Uber, the biggest taxi company in the world, does not own any taxis. Facebook, the biggest media company, does not create its own content. The biggest retailers, Amazon and Alibaba, don’t own any stores. The biggest accommodation company Airbnb has no hotels.

Tech companies succeed when they see the world differently and find new ways to meet genuine consumer demands at a fraction of the costs and with none of the complexity associated with the existing industry players.

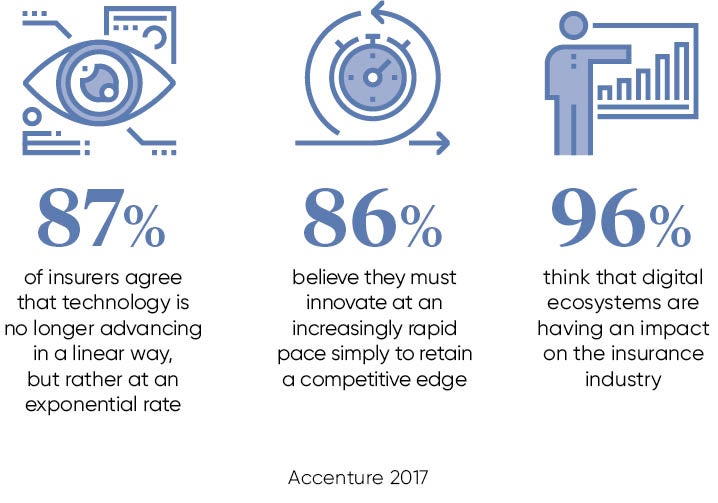

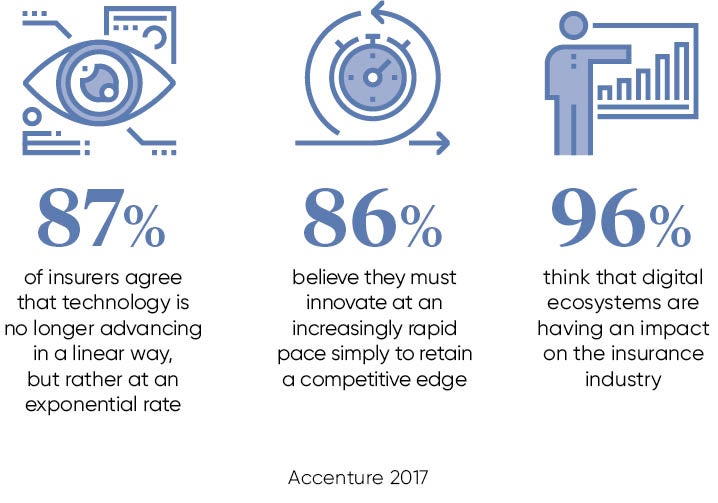

This is the allure of technology for the insurance industry. Characterised as it is, though to some degree unfairly, as old fashioned in attitudes, approach and customer service, it is seen both from inside and out as ripe for disruption.

The result in the past few years is that so much technology money had poured into the insurance sector that it has created its own buzzword – insurtech. All manner of innovations, business models and aps are being developed in the hope that they will revolutionise a traditional business.

But while there is money in abundance we still have not seen the vision and no one in the technology industry has yet come up with a fundamentally new way of thinking about the management of risk. What we see instead is the insurance industry trying to embrace technology and in many cases, in the larger firms such as Aviva, creating their own internal tech hubs to drive the process. We see much less of the technology industry thinking it can make money in insurance. There is as yet no sign of the insurance industry’s Amazon or Uber.

There is a good reason for this. Much of the effort currently is based on taking what has worked elsewhere in e-commerce and seeking to apply it to the insurance business. But there is a problem. Most of the consumer apps, which have achieved significant success in other areas, provide new and easier ways for people to find, buy and have delivered something they really want. These apps are pushing on an open door.

The problem with insurance is that nobody really wants it. People might understand they would be wise to buy it; they might even as drivers be compelled to have it, but that does not make it a purchase they enjoy. New technology can deliver insurance more cheaply, enable customers to shop around and make the process much faster, simpler and easier. But it cannot overcome this basic antagonism.

And it is the same with the issue of trust. The caricature of the industry is that when a claim is made, the insurer will try to chip away at the amount and the customer will chuck in a few extra items which were not lost or stolen in anticipation of this. Then there is a negotiation. Technology, in theory, should do away with this human interaction, but in a world where people struggle to come to terms with business “where the computer says no”, are they really ready for “computer says trust me”?

That is not to say there will be no benefits. Facial recognition technology already provides as much information on age, lifestyle smoking habits and health as a ten-page medical questionnaire, and without the ability to embellish the answers. Life policies could soon be sold on the basis of a selfie, without the need for the medical.

Insurance could become personal rather than product oriented. If you have three cars, all have to be insured, though you will only ever be driving one at any particular time. But technology will soon make it cheap enough to insure people rather than products, so the customer will be paying only when the product is in use, when actually driving or travelling, or taking on any of life’s other myriad risks.

However, it might not all be cosy for the customer. The other side of insurtech is the work being done on data, and the developing ability of underwriters to gather and process vastly greater quantities of information than ever before, in ways which give them far greater insight into where the risks really lie.

The upside is that these greater insights should lead to much keener pricing for the majority. The downside is that those whom the computer says are risky, might find it impossible to get any cover at all, just as flood insurance is hard to come by in some areas. This would also apply in areas of health, where gene sequencing might be used to predict future illnesses and longevity. If this leads to only the good risks being insured, it will provoke an intense debate around the issues of privacy and discrimination.

What all this underlines is that selling financial services is far more complex than selling conventional items in retail and insurance is one of the more complex areas within financial services. That complexity lends itself to bespoke operations and tailor-made policies whereas technology thrives on standardisation.

But these problems will eventually be solved and there is no shortage of money looking for the answers. Tällt Ventures, a Bristol-based research group which monitors these trends, estimate $1.69 billion was invested in insurtech in 2016 and that the number of deals done was 32 per cent up on the previous 12 months. The vast bulk of the money – 59 per cent – was invested in the US. However, the money backing UK startups also tripled from the year before though it accounted for just 5 per cent of the worldwide total – the same as China.

What is obvious is that all this money is already having a serious impact on how the industry thinks about itself. No one knows yet quite how the dice will fall, but they have no doubt that when the changes come, they will be fundamental.