The TV industry is in the grip of a series of mega-mergers. Leading the way is AT&T’s proposed $85.4-billion (£62.5-billion) acquisition of Time Warner, which would turn the telecoms giant into a content behemoth, with properties ranging from superhero franchises to CNN and Harry Potter to HBO. Although the deal was blocked by the US Department of Justice on public interest grounds, AT&T is challenging the move in court.

Next is Disney’s blockbuster $52.4-billion (£38.3-billion) acquisition of most of 21st Century Fox, a deal that has since been complicated by NBCUniversal-owner Comcast’s $31-billion (£22.6-billion) offer to buy Sky, of which Fox owns 39 per cent.

Meanwhile, Vodafone has joined the fray with an $18-billion deal to buy European cable networks from Liberty Global. Then there’s CBS’s still-in-the-balance reunion with Viacom, whose brands include Paramount Pictures, MTV and Nickelodeon.

With media mergers and acquisitions in the works, television is in an unprecedented state of flux

With other media mergers and acquisitions reportedly in the works, television is in an unprecedented state of flux. This protracted game of media musical chairs is being driven by four main forces. First, the traditional TV business model is not so much ailing as in intensive care: TV advertising is predicted to fall behind digital for the first time this year, according to Dentsu Aegis, while Google and Facebook are carving up an ever-increasing share of the pie.

Second, over the top (OTT), where content is streamed over the internet, is on the march. In 2014, OTT accounted for just 10 per cent of the total US video industry value capture. Boston Consulting Group predict this will double in 2018, a figure which represents more than $30 billion (£22 billion) in revenues in the United States alone. The success of streaming player Roku also suggests a tipping point is on the horizon. In 2015, Roku users streamed 5.5 billion hours of content. By 2016 that number had risen to 9 billion. In the first half of 2017 alone, users streamed 7 billion hours, representing 61 per cent year-on-year growth.

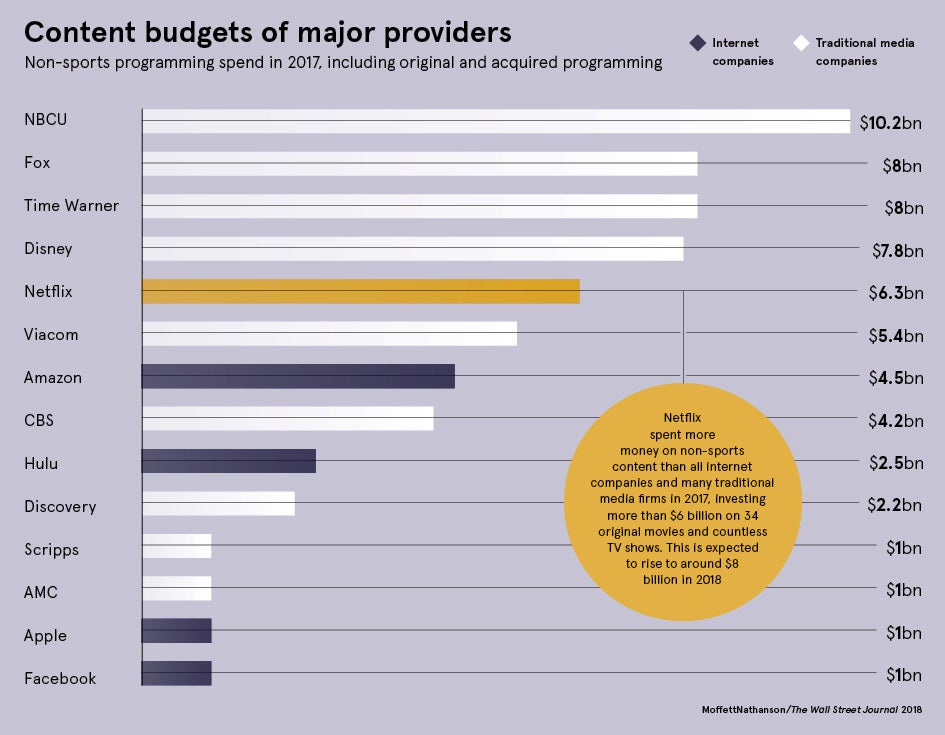

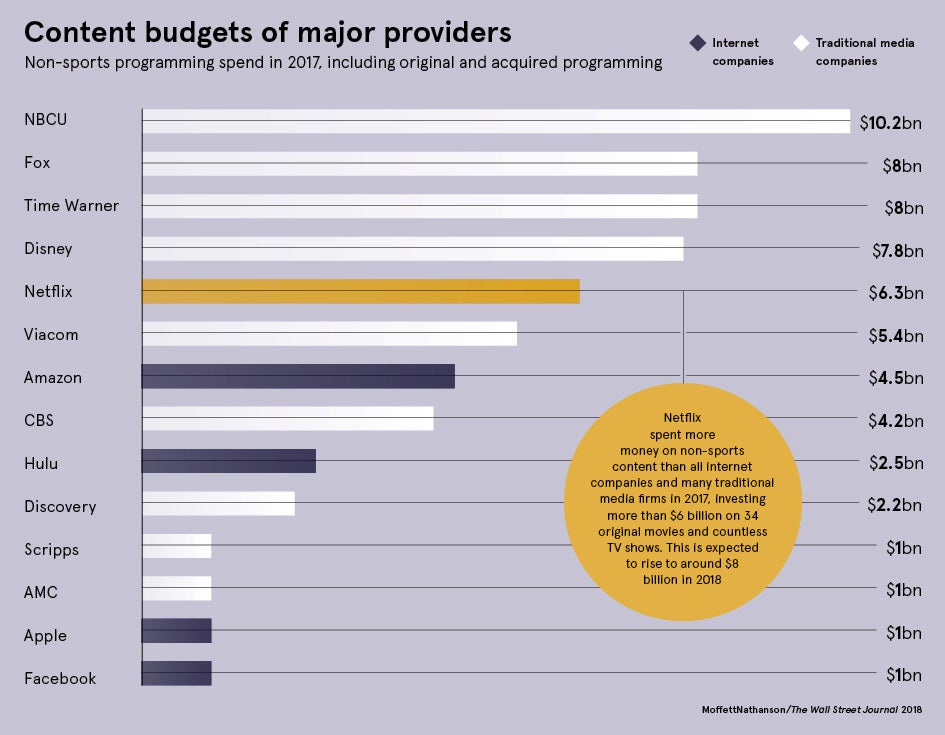

Then there’s the irresistible rise of the technology superpowers and of Netflix in particular. Since launching 20 years ago, the monster streaming service now has 125 million subscribers in 190 countries. Wall Street bank Piper Jaffray predicts it will reach 160 million by 2020, while Netflix says it will spend $7 billion to $8 billion on content in 2018. That level of spending places Netflix ahead of competitors such as Time Warner’s HBO and Hulu. However, Netflix isn’t the only tech player disrupting TV as it’s estimated by J.P. Morgan analysts that Amazon spent some $4.5 billion (£3.3 billion) on original content in 2017, while Apple plans to spend about $1 billion (£733 million) this year.

So if these forces provide the backdrop, what impact will they have on the future TV landscape?

As we close in on the era of “streaming by default”, it’s now clear that alongside the major tech players, OTT will favour those corporates with the brand clout and content muscle to win market share. Disney is exhibit A. Ahead of pulling its content from Netflix in 2019 to launch its own streaming service, the entertainment powerhouse has long been bolstering its intellectual property via acquisitions of Lucasfilm, Marvel Studios and Pixar. Hence its play for Fox.

But while Disney may be able to build an audience for its streaming service, few others can. To midsize and regional broadcasters, including renowned public service broadcasters such as the BBC, this headlong rush to consolidation of content and financial fire power represents an existential threat. BBC director general Lord Hall has already warned that British TV production is under serious pressure from the rise of Netflix, Amazon and Apple, and faces a £500-million shortfall.

Caught in a similar bind, commercial broadcasters are already teaming up to help weather the advertising storm. Such was the rationale behind the recent tie-up between the UK’s Channel 4, France’s TF1, Italy’s Mediaset and Germany’s ProSiebenSat.1.

Meanwhile, “cord-cutting’ will accelerate. In America, according to eMarketer, 22.2 million adults will have cut the cord of their cable, satellite or telco service by the end of last year, a rise of 33 per cent from 16.7 million in 2016.

Yet these unchartered territories will throw up opportunities too, particularly for niche, disruptive content creators. In the wake of VICE, BuzzFeed and Complex Media, young media entrepreneurs in OTT and video on demand can now reach, build and monetise large audiences directly.

Yet these unchartered territories will throw up opportunities too, particularly for niche, disruptive content creators. In the wake of VICE, BuzzFeed and Complex Media, young media entrepreneurs in OTT and video on demand can now reach, build and monetise large audiences directly.

The third driver is TV has been somewhat late to the party with data. That’s set to change. It’s well known that Netflix, while closely guarding its own data, uses it to drive personalised recommendations. Deploying data to hone commissioning, promotion and even, perhaps, the creative process itself is certain to be adopted across the industry.

A fourth trend is that we’ve entered the age of “peak TV”. A record 487 scripted shows aired in the US market last year, while producers have gone from selling to a handful of potential buyers to today’s proliferation of channels, streaming platforms and services.

As the battle for attention intensifies, telcos, corporates, tech giants and upstarts are all jockeying for position, resulting in an alphabet soup of distribution and business models. With viewers increasingly voting with their remotes, the industry’s Game of Thrones moment is far from over yet.