The UK’s open banking revolution got off to a somewhat slow and shaky start. Consumers remain largely in the dark, and the bulk of those who are aware of what’s on offer are mistrustful and fearful about potential abuse of their data.

Only four of the nine banks that the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) mandated to participate in the insurgency had their technological ducks in a row in time for the January 13 deadline. One of these seemed to be on a mission to sabotage the entire programme through the media.

And by the time the CMA’s “managed rollout” ended on April 17, only 18 third-party providers, many of which are fintech companies, had received the Financial Conduct Authority’s stamp of approval to plug themselves into the banking system and start playing in the open banking space.

January 13 was D-Day for open banking, the date by which the CMA was obliging nine of the UK’s largest banks to be in a position to start sharing their customers’ data, subject to customer approval, with third-party providers approved by the Financial Conduct Authority through standardised application programming interfaces (APIs).

However, Bank of Ireland, Barclays, HSBC, RBS and Santander were not ready on time. They have since jumped through the regulatory hoops to start operating in the open banking market, though Spain’s Santander does seem to be the biggest foot-dragger and has been granted an extra year to provide 40,000 customers of its private banking arm Cater Allen everything that open banking will offer.

The near-term goals of open banking are to create a seamless, but secure, inter-operability between banks and authorised non-banks, so customers’ transaction data can be released “out into the wild”, as Rowland Manthorpe at WIRED puts it, “in the hope that startups will turn it into innovative products and even new types of bank”.

The near-term goals of open banking are to create a seamless, but secure, inter-operability between banks and authorised non-banks, so customers’ transaction data can be released

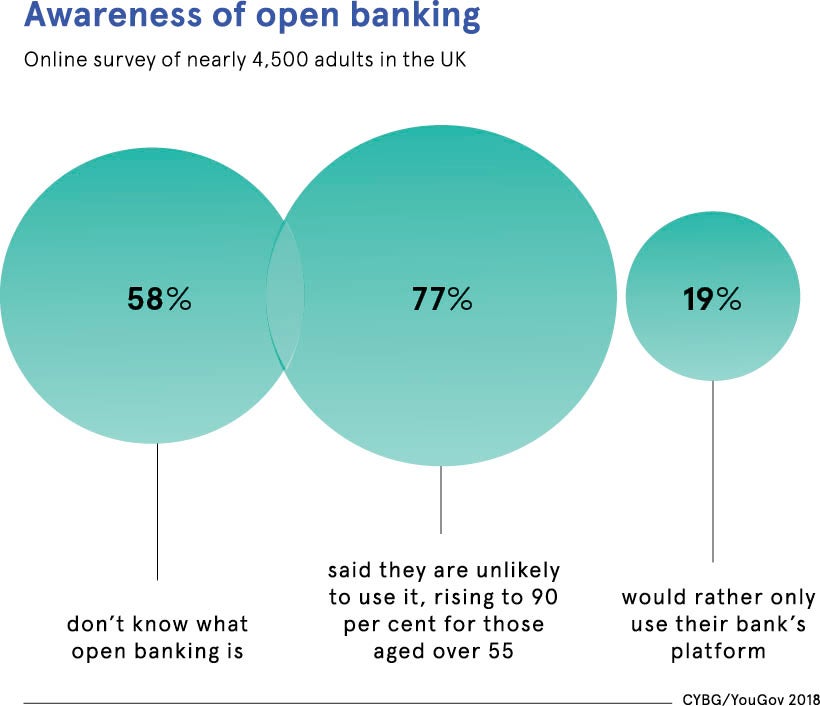

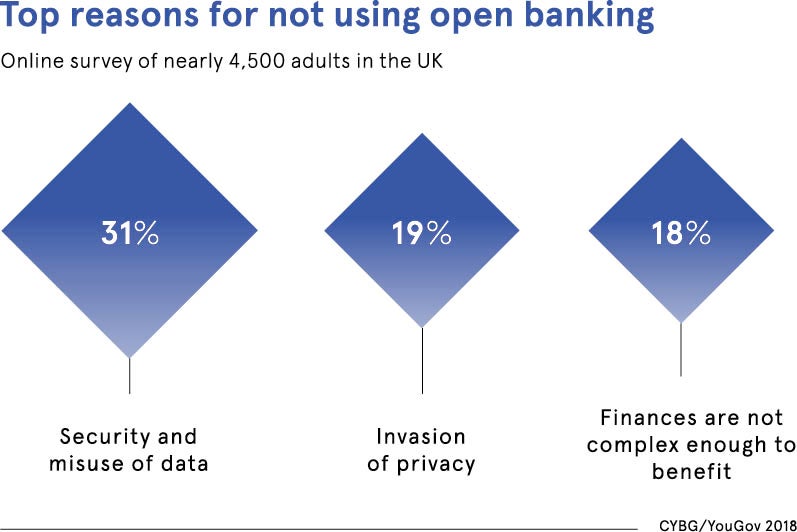

Even its evangelists now acknowledge that reaching this brave new world will take time. Among the biggest obstacles is lack of enthusiasm from the UK public. A host of surveys released in the run up to January 13, and since, suggest that most UK consumers remain blissfully unaware of open banking, dubious of what’s in it for them and tend to regard the sharing of their personal transaction histories as anathema.

Bob Graham, head of banking and financial services at Virtusa, says: “Consumer awareness is still relatively low and the industry hasn’t yet enough in terms of education or coming out with products and services which have grabbed people’s attention.”

It did not help matters when RBS, through its NatWest arm, highlighted cybersecurity risks on the eve of launch day. The majority state-owned bank warned that open banking, which is essentially a gold-plating of the European Union’s Second Payment Services Directive (PSD2), might enable hackers to “fraudulently access customers’ money”. This largely spurious assertion went down particularly badly at Open Banking Ltd, the body that has been charged with overseeing the rise of open banking. Imran Gulamhuseinwala, Open Banking’s boss, describes NatWest’s intervention as “an unhelpful bit of noise”.

Then the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal erupted on March 20. That further heightened public concern about entrusting personal data to the barons of cyberspace, as well as a growing recognition that “if the service is free, you are the product”.

However, Flux chief technology officer (CTO) Tom Reay defends open banking saying the ways in which customers’ data will be shared has been massively misunderstood. “It’s a lot safer than the screen-scraping, which is what we had before,” he says. “That is fundamentally unsafe, as it involves providing your login data [username and password].”

Mr Gulamhuseinwala, who is on secondment from EY, elaborates: “From the outset, we wanted to create open banking as something that puts the consumer in control of their data. To achieve that, we’ve built consent right into the architecture of the system.

“Consent has to be explicitly given; it needs to be given for very clear and stated purposes, and if the customer wants to revoke that consent, they should be able to do that just as easily as they gave that consent. That is a fundamentally different approach to some of the large tech companies and was designed with GDPR [EU General Data Protection Regulation] in mind.”

However, Ewen Fleming, financial services partner at Grant Thornton, has more sympathy for the way most consumers have so far greeted this financial revolution with a massive shrug of the shoulders. “The additional benefits consumers are going to get in exchange for sharing their financial data remain unquantified and elusive,” he says. “Many in the industry have decided this is the right thing to do, without really weighing up what consumers want and need. I personally think there has been a lot of hot air, and the air just got hotter with the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal.”

Mr Fleming says it doesn’t help that some banks remain ambivalent about entering open banking. “None of the banks see open banking as a big opportunity,” he says. “For the most part, they’re doing the bare minimum to ensure they’re ready, exactly as they’d do for any other regulatory change.”

But other commentators warn that if banks want to avoid becoming “dumb pipes” and losing control of their relationships with customers, they are going to have to become much more proactive. Some, including HSBC, are already working hard to develop new offerings, such as account aggregators, which pull in data from other sources approved by customers under the open banking banner.

Danny Healy, API professional in the office of the CTO at MuleSoft, says: “The banks are all trying to understand what the killer app might be. They’d like a crystal ball, but life isn’t that straightforward.”

Mr Reay at Flux, which has already been “paired” on a serial basis with all nine participating banks since January 13, is more bullish about the banks’ attitude, saying: “All the banks were genuinely enthusiastic and wanting to get things working. They’re all embracing the opportunity of it.”

Caroline Plumb, founder and chief executive of cash-flow management fintech Fluidly, believes if open banking does turn out to be a damp squib, it won’t be because of lack of consumer trust. “It will be the result of a failure to deliver the functionality that consumers and businesses are looking for, as well as a fragmentation of standards across markets globally,” she concludes.