Open banking is about to shake up the industry. From January 13, high street banks were obliged by law to share consumer data with third-party providers, so long as consumers consent. Open banking will allow consumers to access a galaxy of new services, including account aggregators, so they can keep track of accounts across multiple banks and services, and direct payment services, to disrupt the traditional payment system.

But there is a problem. Privacy is a huge concern. If consumers don’t trust banks to keep their data safe, they will avoid engaging altogether. But how corrosive are privacy worries?

A new survey by the Emerging Payments Association, an industry body for the payments industry, shows 34 per cent would not wish regulated authorities to access their accounts to offer better banking and services. But 35 per cent would consent to the data being used, as long as it remained secure. Awareness of open banking is poor with 51 per cent unaware of the term.

So clearly privacy is a major challenge. But if this gulf in trust can’t be breached, the efforts will be severely underused.

What’s the solution? The first step is to highlight that the open banking protocols are genuinely secure. Raconteur asked more than 20 banks, third-party service providers and security consultancies for their verdict on security, and received an overwhelmingly confident response.

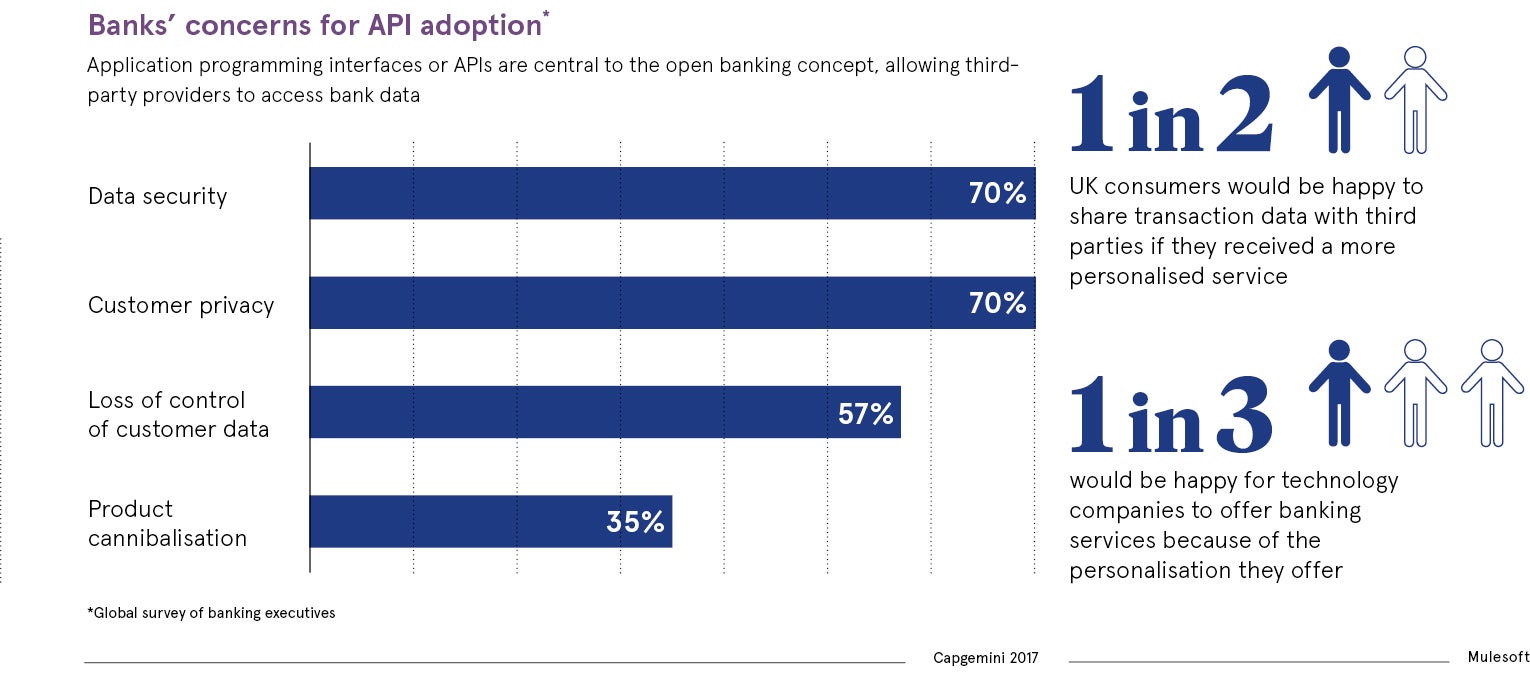

Henry Felton, senior consultant at Capgemini Consulting, says: “The type of technology being used, APIs [application programming interfaces], has been specifically chosen with security in mind and those who want to get access to customers’ bank information must be authorised by the regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority.”

There are a few doubters. Tim Ayling, Europe, Middle East and Africa director of fraud intelligence at RSA Security, says it’s foolish to write off consumer concerns as merely irrational. “An easy way to access customer banking data will always be at the top of the hacker wish list,” he says.

“While there are undoubted benefits to open banking, the aggregation of customer data held in potentially less-secure and dynamic environments, such as fintech startups, is a hacker’s birthday and Christmas come together. The risk to the consumer is very real.”

Critically, he adds: “Whether this undermines open banking is a whole new question however. Many consumers seem happy to live the risky way. We only need to look at the amount of personal information shared on social media to understand that.”

This is the crux of the debate. Security is always a trade-off. Service providers must dangle tantalising products in front of consumers to change behaviour. If so, the worries about privacy and security, real or imagined, will fade.

If the industry fails to win consumers’ trust, this revolution in banking will fail before it has even begun

It’s early days, but signs are encouraging. When shown benefits, consumers are far more likely to agree to share their data. A UK survey by MuleSoft revealed 48 per cent would be happy to share transaction data with third parties if they received a more personalised service. One in three would be happy for tech giants, such as Google, Apple and Facebook, to offer banking services because of the personalisation they offer. Ask younger consumers and the figure rises to half.

Some open banking participants are on their way to becoming household names. Revolut and TransferWise offer cut-price foreign exchange services. There are new banking entrants, or challengers, such as Monese, Atom, Monzo, Coconut and Starling. The process of taking open banking mainstream is well underway.

The mission depends on no false steps. Alas, there is a minor, if limited, problem with current open banking practices. Megan Caywood, the chief platform officer of Starling Bank, the app-only challenger, waggles her finger at slackers in the banking industry that may be using a sub-standard protocol.

“Many banks did not meet the January 13 deadline, so are instead enabling screen-scraping as an interim solution to APIs. For those unfamiliar, screen-scraping requires users to share their banking credentials – logon and password – to share their data with a third party, whereas APIs do not, and this method is an insufficient and insecure way of sharing data.

“It’s possible that allowing this as an interim solution to buy the banks more time to properly implement open banking will accidentally undermine the intent of the legislation and decrease customer trust.” Starling Bank, like other top-tier providers, only uses maximum security APIs to avoid the screen-scraping problem.

Poor practices like screen-scraping could lead to a leak of data and a scandal. If errors happen, consumers need the right of redress. Simon Paris, deputy chief executive at fintech services provider Finastra, says: “Creating the appropriate safeguards and redress mechanisms is a critical part of gaining consumer confidence, so they know who to turn to if something happens.

“If something goes wrong with a payment, the bank should help customers get a refund. If someone misuses a customer’s data, then the case is subject to data protection laws and complaints should be directed to the Information Commissioner’s Office.”

Ultimately, no one should believe the adoption of open banking in scale is guaranteed. Carlos Abarca, TSB’s chief information officer, warns: “The industry must give customers the confidence that their money is safe. In this emerging phase of open banking, tactical solutions, such as web aggregation, are being adopted that could pose a security risk.

“If we fail to communicate the security benefits of new technologies, we risk undermining open banking completely. Ultimately, if the industry fails to win consumers’ trust, this revolution in banking will fail before it has even begun.”