This summer Gemma Young pitched a business to investors. Among other things, DiversiTech Hub organises coding and speed mentoring events for children from low-income backgrounds, and funds workshops on diversity and inclusive fintech.

Ms Young had worked in IT banking for 17 years. She was tired of being seen by employers as a “ticking time bomb” about to ask for more maternity leave or flexible hours.

She thought that by getting to work with fintech startups early on, they could grow in a more inclusive manner and benefit future generations. But she has not yet secured funding.

“As a mum of four kids, people said to me, ‘You’re not investable. Don’t you want to be with your kids?’” says Ms Young. “Everyone likes to talk the talk, but in terms of what’s getting the next generation through, not much is going on, especially in terms of socio-economic diversity.”

Funding needed for inclusive fintech

Her experience is hardly unique. A study from the British Business Bank found that for every £1 awarded by venture capital firms, less than 1p goes to all-female teams.

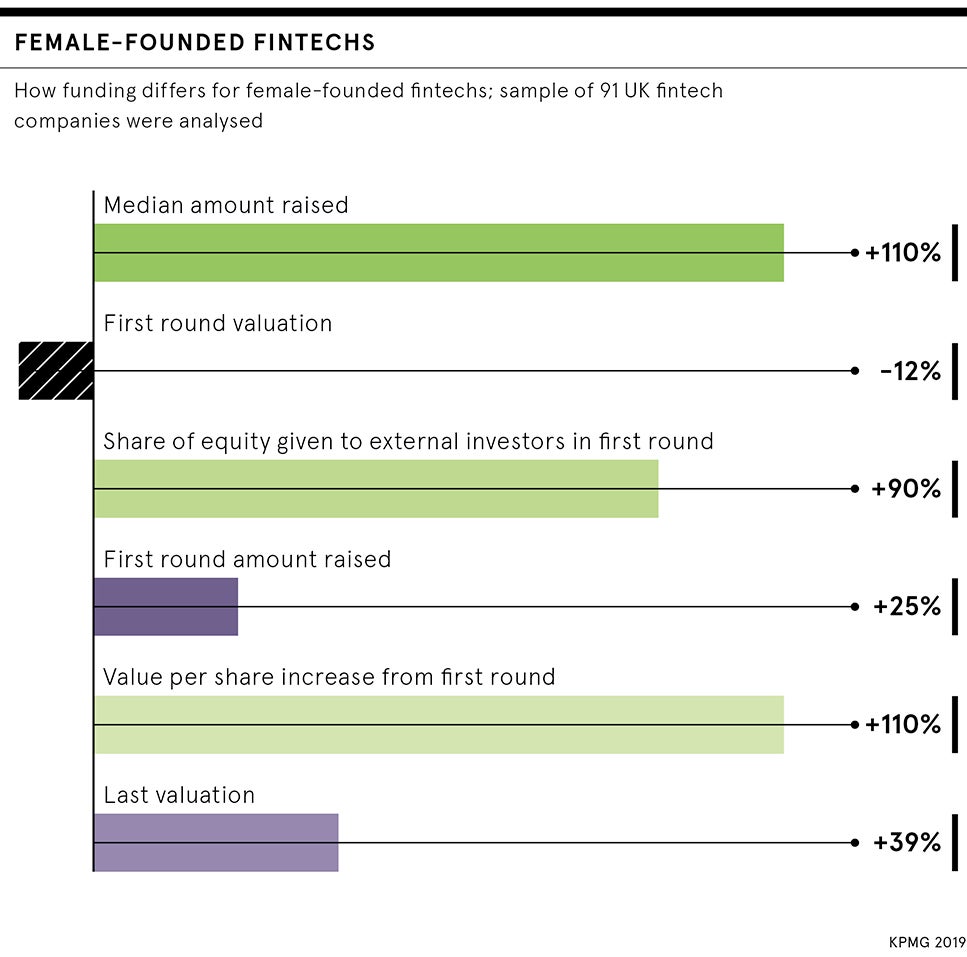

But in a world of so-called disruptive technology, Ms Young claims that fintech investors are not realising the potential of the biggest and most advantageous disrupter of all: diversity. They might be missing a trick, as research from KPMG shows that inclusive fintech companies with a female founder or co-founder typically deliver higher average returns of 133 per cent.

It is no surprise that this lack of investment in women fintech entrepreneurs leads to a lack of women in the sector overall. KPMG found that only 10 per cent of the 91 UK fintech companies in their study had a female founder or co-founder.

As a mum of four kids, people said to me, ‘You’re not investable. Don’t you want to be with your kids?’

Fintech route to success

One example of a male-founded fintech that has raised funding is tickr, an app that enables people to invest in companies in the business of climate, equality and disruptive tech.

Tom McGillicuddy, tickr’s co-founder, has raised more than £2.3 million since launching in 2018. He says his route to fundraising was “fairly typical”, working out of his flat, not earning money and instead attending hundreds of meetings, with 19 out of 20 ending in rejection.

“It wasn’t easy [to get funding], but what made it easier was our careers,” the 29-year-old says. Mr McGillicuddy is a chartered financial analyst, attended Oxford University’s Saïd Business School and worked for Wellington Management, while his co-founder Matt Latham has an MBA and worked for Barclays.

Part of the reason there is a lack of women is the recruitment process, says Clea Bourne, author of Trust, Power and Public Relations in Financial Markets, who claims fintech employers, just like traditional financial services, are focused on a select group of universities, degree courses and internships.

“It really is a scandal that financial services are not more egalitarian at universities and what about those who don’t go through the university route?” she says. “Diversity would have to take place in many different ways. It can’t just be an institution or industry saying let’s run a diversity campaign. The problem of bias is an institutional one.”

Work hours barrier to inclusion

There are two more barriers to promoting inclusive fintech. One is the long working hours. Fintech startups often need to work all hours to scale up their business quickly to deliver returns to investors.

“We’re hyper-aware of the lack of diversity. But unlike big organisations, we don’t have the time and resources to dedicate to it yet,” says Mr McGillicuddy, adding that venture capitalists are exclusively looking for exits of at least £1 billion.

Another barrier for women is the lower pay in startup culture, as Mr McGillidcuddy discovered when trying to hire more women.

“We’ve had to grow the team very quickly, predominantly with a team of [tech] engineers and we’ve only had two females apply for a job,” he says. “We offered it to one of them and she turned it down and went to a bigger, ‘safer’ job with a higher salary which we can’t compete with at the moment.”

War on female talent

Competition is rife, which could be a positive force. According to Innovate Finance, there are 1,600 fintechs in the UK and more people working in London in the sector than in New York or Silicon Valley.

“With that amount of growth, companies have to think not just about attracting talent, but retaining it too,” says Ms Young. “That war on talent is promoting diversity and inclusion.”

There are many examples of this, including more than 20 per cent of Monzo’s 700 staff identifying as LGBQA. In addition, Ms Young says there is a fintech trend of holding work events at lunchtime, instead of in the evening, allowing flexible and remote working, and increased paid parental leave. Online betting firm Smarkets even offers an emergency nanny service for employees with children.

But is this trend exclusive to fintech or is it part of a more general working culture? For example, the London Stock Exchange is considering shortening its market opening hours to promote work-life balance and diversity among its traders. And asset managers Baillie Gifford, founded in 1908, now offers 52 weeks’ paid parental leave to female and male employees.

Demonstrate the female power

Female chief executives in fintech help determine the workplace culture. One example is Anna Tsyupko, chief executive of Paybase, who tries to maintain a 50-50 gender split in the senior management team, which “trickles down into each department”.

“In our tech team especially, we’re proud that this strategy has attracted so many female engineers, a relative rarity in the tech space,” she says. “By championing diversity at every opportunity, our culture has been built on the basis of equal opportunity.”

An gender-equal, inclusive fintech firm can lead to long-term financial success, as evidenced by Croydon-based Automated Payment Transfer (APT). Kanchan Kamdar became chief executive in 2004, moved to a cloud-hosted solution in 2015 and now her firm oversees more than £40 billion worth of payments every year. Half her team has always been women. But interestingly, she’s never received any buy-out offers.

“When I first started working at APT, the previous owner was a single mum with one customer,” she says. “I got confidence by watching and learning from her, and then I took the risk and did a management buy-out. Thirteen years on, it was the best decision I ever made.”

Funding needed for inclusive fintech

Fintech route to success

Work hours barrier to inclusion