As the UK approaches Brexit, financial experts warn that a significant consequence of its departure from the European Union could be that money laundering is harder to combat.

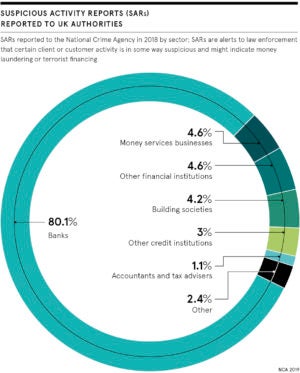

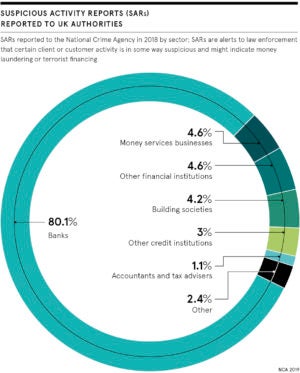

According to Transparency International, billions in illicit cash flow through the UK economy every year; money which is laundered by purchasing property and businesses. The corrupt wealth, often stolen public funds and bribes, is legitimised after passing through UK financial institutions. The National Crime Agency (NCA) has estimated that “many hundreds of billions of pounds” are laundered through UK banks and their subsidiaries annually.

Corruption Watch estimates that UK banks have been implicated in the laundering of at least £5.6 billion of corrupt money since 2008. It is likely that the real figure is far higher; in 2015, Deutsche Bank found strong evidence that the UK had received £70 billion in illicit funds between 2006 and 2015, with a significant amount originating in Russia.

Brexit raises questions over whether UK will stay in Europol

The UK is currently a member of Europol, the EU law enforcement agency, which is mandated to tackle organised crime, including money laundering, within the bloc. Europol maintains a criminal information and intelligence register called the Europol Information System (EIS), which gathers the national crime databases of all member states and is searchable by law enforcement agencies across the EU.

After March 29, or when the UK leaves the EU, it is unlikely to continue to be a member of Europol, which would restrict its access to the EIS unless new bilateral agreements are reached with each of the member states. Lawyers and accountants believe this could hinder the ability of UK officials to combat the flow of illegal money since the UK government would find it harder to track the movement of funds.

Last year, the NCA said UK-based companies seeking to increase trade with countries outside the EU would be more likely to come into contact with corrupt markets, especially in developing countries. The agency also warned that Brexit would provide added incentives for criminals to launder money by investing in UK businesses. Other agencies that contributed to the assessment included police forces, MI5, MI6, GCHQ, the Border Force, Immigration Enforcement and the Prison Service.

Post-Brexit, anti-money laundering measures may disappear

The NCA also said criminals would look to take advantage of any redesigned customs agreements set up after Brexit, as well as gaps in intelligence-sharing between countries.

“There are a lot of concerns, looking broadly at money laundering and criminal justice co-operation; all these measures within the EU are a big area of concern,” says John Binns, partner at BCL Solicitors in London, specialising in business crime and money laundering.

“Extradition, the sharing of information, the mutual recognition of asset-leaving measures, all of that gets turned off on Brexit day. In advance of that, it all needs new security measures fairly swiftly ironed out. In areas of anti-money laundering, there need to be agreements about how the UK will be treated post-Brexit by the EU. Adequate data protection rules would also need to be in place. No post-Brexit scenario currently exists.”

Recent years have seen the EU tighten its laws in the fight against financial crime with the adoption of new legislation like the 5th Money-Laundering Directive, which establishes a centralised public register of companies and ultimate beneficiary owners. This law brings transparency to business practices and attempts to place limits on illicit behaviour by reducing the number of shell companies.

The UK last year unveiled new draft laws which would force the offshore owners of UK property to reveal their identities or face jail sentences and unlimited fines. Overseas companies owning UK properties will be required to reveal their owners on a publicly available register. Separately, a cross-party campaign group of MPs also tabled an amendment to the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill 2018 requiring the governments of 14 British Overseas Territories to impose public registers. Registers were due to be introduced by the end of 2020; the deadline has been extended to 2023.

As bank HQs leave the UK, so too may anti-money laundering experts

“I think if Britain were to leave Europol, which is a likely possibility, the UK would lose access to intelligence-sharing through the EIS and the Schengen Information System. I think that would compound a number of problems around Brexit,” says Dev Odedra, an anti-money laundering expert, who has worked with a number of leading UK retail and investment banks.

Mr Odedra says a lack of access to the EIS would impact the work of the NCA. “Broadly speaking, if the NCA were to issue notices and warnings, they would have less intelligence they could action. This is because they would be cut off from the EU’s databases and anything coming down wouldn’t be up to date. When it comes to anti-money laundering initiatives, access to EU registers is important if you want to tackle the problem,” he says.

Another related issue is the fear that as banks move their headquarters from the UK, Brexit could encourage anti-money laundering experts to depart. “Talented people are leaving the UK out of fear,” says Mr Odedra. “We may lose people with anti-money laundering skills who could go to Germany or France. We are beginning to see this as banks are deciding to move operations out of the UK to be closer to a larger market.”

Much like the trade in counterfeit goods, money laundering flourishes in areas of legislative weakness. If the UK is serious about its post-Brexit ambitions, it should promptly enter into new intelligence-sharing agreements with its future trade partners.

Brexit raises questions over whether UK will stay in Europol