For investors Hong Kong has long been the global financial system’s friendly go-between with China, now the second-largest economy in the world. Smooth running money markets, an independent legal system, a lively independent press and free speech has seen freewheeling capital muscle in and talent flock to the former British colony for decades. But times are changing.

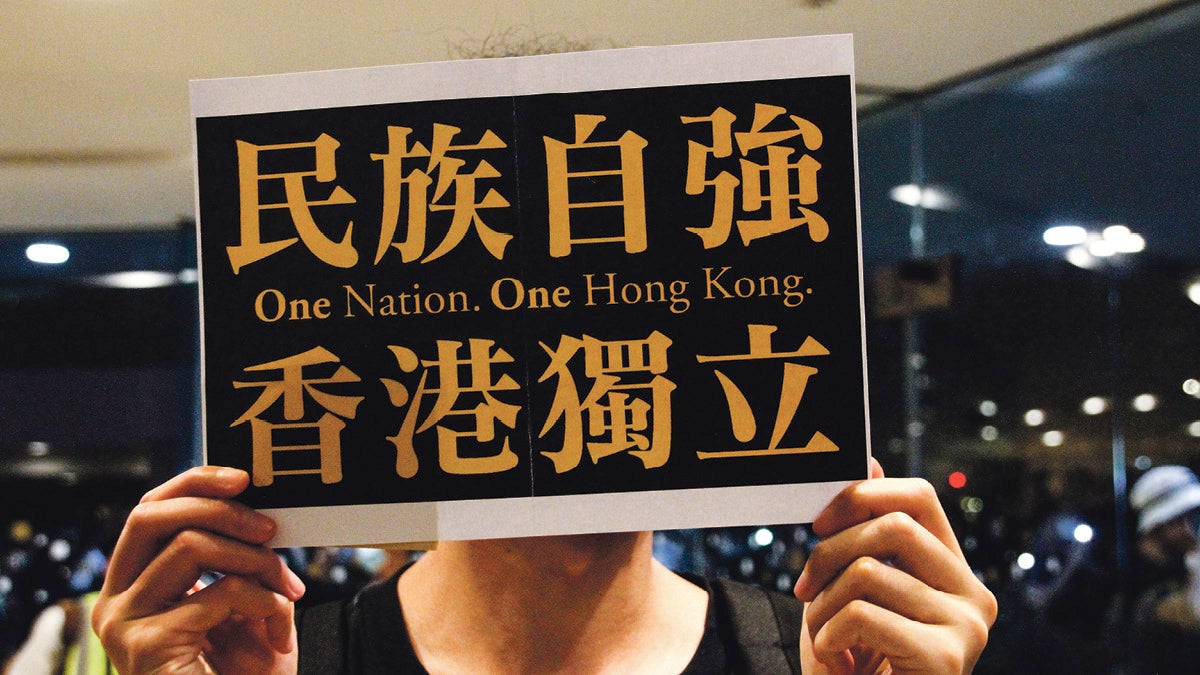

After a year of social unrest, the apparatchiks in Beijing are fed up, imposing a sweeping new national security law on a territory that was supposed to have semi-autonomy with a “one country, two systems” approach until 2048. The law will ban subversion, secession and sedition.

Hong Kong’s position won’t be eroded overnight, but without assurances…overseas firms will over time shift their operations elsewhere

This evolving relationship between Hong Kong and China has fired up geopolitical tensions with the West, raising concerns among global traders. Now the potential for flight of capital is palpable.

“China is settling into a more antagonistic relationship with the rest of the world. Hong Kong’s position won’t be eroded overnight, but without assurances that companies and staff there will enjoy strong legal protection and aren’t subject to the arbitrary treatment found on the mainland, overseas firms will over time shift their operations elsewhere,” says Mark Williams, chief Asia economist at Capital Economics.

Confidence in Hong Kong’s reputation as a global financial centre for investors seeking exposure to China’s vast markets and companies has taken another blow after America said it’s seriously considering measures to restrict money flow through the territory. Meanwhile, the British government says the new national security law is a clear violation of China’s international obligations. Tensions have been raised.

All this could hurt Hong Kong. The region is Asia’s third-largest capital market, nine of China’s ten most valuable companies are listed there and two thirds of the funds China raises overseas are channelled through the city. It’s also a gateway for investors in China’s $10-trillion bond market. And the currency that speaks the loudest is not the renminbi (RMB), but the greenback.

“I think it’s in the best interest of China to keep Hong Kong as its buffer zone. It’s also in the best interest of foreign powers not to ruin Hong Kong’s special status. But I hope with this new law we can restore stability, because protestors have collapsed the city’s ‘can-do’ spirit,” says Ronald Chan, chief investment officer at Chartwell Capital.

A demonstrator waves a black flag during June protests marking the first anniversary of a historic march against the extradition bill

A safe pair of old China hands

This global financial centre has historically been one of the world’s safest and most efficient places to trade, despite protests, clashes and tear gas. As international markets go, Hong Kong is as free as you can get. This city on the Pearl River delta has also helped China reach out and liberalise its financial markets with the Stock Connect scheme.

“Equity prices in the broader China market and Hong Kong specifically are more attractive than the average. However, it’s worth noting that these markets are both volatile and this volatility may increase during the current political situation,” says Dan Kemp, chief investment officer, Europe, Middle East and Africa, at Morningstar.

Yet Hong Kong is also the ultimate survivor. Braving the 1997 handover to China by Britain and Asian financial crisis, its banks were also largely unscathed by the global financial crash of 2008. It’s maintained some of the lowest taxes in the region and is one of the largest wealth management centres in Asia. The relationship between Hong Kong and China is buoyed by meteoric economic growth rates on the mainland.

Smart money also still needs a place, with enough capacity and sophistication, to park and grow. This is why Hong Kong remains attractive.

“It is very possible that the new national security law for Hong Kong will reduce risks. For instance, insurers and long-term real estate investors should now have a clearer view about trends post-2048, which could be beneficial as they look to invest long-term capital,” says James Tunkey, chief operating officer at I-OnAsia, a risk management consultancy.

The biggest fear that Hong Kong has always had is that if trading isn’t competitive then business will go elsewhere. It’s arch-rival Singapore, hardly a bastion of free speech and democracy, continually nips at its heels. If you remove Hong Kong’s autonomy and its impartial legal system, then you might as well invest in Shanghai. Now the wild card is how President Donald Trump’s America deals with China in this presidential election year.

Were Chinese companies delisted or refused listing in New York, they may think twice about Hong Kong

“The US cannot act unilaterally to revoke Hong Kong’s special status, but it can create significant difficulties for how mainland Chinese companies using the territory’s markets are perceived by investors. The US’s pursuit of Huawei is an example of the type of non-tariff measures America could pursue,” says Dr Damian Tobin, researcher at the Cork University Business School.

“Hong Kong has long offered mainland Chinese companies a route to external capital and this market would be jeopardised by any perception that its markets are no longer independent. For example, were Chinese companies delisted or refused listing in New York, they may think twice about Hong Kong. Remember this is not about valuations since these are typically much higher in Shanghai.”

An issue managing two systems

Hong Kong’s use to China is also to do with the US dollar funding it supplies; there is no mechanism China has to replace this right now. The issue is whether Beijing is willing to risk damaging this and the very foundations of the former British colony’s success to assert greater control.

But if investors believe the new national security law will bring stability, they may have to think carefully. There’s more at stake than slick money markets and juicy returns. An uncertain element in this power play is the Hong Kong people themselves. Having to navigate the one country, two systems they inherited from the colonial era may just be too much for the territory’s politicians. It doesn’t help that ordinary people aren’t seeing much in the way of economic prospects either. Here may lie the answer.

“The issue at stake is a persistent decline in governance. There is little attention given to this issue. From Beijing’s side the security law reflects a failure by Hong Kong’s politicians to read the public mood and manage the tensions associated with managing and regulating two systems,” explains Tobin.

“It’s not just to do with financial markets. There is a failure to find an effective way of ensuring benefits flow to the wider society. The daily volume of Hong Kong to Shanghai financial flows increased from just over RMB5.5 million in 2017 to 21 million in the first three months of 2019, but this has had a very limited impact on living standards for a large swathe of Hong Kong’s residents.” Trading strategists take note.