Fintech, the global phenomenon of finance melded with technology to make banking less like banking and finance services more accessible, seems to have an endless capacity for traction the whole world over. Agile startups and incumbent businesses work together or lock horns in a battle for dominance over one of the most lucrative markets.

But although fintech markets continue to pump out riches for those who can appeal to a broad customer base – big four accountancy firm KPMG says fintech deals in the first quarter of 2017 alone hit $3.2 billion – the bigger challenge is turning fintech into a tool that can help bring access to finance to the world’s two billion people who don’t have a bank account.

Banking the unbanked

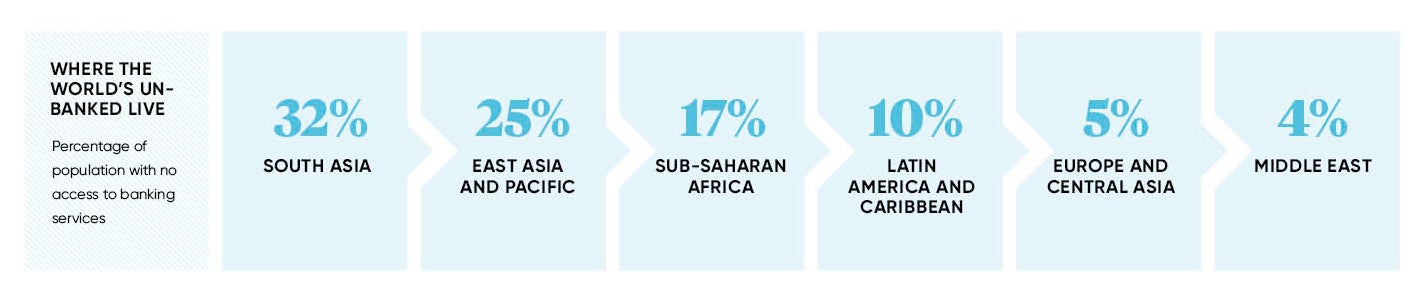

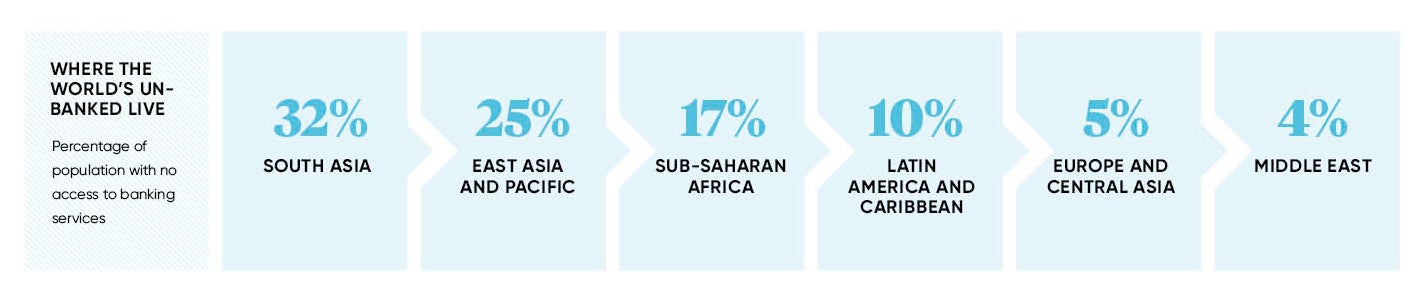

While the number of unbanked people has fallen in recent years, those without access to banking services overwhelmingly come from poorer countries. In fact, 73 per cent of the world’s unbanked citizens come from just 25 countries, including India, Brazil and China.

“There are a number of fintech initiatives [for developing countries] and some are longer lived than others,” explains Bernardo Batiz-Lazo, professor of business history and bank management at Bangor University in Wales. “Some of them are private companies and some are government supported, which illustrates how big and broad the term fintech is.”

For Professor Batiz-Lazo, one of fintech’s biggest draws in poorer countries is the ability to make the transfer of money safer and reliable. For workers living outside the banking system, who are accustomed to getting paid in cash, the journey home through cities with high crime levels can be dangerous, and electronic transfers and payments minimise the risk of cash being lost or stolen.

Some of the biggest successes for fintech in developing countries have been in African countries, including Kenya, Zimbabwe and Botswana, where services such as M-Pesa – a decade-old money mobile service produced by Vodafone – have been hugely popular. Now going into its second decade, M-Pesa boasts more than 30 million users across the continent and, last year, processed some six billion transactions. It is particularly popular in Kenya, where it is used by 17 million people, and estimates suggest that 25 per cent of Kenya’s GDP flows through the app.

But for Professor Batiz-Lazo, M-Pesa can only be successful where banks are less so, limiting its scope to empower unbanked peoples in other countries. “M-Pesa is just monetising air time,” he explains. “You top up your mobile phone, or you do it the over way around, and the balance that you have in your mobile phone account has the advantage of being shareable.

“M-Pesa hasn’t worked in South Africa because, as a country, South Africa has a much bigger and deeper banking infrastructure. When they tried to use the system there, it didn’t pick up. In places like Botswana, or Kenya, you are still seeing a process of migration from rural areas to cities. People used to send cash by hiring taxis to send their money, but often not all of it arrived.”

The bigger challenge is turning fintech into a tool that can help bring access to finance to the world’s two billion people who don’t have a bank account

New apps, however, are being delivered all the time. In developing-world fintech, September was a big month as Indian finance minister Arun Jaitley declared that Tez by Google, a new fintech app that transfers money using sound, would make “a major change in the digital payments landscape across India”.

Unlike other apps, Tez – taken from the Hindi word for fast – isn’t exclusive to more-expensive smartphone models with near-field communication chips. This means Tez, coupled with its ability to process payments between banks, will bring more of India’s 300 million smartphone owners into the finance system.

Yet despite projects such as Tez, and there are many others of varying sophistication in Asian countries including Pakistan and Bangladesh, Professor Batiz-Lazo is sceptical about fintech companies’ capabilities when it comes to being world-changing forces of financial empowerment. One of the reasons for this, he says, is consumer choice not to adopt fintech, with people in developing countries preferring to stick to cash payments.

“The question is why aren’t people using it?” he asks. “It’s not an issue of technology, there is a lot of very good technology out there – people are just not adopting it.

“Sure, Alipay and WeChat from China have outstanding numbers of users,” he says, “but what nobody has shown is how many of those users are in coastal areas and how many are in rural areas. Here we are talking about two very different economies in China and also two very different attitudes to payment.”

Other organisations are more enthused about achievements of fintech projects in the developing world. The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) finds that fintech companies in Asia, such as bKash in Bangladesh and now Tez in India, have had positive impacts on local banking sectors. In particular, bKash which has been adopted by 17 million Bangladeshis, in a country where 70 per cent of adults are unbanked, has made tremendous progress. Still, the IFC concedes that globally there remains room for more progress.

Banking the unbanked