After they sell a business, entrepreneurs typically want to start a new one. Or act on that long-delayed dream of buying a yacht and sailing around the world.

Both sound like great plans that may have to be postponed as the seller of a company may not immediately receive a significant chunk of the proceedings.

The reason is the buying party may demand the entrepreneur provide financial guarantees that no unexpected liabilities will impact on the value of the business after the deal is closed. Such as a tax bill that was not properly filed, an infringement of intellectual property previously undetected or a fine for environmental damages unwittingly perpetrated by the firm a few years before.

The matter of who pays for future liabilities is often a sticky point that has brought many a deal to a standstill

This kind of liability can reach millions of pounds in value, and investors are rightly worried in times when states’ regulatory activities are on the rise. The matter of who pays for future liabilities is often a sticky point in M&A negotiations that has brought many a deal to a standstill. But the insurance market has spotted an opportunity to come up with a solution that has gained evermore acceptance in the market in recent years.

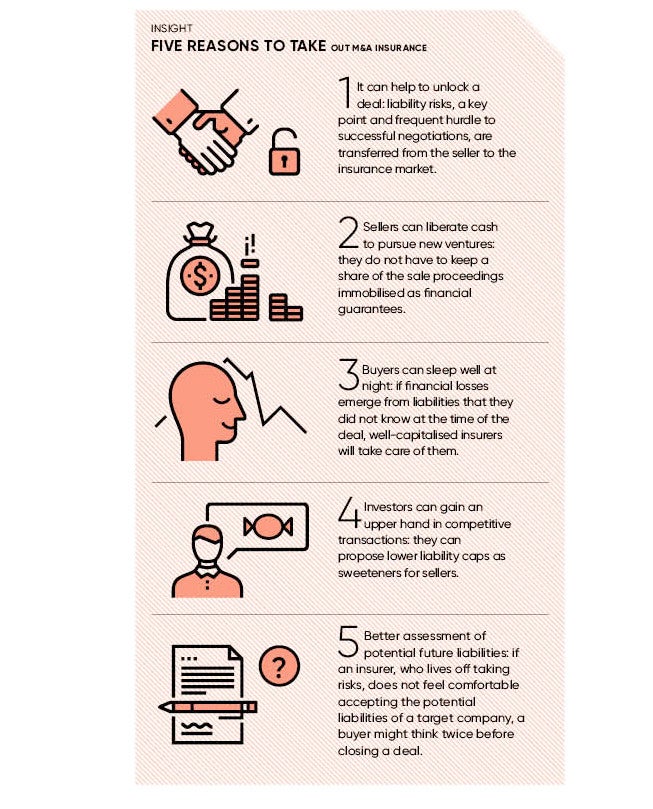

M&A insurance coverages, the most common of which are known as warranties and indemnities policies, or simply W&I insurance, have become a tool employed by both parties of a deal to smooth up negotiations by taking a significant chunk of risk off the table.

“A W&I insurance policy gives the buyer security and lets the seller use the money immediately,” says Brian Hendry, head of M&A at London-based brokers Paragon.

The policies cover the risk the buyer could face in the future, financial losses in areas such as tax, regulatory issues or pensions that were not disclosed or spotted by due diligence at the time of the deal.

Cover is based on the information provided by sellers in the sales and purchase agreement that seals the deal. This information is expected to provide an accurate picture of the state of the business and buyers will often demand that sellers show their good faith by backing it up with a slab of their own money.

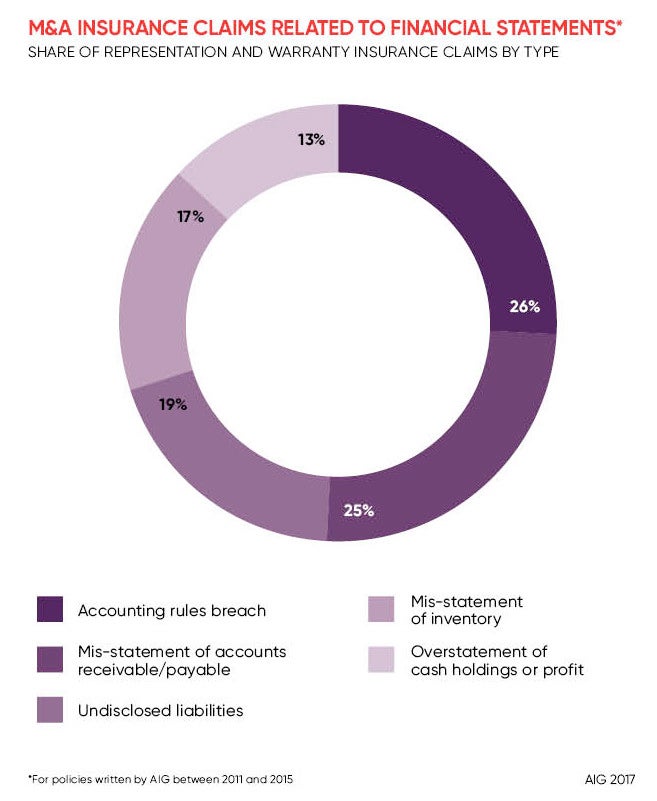

The potential for disputes after a deal is closed has been vividly illustrated by the well-reported squabbles between Hewlett Packard and the former owners of Autonomy. HP bought Autonomy for £7.4 billion in 2011, only to later claim that accounting issues and other problems had not been disclosed during the negotiations.

To avoid this kind of headache, buyers often demand the tabling of financial guarantees, such as the deposit of a share of the company’s value in an escrow account for, let’s say, a period of 18 months. In cases where risks are seen as quite significant, buyers may demand that sellers put aside up to 50 per cent of the company’s value.

This has never been a satisfactory situation for private equity firms that are eager to pocket the cash earned with a sale and redistribute it among fund investors or reinvest it in another purchase.

“For a financial investor, putting money in an escrow account is not a very good use of money,” Mr Hendry points out.

In some cases, litigation can take place well beyond the agreed period for the financial liabilities. Tax liabilities provide an example as they can last up to seven years. Especially in the case of businesses purchased from individual entrepreneurs or families, the money to be recovered through the courts may no longer be available after such a long time, warns Ben Crabtree, a partner at brokers JLT Specialty.

W&I insurance solves this problem by transferring the responsibility of coming up with indemnification for eventual liabilities to a well-capitalised underwriter.

According to data analysed by JLT, W&I policies cover on average 28 per cent of the value of the enterprise, in the case of liability after the sale. That amount is enough to soothe the fears of many investors, clearing the path for the final shaking of hands.

“W&I policies have become a staple in M&A deals and companies have been using them to manage their transaction processes,” says Will Hemsley, a partner at brokers HWF. “Deals are a lot slicker when buyers and sellers are not arguing about key points, as risks have been passed on to the insurance market.”

Market players point out that transactional insurance started as a product aimed at private equity investors in the late-1990s, but in the past few years has also been used by corporations and family-owned businesses to oil their deals.

A decade ago, only a handful of insurers offered coverage. Now, according to Mr Hendry, more than 35 underwriters are active in the sector. As a result, prices have dropped and conditions have improved for policy holders. The cost of a policy in the UK ranges between 0.9 per cent and 1.3 per cent of the policy limit, brokers Paragon estimate.

Mr Crabtree, for his part, notes that W&I has developed to an extent that it has become a strategic tool that parties in M&A transactions employ to gain an upper hand in negotiations.

For instance, when a company is sold at an auction and the expected price of the transaction is already known, a bidder can demand lower levels of financial guarantees from the seller by using insurance to transfer liability risks.

“One bidder can employ insurance to reduce the seller’s liability cap to 1 per cent of the value of the transaction and have an advantage over another who demands 25 per cent of the value as a financial guarantee,” says Mr Crabtree.