There are few things that seem to unnerve currency traders more than immense, unexpected volatility in the $5.1-trillion-a-day foreign exchange market. One of them, though, might be no volatility at all.

Over the last few months, volatility in global currency markets has hovered around its lowest level in the past five years. Activity has been muted by central banks acting in tandem, economic data that’s mixed at best, a wait-and-see approach in relation to Brexit and fractious US-China trade relations.

All of this has made it tricky for traders, asset managers and hedge funds to find compelling reasons to bet on or against any single currency.

Everyone’s heard of the quiet before the storm; the only question now is when will that storm hit?

“It’s feels a bit like we’re hanging around on the sidelines,” says one London-based trader, who asked not to be named. “It’s hard to show you have a good idea when there’s really very little happening to which you could respond.”

In April, HSBC strategists wrote in a monthly client note that they had made the unprecedented decision of not introducing any new currency trade ideas for the month ahead, partly because little had changed in the preceding quarter.

According to Daragh Maher, the bank’s US head of currency strategy, the trades they had entered in January, February and March had neither hit their take-profit level nor their stop-loss point at which a security is sold to limit loss.

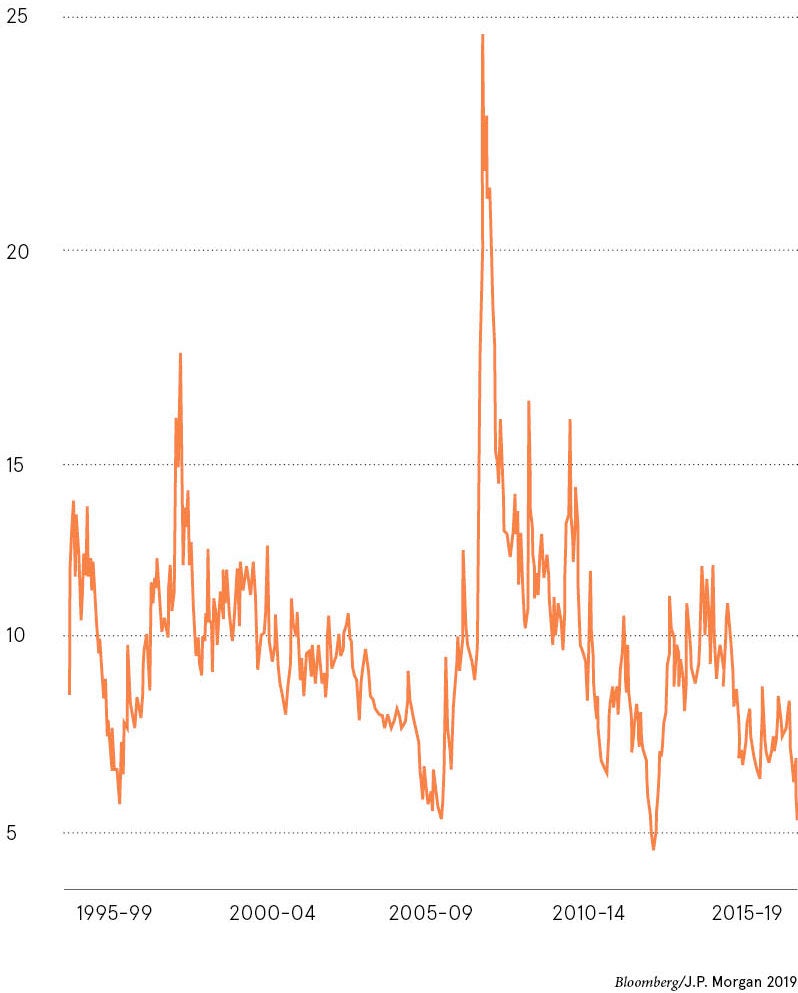

Implied three-month volatility for currencies of the G7 economies was recently around two standard deviations below its long-run average, according to a J.P. Morgan index frequently cited by market players.

Interest rates remain lower for longer

Current unfluctuating foreign exchange markets are to a large extent the result of monetary policy. Major central banks in America, Europe and Japan announced long-term stimulus measures to support their respective economies in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

That dramatically subdued volatility until the US Federal Reserve became the first to raise interest rates in December 2015. Policy moves since then have been cautious though, and fresh economic slowdowns across Europe and America have recently prompted dovish tones on both sides of the Atlantic.

In mid-June, the Fed signalled it might cut interest rates by as much as half a percentage point over the rest of 2019, responding to increased economic uncertainty and a drop in expected inflation.

A Reuters poll recently showed that a majority of economists expect by the end of September the European Central Bank (ECB) will have either cut its deposit rate or eased its forward guidance further by pledging to keep interest rates lower for longer.

“In essence, the promise of cheap money from central banks for longer appears to have calmed nerves,” says Jane Foley, senior currency strategist at Rabobank.

Many agree and argue that an imminent resurgence in volatility is unlikely, both because of central banks, but also due to a chronic lack of clarity on Brexit.

“Even though the EU financial system is stronger and [youth] unemployment continues to grind lower, the strong impulses, including growth and inflation, are just not present and as such the system remains choked,” says Gregory Perdon, co-chief investment officer of private bank Arbuthnot Latham.

Commenting on the Fed’s decision in June to hold interest rates steady, he says the US central bank was “nursing the market, not shocking it”.

On Brexit, Mr Perdon says the pound “is and will continue to trade in no-man’s land” reinforcing low volatility.

Is the end in sight?

Nonetheless, there are reasons why gyrations could return. Strategists at MUFG Bank say that if the Fed were to suddenly turn more hawkish as a result of stronger than anticipated economic data, or if the Chinese economy were to slow down, that might be enough to jolt markets out of their prolonged slumber. Others say that a sudden and dramatic escalation of trade tensions between the United States and China could achieve the same result.

Didier Saint-Georges, managing director at Paris-based investment firm Carmignac, which has around €39 billion (£35 billion) of assets under management, also notes there are “several good reasons to expect a rise in [foreign exchange] volatility in the coming months”.

“First, as central bank action has failed to put global economic growth back on a strong footing, more unconventional action may be considered again soon,” he explains. “For instance, in Europe, inflation expectations are extremely low, so that the ECB might have to revert back to quantitative easing soon, before these expectations get anchored dangerously low. This could potentially weaken the euro.”

Likewise, he says, the Fed could take an even more dovish turn by both announcing a fresh round of quantitative easing and cutting rates again. “Indeed, in a slowing world, with rising protectionist threats and poor domestic demand, the cost of having too strong a currency can be very painful,” Mr Saint-Georges notes.

Will Brexit increase FX volatility ?

In the UK, some say that Brexit, one of the primary roots of low volatility, also has the potential to turn the situation around.

In late-May, a gauge of the difference between expected swings in the pound over the next three and six months rose to its highest level in more than three years, according to Reuters. That’s likely to indicate a rising sense of anxiety linked to the October 31 Brexit deadline.

According to Jordan Rochester, currency strategist at Nomura, it’s now looking increasingly likely that Boris Johnson will be the UK’s next prime minister. Mr Johnson’s pledge to leave the EU on October 31, whether a deal has been struck or not, is a “problem”, Mr Rochester notes.

“Any increase in hard Brexit pricing as the October deadline approaches will likely drive [the pound] lower and implied volatility higher,” he adds.

A second London-based trader, who declined to be named, says the market is for now undeniably dominated by a mood of wait and see.

“As we’ve learnt from the past few years, though, just when you think you’ve got things figured out, everything suddenly changes,” he says. “Everyone’s heard of the quiet before the storm; the only question now is when will that storm hit?”

FX volatility at a multi-year low

The J.P. Morgan Global FX Volatility Index, which tracks options on currencies of major and developing nations, is a benchmark for implied volatility.