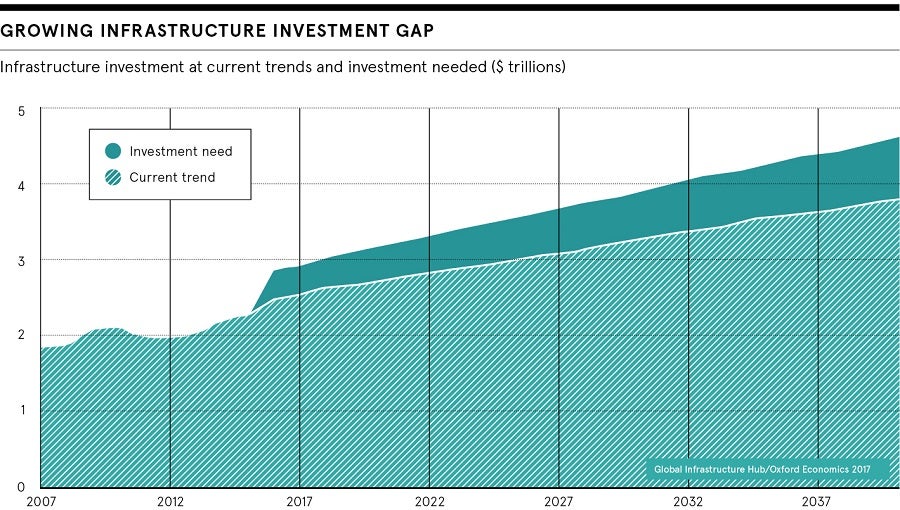

The world is facing a gargantuan $15-trillion infrastructure investment gap. According to Lawrence Slade, chief executive of the Global Infrastructure Investor Association (GIIA): “A huge amount of money is required around the world for infrastructure investment. It is one of those areas where governments cannot do it by themselves, so they absolutely need the assistance of private capital.”

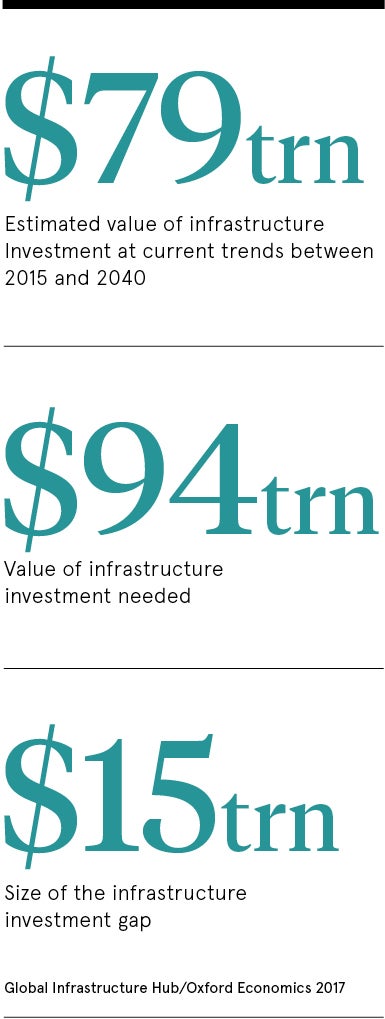

The $15 trillion number came from the Global Infrastructure Hub, an initiative of the Group of 20 countries (G20), last April. The organisation calculated the size of the gap by subtracting the $79 trillion that is likely to be invested globally in infrastructure projects between now and 2040 based on current trends, from the estimated $94 trillion of global infrastructure investment required.

The fact prevailing interest rates have remained ultra-low since the 2008 global financial crisis – in the United States they were slashed from 1.75 to 1.25 per cent in response to the coronavirus outbreak in early-March – coupled with bond yields at near historic lows, is boosting the attractiveness of so-called real assets.

Why invest in infrastructure?

And infrastructure’s ability to ride out economic downturns, by offering investors uncorrelated, stable and resilient returns at a time of geopolitical uncertainty, enhances its appeal.

Gershon Cohen, global head of infrastructure funds at Aberdeen Standard Investments, believes that even if bond yields were to rise, investors would not turn away from infrastructure. “If bond yields were to rise modestly, the overall cost of borrowing would rise, causing the borrowing costs of private-sector-funded infrastructure projects to also rise. This cost is generally passed on to the user, giving projects a higher return,” he says.

New and evolving technologies are presenting investors with many new areas to consider

According to financial data company Preqin, annualised returns from infrastructure investment, which includes investment in roads, railways, bridges, water supply, sewers, energy, fibre broadband and mobile networks, has averaged 8.9 per cent over the past ten years. That is ahead of the returns from global equities (7 per cent) and bonds (3.4 per cent) though lower than private equity (15 per cent).

Cohen says: “There’s little doubt that investing in infrastructure will give investors a better return than investing in bonds. The reason is that you’re taking on more risk. New and evolving technologies are presenting investors with many new areas to consider, so I see the infrastructure space continuing to offer lots of opportunities.”

Risks and opportunities of infrastructure investment

The biggest opportunities, especially in Europe and the 24 US states that remain committed to the Paris Agreement, are going to come from meeting net-zero-carbon targets. “The scale of investment that’s needed there is vast. If you throw in the digitalisation of our economies, including 5G and fibre broadband, technological changes could swamp individual economies’ ability to deliver, so they’re going to need all the help they can get,” says GIIA’s Slade.

“Overall, we see the prospects for the infrastructure sector as very positive. Obviously, there are uncertainties in the markets, a lot of which are political, but even in the UK this has settled down since the general election and in Europe you have a new European Commission which is starting to find its feet now.”

Another risk comes from investor naivety and irrational exuberance. When institutional investors, such as pension funds and life insurers, pile into the sector without knowledge or experience of infrastructure investing, they can lose their shirts.

“There are examples where projects that investors thought were safe, with monopoly positions and stable cashflows, turned out to be nothing of the sort,” says Cohen, citing some of the toll roads that were built in the United States in the 1990s and 2000s, for which the traffic projections turned out to be wildly optimistic.

The importance of looking long term

He also warns that, when too much capital chases too few assets in parts of the infrastructure investment market, bubbles can inflate and ultimately burst. “In the near term, it’s fairly frothy and competitive out there. People are, in some instances, paying 20 or 30 times EBITDA [earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation] for established assets, such as London City Airport. What investors need to avoid is buying or selling at the wrong point in the cycle. Ideally, to offset macroeconomic risk, they should hold infrastructure assets for long periods of time,” says Cohen.

What investors need to avoid is buying or selling at the wrong point in the cycle

Ensuring a healthy string of viable opportunities is going to be key to the future success of the infrastructure investment market. Slade concludes: “In terms of dry powder, there’s an awful lot of funding available. We just have to work to make sure the project pipeline is in place so realistic homes can be found for that.”

Why invest in infrastructure?

Risks and opportunities of infrastructure investment