Claire Smith, founder and chief executive of the animal cruelty-free investment platform Beyond Investing, is surrounded by other vegans. They include her chief investment officer, the head of ethical screening and the head of US marketing. Even her social media manager previously worked at vegan magazines.

“You have to walk the walk, not just talk the talk,” she says. “It’s rather galling to meet up with the heads of sustainability or impact at large banks, who are advising clients to put more into these areas, and my rejoinder is, ‘Have you looked at your own balance sheets?’”

In a global market of more than 3,000 “sustainable” funds to choose from, according to Morningstar, practising what you preach is an increasingly important factor for investors who want to place their capital with firms that align with their own values. But for all the genuinely ethical and admirable vision, Smith’s firm is small fry.

Big players dominate responsible arena

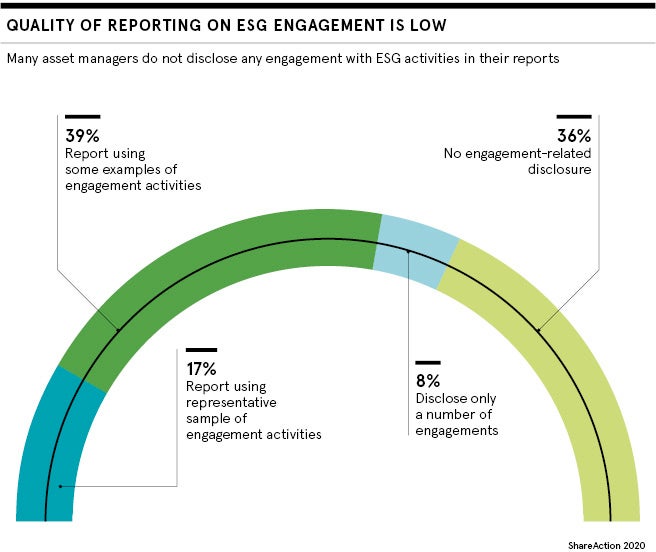

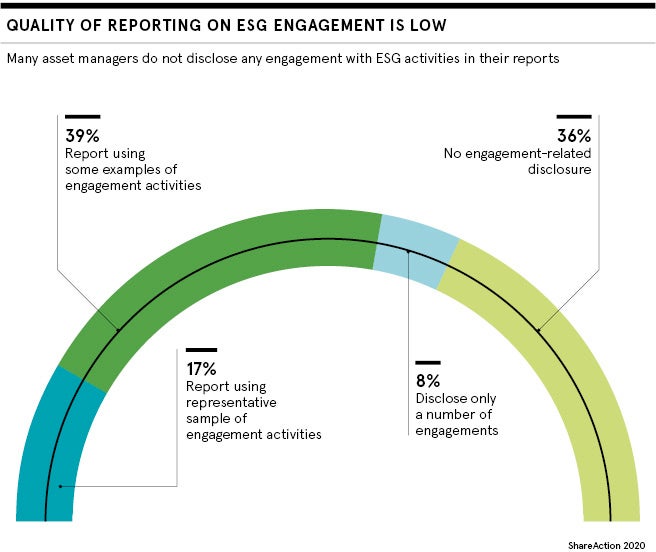

The majority of the world’s responsible assets are tied up with the world’s largest fund managers, who manage more money than the GDP of China, the United States and the European Union combined. And as a recent report from ShareAction found 89 per cent of the 75 largest fund providers offer some sort of responsible product range, but there is no significant correlation between asset managers’ overall responsible investment performance and the breadth of their environmental, social and governance (ESG) product suite.

“Our industry is driven by size,” explains Fabrizio Palmucci, founder and chair of the Asset Management Innovation Initiative, a Chartered Financial Analyst-accredited volunteer network.

“If you have a fund with a great and distinctive mission that resonates with clients, but only $55 million in assets, it’s very difficult to compete with bigger firms, so it’s down to the client to choose the strategies and firms that are both aligned with the client values. Clients shouldn’t be scared to invest in smaller firms.”

Larger firms trying to be responsible

That is not to say the big firms are not trying. They are, generally speaking, increasing the number of staff in their stewardship teams, as well as upping the number of corporate engagements and proxy votes at AGMs at the firms they invest in.

They are also very good at telling other companies what to do. Larry Fink, chief executive of BlackRock, the largest asset manager in the world, said in his latest annual letter that companies should be more open about, for example, the diversity of their workforce, how they handle data and the sustainability of their supply chain, and to look for purpose rather than short-term return.

“As I have written in past letters, a company cannot achieve long-term profits without embracing purpose and considering the needs of a broad range of stakeholders,” he wrote.

Gender gap still prevalent in investment sector

Diversity and inclusion is still a massive challenge within fund management. A 2019 report from PwC and the Diversity Project found that due to a worrying trend labelled “diversity fatigue”, the average mean pay gap within the fund management sector is 31 per cent, an increase of 0.8 per cent in the two years since mandatory pay gap reporting was introduced in the UK for firms with more than 250 employees.

Some firms go above and beyond with transparency. One example is Federated Hermes’ Responsibility Report 2020, which outlines, among other things, the chief executive to median employee pay ratio, gender diversity of its workforce, how many hours its employees spent volunteering, and its waste and paper usage.

“What we encourage others to do, we are working on ourselves,” says Leon Kamhi, Hermes’ head of responsibility, whose team includes 55 people and five specialist ESG advisers. “Three to four years ago, we wanted our annual report to be about more than financials, so now it includes what we’re doing for all our stakeholders, not just our investors and shareholders, who are very important too.”

Kamhi concedes the firm is not yet where it wants to be on gender pay, reporting a median hourly wage and bonus gender gap of 27 per cent and 68 per cent respectively, but he remains positive about transparency being the first step to change. “Sunlight is a great disinfectant,” he says.

Regulation forces firms in responsible direction

Transparency is also becoming law, with the European Commission’s Green Taxonomy requiring investment houses to disclose how they integrate ESG in their processes by 2021.

But can an investor expect an investment firm, even one that puts ESG at the centre of its ethos, to get everything right? Patricia Hamzahee, founder of Integriti Capital, says it is more honest for a firm to take a strong view and be consistent with it.

“If you’re just bowing your head to a range of ESG issues because it looks important, you won’t make much impact, even if your intentions are right,” she says. “It’s far better to be very intentional about things that really matter to your firm and your clients. You decide that this is where we can make a difference and other people can do the heavy lifting elsewhere.”

If you’re just bowing your head to a range of ESG issues because it looks important, you won’t make much impact

ShareAction notes that more than half of sustainable funds are centred around low carbon, what Hamzahee describes as “low-hanging fruit” and far fewer options that explore alternative themes such as biodiversity.

Investors must be responsible for their choices

As a result, investors will need to decide what matters to them too and look for it. Beyond Investing provides an exchange-traded fund that is centred around animal exploitation. Research from Veris Wealth Partners shows there is now around $3.4 billion invested in funds that look through the lens of gender equality. While Impact X is a venture capital firm focusing on investing in diverse business owners, particularly Black-owned businesses, a topic that has reached new levels of prominence since the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

Kamhi insists that the whole investment management sector is moving in the same direction. “In terms of acting as a responsible firm and having an appropriate inclusion and environmental policy, this is a challenge for every firm in the world, whether it’s so-called ESG driven or mainstream driven,” he concludes.

“There is a case that the principles of responsible investment will become the principles of investment. If you don’t include a material environment, social or governance factor in your evaluation, you’re in dereliction of your financial fiduciary duty, in my view. It’s as simple as that.”

Big players dominate responsible arena

Larger firms trying to be responsible

Gender gap still prevalent in investment sector