Imagine you’re on your way back from work and you pop into a shop. You weren’t looking for anything in particular, but an hour later you find yourself walking out with a big smile and multiple bags in tow. What happened? Behavioural economists call it the effect of “shopping momentum”.

We like to think we’re rational consumers when it comes to our spending. After all, our financial decisions have a huge impact on our wellbeing. Think of an unforgettable holiday or a house bought at the wrong time. But in reality, we’re emotional creatures, susceptible to biases and external factors.

Luckily, behavioural economics makes our irrationality more predictable. In the words of Nobel prize-winning economist Professor Richard Thaler, it’s “economics done with strong injections of good psychology”.

Shopping momentum and framing techniques

When considering paying for goods, researchers have found that buying one thing makes us much more likely to buy subsequent items, regardless of our previous deliberations. Browsing things to buy online or in a store, puts us in a mindset of “deliberation”. But as soon as we buy one item, a cognitive shift to “implementation” occurs. “Our mindset changes from whether or not I should buy something to how do I buy this?” says Professor Ravi Dhar of the Yale School of Management, New Haven, Connecticut.

“If you want to resist the impulse,” says Professor Dhar, “ask yourself what else you could do with the money.” His studies show that people typically neglect to think of opportunity costs, or alternative things we could buy with the same amount of money. Those who do are more likely to choose the cheaper option or buy nothing at all.

Conversely, retailers can use framing techniques to get people to spend more. “Paying a lot for cashmere socks seems gross to many people,” says Professor Dhar. If cashmere socks are presented among other types of socks, we’re inclined to see them as socks first and consider their material second. But experiments have shown that if the same socks are presented alongside other cashmere goods, we categorise them as “cashmere” first and “socks” second, and we’re willing to spend more.

There’s another framing technique to increase spending. When buying a new backpack, for example, our tendency for “duration neglect” means we don’t typically think about how long we’re going to use it for. But if people are asked to consider how long an item is meant to last, they’re likely to pay more.

The pain of paying and what it depends on

Such framing techniques influence our pain threshold for paying. People are, generally speaking, loss averse and the idea of a “pain of paying” was coined some two decades ago by professors Drazen Prelec of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and George Loewenstein of Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Think of sitting in a taxi, staring at the meter creep higher and higher. It’s painful.

But what kind of a pain is it exactly? A brain imaging study led by Professor Nina Mazar, a behavioural scientist at Boston University, found that the pain of paying is not like a physical pain. It’s more similar to distress or anxiety on a neural level; it can help keep our spending in check.

However, not all payments are equally painful. Research tends to revolve around three key factors. The first is payment method. Paying by card is less visceral and therefore easier than paying with cash. In one study, people were willing to pay twice as much to bid on tickets for a basketball game if they could pay by credit card rather than in cash. Contactless payments and phone payments make parting with money even easier.

The latest example of separating purchasing from paying are checkout-less Amazon Go shops, where people don’t consciously pay at all. Hundreds of cameras around the store are able to detect what customers take off the shelves and automatically charge their Amazon account when they leave.

Tightwads and spendthrifts

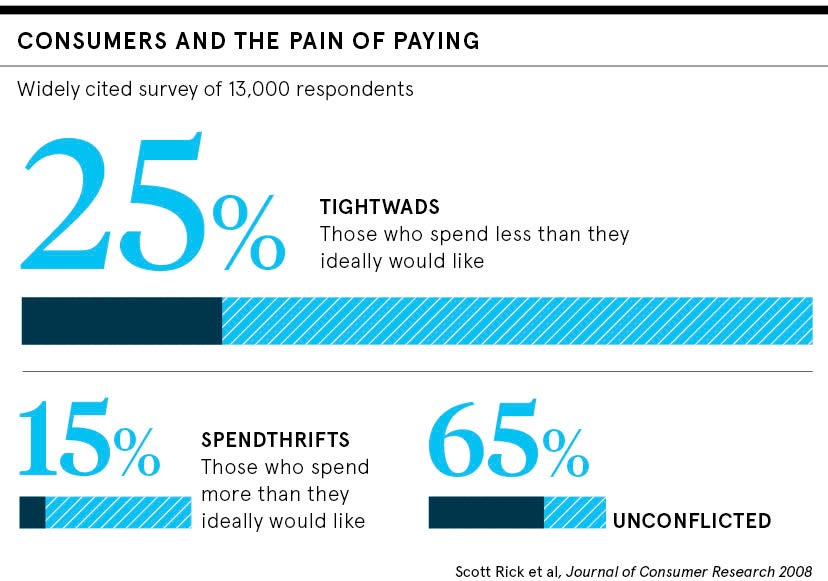

The second factor is our disposition. People who are tightwads and who make up about 25 per cent of the population, according to one study, experience more pain when it comes to paying than spendthrifts who make up 15 per cent

“Tightwads experience a lot of distress when they make purchases, especially the optional kind, and that prevents them from spending the money they think they should spend on certain things, and they sometimes kick themselves afterwards,” says Scott Rick, associate professor of marketing at the University of Michigan.

On the other side of the spectrum, spendthrifts hardly experience any pain at all. “They just can’t stop themselves,” says Dr Rick. Spendthrifts are largely insensitive to payment methods, but for tightwads, contactless methods and framing techniques, for example if a fee is described as “small”, make a difference.

Virtue and vice products

The third factor is whether we consider a product virtuous or frivolous. Buying fat-free yogurt feels different from buying ice cream with sprinkles. Only the latter gives us pangs of guilt.

Virtuous items are those we consider necessary and they’re more likely to induce shopping momentum than vice items, which make us pause because of the momentary guilt. So, buying milk leads to more subsequent purchases than buying ice cream.

But there’s an effective way for companies to counter the guilt we feel when buying “vice” products. It’s an age-old method: coupling vice products with charitable donations. In one study, 48 per cent of people were likely to opt into a donation when buying theme park tickets, but only 32 per cent did so when buying a six-month supply of toothpaste.

So, if a vice product is coupled with a charitable donation, people’s guilt is balanced by the warm glow we experience when we give to charity and the moral satisfaction we purchase. Our pain of paying is assuaged, while both the company and charity benefit.

Shopping momentum and framing techniques

The pain of paying and what it depends on