fuelled the number of cyber-incidents in general,” says Devina Patel, an account executive in the cyber and technology, media and telecommunications division at Willis Towers Watson.

Though the most likely to be attacked, larger firms are also best prepared and there are others who should take note of the threat.

“Companies that should be wary of this risk are the small to mid-sized businesses that have often been targeted with the knowledge their defences won’t be state of the art,” warns Ms Patel.

The education sector, particularly universities with research facilities that use powerful supercomputers, should be mindful of the risks as they may be unattended during certain times of the year.

That doesn’t mean large organisations don’t need to increase their vigilance. Both Equifax and Uber have recently announced major breaches and they won’t be the only ones. Utilities have considerable computing power, but on ageing systems, while local authorities, hard pressed to cut costs, may have compromised their IT security.

However, even financial services organisations can find mining malware on their systems, says Martijn Verbree, a partner in KPMG’s cybersecurity team.

“It is not necessarily on a machine that is directly connected to the internet, but a network server that was used for Christmas party photos from years ago and has been forgotten about,” he says.

Disrupting mining malware is not difficult, says Mr Verbree, as it can often be stopped with the use of an ad-blocker. Discovering that you have it is another matter because it’s designed to be unobtrusive, so you need to be watching all the time.

“You have to get back to basics and understand what is in your network, what is hanging off your network, and you need to scan these boxes for nasty surprises,” he says. Ensuring software is up to date, patches are in place and passwords being used are neither the default nor too simple is half the job done.

The Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2017 shows that despite security being considered a high priority (93 per cent) among senior management, the government’s recommended ten steps for cybersecurity are being applied in a piecemeal fashion.

While 92 per cent of businesses update software when it is available, 90 per cent maintain up-to-date malware protection and 89 per cent maintain firewalls with appropriate protection, only 30 per cent offer training to their staff and 11 per cent have a formal incident plan in place should there be a catastrophic breach.

Access is the name of the game and “whitelisting” sites considered safe, limiting media content and blocking JavaScripts all help to prevent web browser-based attacks, says Ms Patel. In addition to regular updates, companies should monitor computer central processing unit performance for any spikes and start off with a baseline of what “normal” looks like.

“If companies are able, they should be using intrusion detection and prevention systems that look at the number of connections being made, where they are going to and come from, and the amount of bandwidth each connection is using,” she says. “This way anomalies can be detected and analysed in much more depth.”

Not every business needs 24/7 cyber-watchdogs patrolling their networks. Each business should balance the risk against its resources and determine an appropriate response.

However, employees – the most important element of cybersecurity breaches – are all too often overlooked, and worryingly few businesses focus on user education and awareness of the risks.

“It needs to be ingrained in the workforce that they all play a part in cybersecurity,” says Ms Patel. “Employees need to be thinking carefully before clicking on unknown links or allowing any downloads on to their systems.”

That needs to include mobile devices and where they are used, she says, yet only 23 per cent of businesses have a policy on mobile working and 22 per cent on what may be stored on removable devices.

Businesses may find their cyber-risk insurance will cover losses, but the insurance industry is keeping an eye on its development.

“We see a lot of breach cases where the hackers are not interested in data, but want access to hardware,” says Neil Gurnhill, chief executive of specialist cyber-risk insurer Node International.

“Like most evolving risks, we don’t identify mining malware specifically, but I imagine we will.”

The current treatment for mining malware is straightforward for those maintaining basic IT hygiene. However, the growth of cryptocurrencies threatens further development of more sophisticated attacks, which may not bring down the company, but leave a door open for those who would choose to do so.

Businesses must be prepared, and be seen to be prepared, to be mitigating these risks vigorously.