Digital-only banks, known as neobanks, have risen fast thanks to innovative low-cost services that chime with millennial consumers. But overall the coronavirus pandemic has not been kind to them.

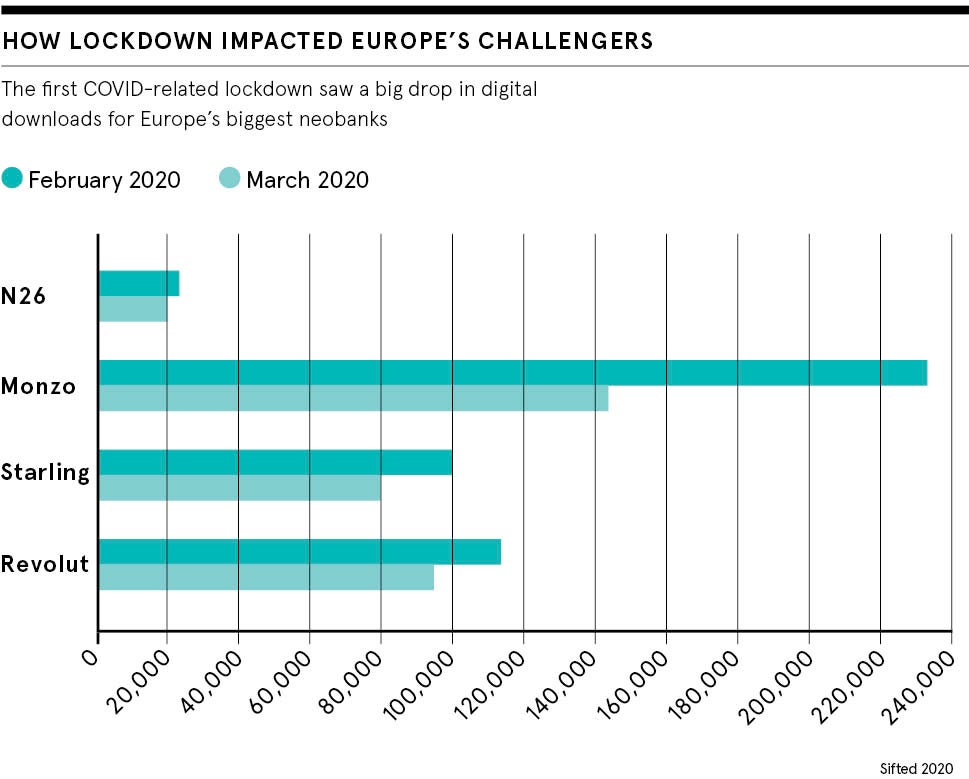

Data from Curve, a service that brings multiple bank cards together into one, shows people’s use of challenger banks and neobanks dropped by 90 per cent at the start of the first UK lockdown in March, compared to a 60 per cent drop-off for traditional banks.

And both Monzo and Revolut, two of the biggest players, have had to cut hundreds of jobs after revenue fell, with Monzo even saying in July that the pandemic threatened its ability to operate.

Now another, potentially devastating, threat has emerged. With the UK economy on track to suffer its sharpest contraction in 300 years, the Bank of England has hinted that it might consider taking interest rates below zero for the first time, as has been done in the eurozone and Japan.

It would penalise the hoarding of cash to stimulate growth and effectively force banks, which usually set their own rates against the benchmark, to charge customers for current accounts, putting neobanks’ no-frills model under real pressure.

Why are neobanks struggling?

“Neobanks have a much leaner cost structure than traditional banks so they can live with relatively small margins, but if rates go below zero, they will struggle,” says Thorsten Beck, professor of banking and finance at Cass Business School in London. “The question is, can you continue to offer that innovation and convenience if you are facing these costs?”

The issue is that most neobanks have only recently started lending money, which is typically how banks make most of their revenue. Instead, they rely heavily on deposits, overdrafts and ancillary services, such as low-cost foreign exchange transactions, which don’t make much profit, and even those income streams are under threat.

“International travel has fallen away in the crisis, along with that income, and zero or negative interest rates would make it very hard to make money on transaction accounts,” says Beck.

Neobanks have already begun to tighten their belts because of the pandemic. In November, another market leader, Starling Bank, became the first UK bank to introduce negative interest rates for personal accounts, although only for a small number of its customers who hold high balances in euros.

Customers pay -0.5 per cent on balances over €50,000, a cost Starling says it is passing on to reflect European Central Bank rates.

Separately, Monzo has begun charging customers a 3 per cent fee if they withdraw more than £250 a month from cash machines, unless they use Monzo as their main current account.

What will happen if interest rates plummet?

Jaidev Janardana, chief executive of peer-to-peer digital bank Zopa, thinks more banks will raise costs if rates turn negative. The issue for him is that they typically hold money they are not lending out with the Bank of England in a reserve account, or in bonds or gilts, where interest is tied to the base rate. And this money would become a cost instead of a source of revenues.

“These potential costs will need to be offset, either by charging the customer for the current account, a practice which UK consumers are not used to, or by increasing the number or margin of other products that banks can monetise, such as loans,” he says.

Of course, the margin on credit is also likely to fall if rates turn negative, but banks with low loan-to-deposit ratios are better placed to weather the storm.

Janardana says Zopa would be “largely immune” because it makes 90 per cent of its money from lending and credit cards, with rates based on the wider market and individuals’ creditworthiness rather than the benchmark.

Starling, which only started lending last year, had already built a chunky loanbook of £1.3 billion by September 30, which compares to total deposits of £3.7 billion and 1.7 million customers. The firm, which also became the first neobank to move into profit in November, says it is “very well placed to handle negative interest”.

Monzo, however, may have a tougher time. It had gross lending of £143.9 million in the year to February 2020 versus deposits of £1.4 billion, while losses at the bank doubled to £113.8 million. Monzo did not respond to a request for comment.

Raising fees risks losing customers

The longer-term risk of negative rates is that it could undermine neobanks’ value proposition of affordability and convenience, which has made them such a hit with 18 to 34 year olds. It would also come at a time when traditional banks are catching up in terms of innovation.

“The pace of innovation of the neobanks has outstripped the established banks who are now making efforts to close the gap and reduce the erosion of differentiation as they introduce more features for their customers,” says Terry Farnfield, partner at analysts BearingPoint.

“For neobanks to maintain their edge, they must double down on their customer-centricity and keep leveraging their agility to stay more aligned with customer needs and expectations.”

Around one in ten people in the UK now have a neobank account, but only around half of them consider it to be their main bank account, with most continuing to rely on big players. Such existing market challenges, coupled with the impact of COVID-19, could mean some challengers go under or get snapped up by bigger rivals, says Beck.

However, while uncomfortable changes lie ahead, no one believes COVID will kill off the neobank phenomenon.

The question is can you continue to offer that innovation and convenience if you are facing these costs?

Matt Baxby, chief executive of Revolut Australia, says his firm is “cautiously optimistic” about the future, even though recovery from the pandemic will not be instant. “The economic impact of COVID has meant most companies are re-examining their business models to some extent, to ensure they are still effective,” he says.

Starling Bank says the pandemic is in fact accelerating the shift to digital banking, with its own customer base having grown since March.

According to the bank: “One of the advantages of being a digital bank is that we have a much lower low-cost base than the legacy banks. We can achieve as much, and more, with our engineers as the big banks can with teams many times the size of ours. And as a branchless bank, we do not have to service the costs of branches.”

Digital-only banks, known as neobanks, have risen fast thanks to innovative low-cost services that chime with millennial consumers. But overall the coronavirus pandemic has not been kind to them.

Data from Curve, a service that brings multiple bank cards together into one, shows people’s use of challenger banks and neobanks dropped by 90 per cent at the start of the first UK lockdown in March, compared to a 60 per cent drop-off for traditional banks.

And both Monzo and Revolut, two of the biggest players, have had to cut hundreds of jobs after revenue fell, with Monzo even saying in July that the pandemic threatened its ability to operate.